Fear transcends mere emotion; it is the unspoken vernacular of the soul. Listening to and understanding the fears we hold, both individually and as a nation, may grant us a deeper understanding of human nature, of what truly matters in life, and of our path to growth. It is very much like gazing into a mirror that, despite skewered reflections, invariably reveals an authentic fragment of ourselves. This fear is neither a mere physiological response nor a fleeting passion: think of it as a clandestine key, one that can unlatch concealed doorways in the soul, thereby laying bare crucial aspects of our humanity. That modern Vietnamese art may lack depictions of savage and terrifying lions does not imply a lack of gruesome, intense figures in traditional artistic expressions. Certainly, lions, tigers, and leopards inspire dread, but that is a primal, biological fear. For the Vietnamese, there exists a more profound, spiritual trepidation – one that, in the world of spirits, surely takes the form of malevolent entities and spectres. In this article, we propose a discussion of the design termed “ho phu” – a motif only tangentially related to great cats, yet is concurrently the most dreadful and adored design in Vietnamese art.

“[Ho phu] – a motif only tangentially related to great cats, yet is concurrently the most dreadful and adored design in Vietnamese art. “

Apprehension when faced with the force and menace of nature’s great predators can, eventually, foster a sense of awe and worship. Early mankind had a clear sense of their limitations before creatures boasting superior powers, extraordinary agility, or formidable natural armaments. In many ancient cultures worldwide, animals such as tiger, lion, leopard, bear, snake and eagle, inter alia, were afforded a distinctive role within their belief systems and mythos.

This sense of inadequacy could, in turn, cultivate respect, with these animals seen as manifestations of nature’s irresistible powers. The veneration of certain formidable creatures associated with food supplies or other essentials of communal life could represent an attempt to gain divine favours, to prevent incurring their displeasure, or to safeguard the availability of vital resources. Likewise, predatory animals frequently bearing distinctive features thus act as representations of high virtues, including power, valour, nimbleness, or hunting skills. The act of holding them in high esteem could be seen as an attempt to establish a link with these ethereal energies. With the passage of time, narratives and folklore about these ferocious creatures would often be expanded, assigning to them otherworldly powers or important functions in the communal understanding of the universe. Worship was commonly demonstrated by means of rituals, pictorial representations, revered statues, or taboo practices concerning these beasts. These observances solidified the sacred link forged between mankind and the animal kingdom. In Vietnam, the indigenous tiger ranks amongst the most savage in the kingdom of beasts, earning it the title “Lord of the jungle”.

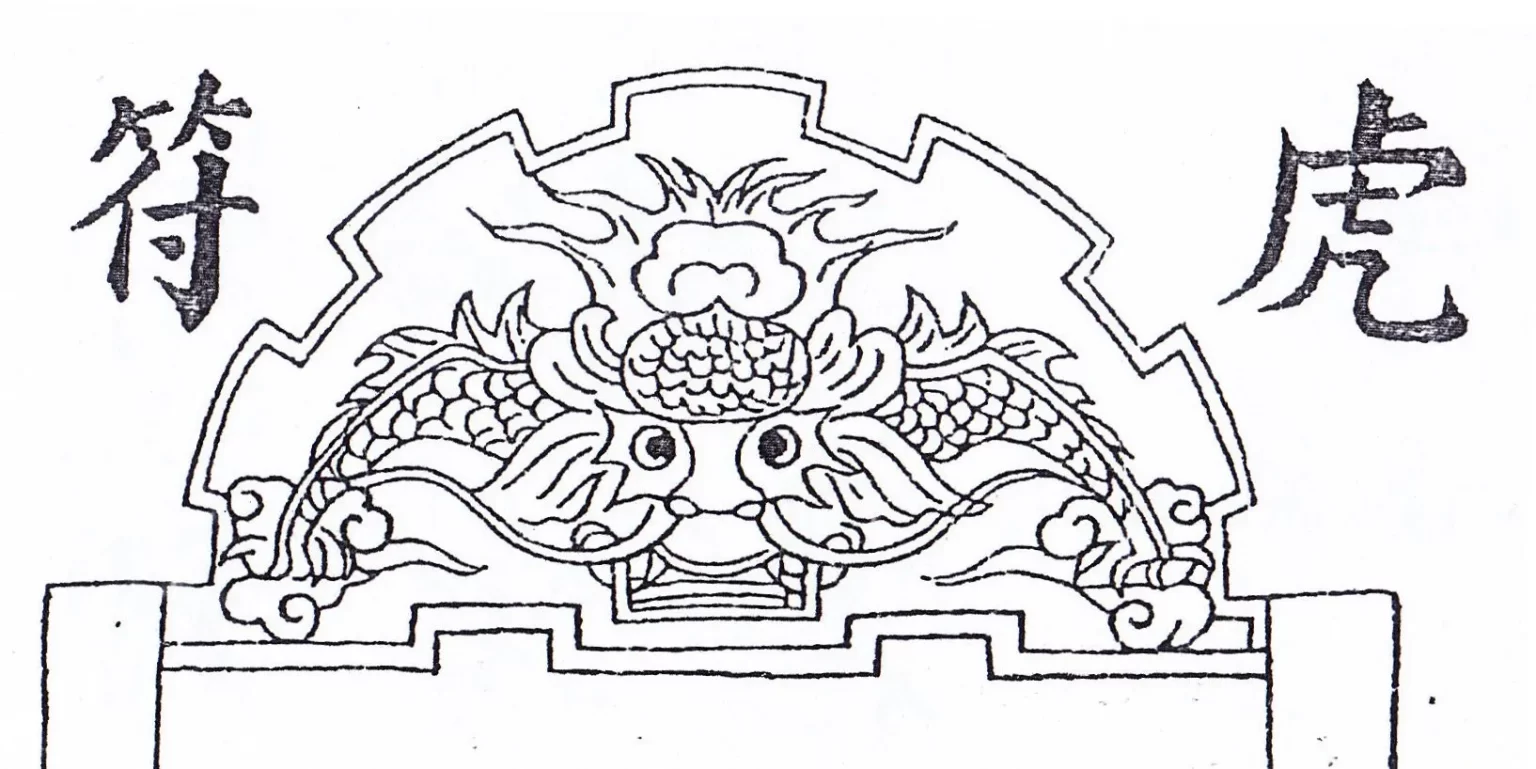

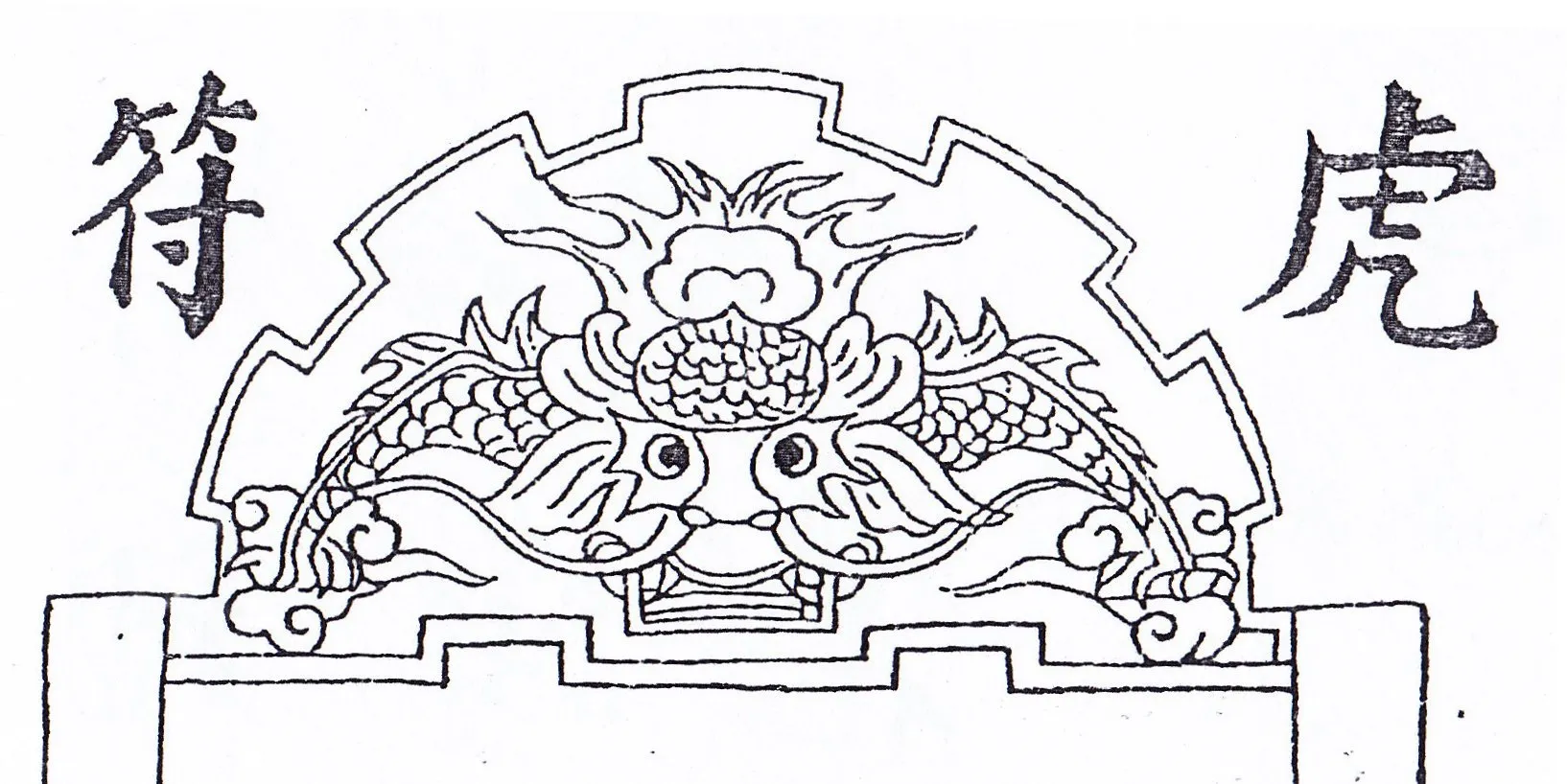

Within his scholarly treatise on the material civilisation of the Vietnamese, French academic Henri Oger copied a depiction of a gate bearing the inscription “ho phu” (虎符). This appellation, stemming from folk parlance, thereby first made its way into scholarly circles, and over the past one hundred years, this designation has led to unfortunate confusions. Consequent to this system of naming, the majority of studies on Vietnamese art, religion and symbology has, for a considerable time, generally applied the Sino-Vietnamese phonetic renderings of the term “ho phu” or “La Hau” (羅睺) to the motifs of Kala and Rahu, despite their Indian origins. The roots of this particular naming convention lie deep within the visual tradition of tiger and leopard heads on Chinese armour. Furthermore, Chinese architecture also presents the “be ngan” (狴犴) design, a common feature in the embellishment of prisons, especially those intended for particularly dangerous criminals. The “be ngan”, dragon-headed and tiger-bodied, is amongst the dragon’s nine scions, though its dam was a white tigress. In the military history of feudal China, there existed a form of tiger-motif military token, referred to as the “ho phu”. This “ho phu” functioned as a military pass endowed by the Chinese Emperor to his commanders to direct soldiers. Taking the complete shape of a tiger, it was typically cast in bronze or gold and divided into two. An order was only deemed authentic and actionable when both halves were united, thus depicting an entire tiger. The term “phu hop” (符合, “to accord”, “to match” or “tally”) has its etymological basis from this practice. “The Complete Annals of Dai Viet” records that in the eleventh month of the Fire Goat year (1427 in Gregorian calendar), Emperor Le Loi returned the tiger tally belonging to Lieu Thang, the Marquis of An Vien, to the Ming court.

The Puranas, amongst the most ancient sacred texts, provide a comprehensive portrayal of Rahu and Ketu. It is told that as the devas (heavenly beings) were churning the ocean of milk for the elixir of immortality, the fiend Rahu insinuated himself into their midst, intent on surreptitiously imbibing this holy nectar. The Sun and Moon, espying his subterfuge, wasted no time in apprising Lord Vishnu of the matter, whose anger was kindled instantly, decapitating Rahu by means of the Sudarshana Chakra. However, as Rahu had already taken the amrita (immortality elixir) into his mouth, he did not perish, although a portion of his form was gone. From that day onwards, Rahu bore an undying grudge against the Sun and the Moon. Thus, from time to time, he engulfs them, causing solar and lunar eclipses. However, having lost his torso, he is unable to contain the Sun nor the Moon. Consequently, after a short while, the celestial bodies emerge once more.2

According to John Dowson (1870), Rahu’s form was that of a monster with a dragon’s head, four arms, and a tail. Once his body had been cut off, he is characteristically portrayed as a dragon head with two arms, the surviving portion after Vishnu’s divine rage.3 Huynh Thi Duoc offers the following depiction of Rahu’s dragon head: Rahu – the asura (anti-god) of solar and lunar eclipses. Rahu is a key figure in astrology, progressively personified as an asura, identified as the agent behind solar and lunar eclipses and the force directing meteors. This asura is rendered as a monstrous figure that, at intervals, devours the sun and moon, thereby engendering eclipses. Rahu presents with a dragon head and a comet-like tail.4

Such narratives explain why the physical form of Rahu, also called “Ria hu” in Soc Trang (Vietnam), comprises merely a head and two fore-appendages. As a figure of dual significance, Rahu is, first and foremost, connected with trickery, covetousness and fury. Yet, having partaken of the elixir of immortality, he is also celebrated as a bestower of good luck, fame, authority, power, affluence and ultimate knowledge. In Thai Buddhist tradition, Phra Rahu is worshipped as a preternatural force that eradicates malevolence and defends the Dharma. This belief finds its basis in a Pali sutta which narrates how, when Rahu attacked Chandra (the Moon deity) and Suriya (the Sun deity), the Buddha appeared and compelled Rahu to release them.

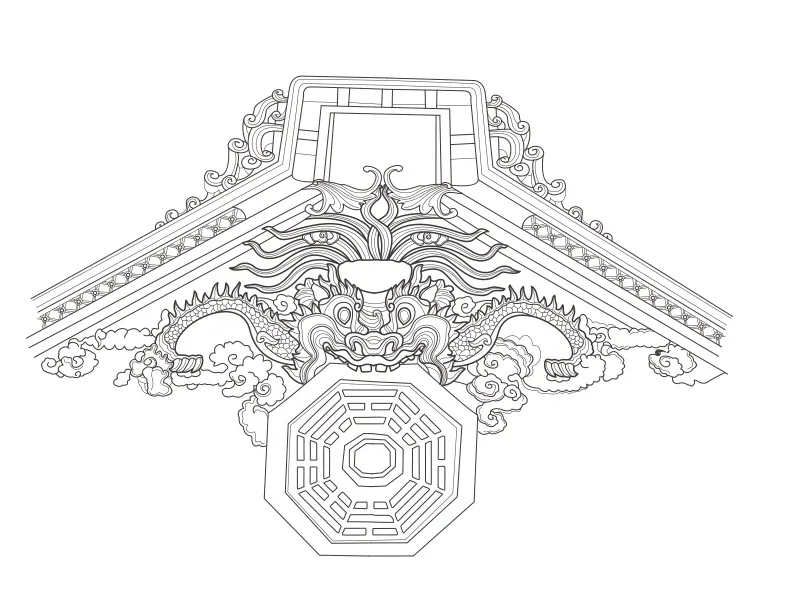

The Vietnamese portrayal of Rahu, distinguished by the ”long ham tho” (龍銜壽, “dragon holding longevity”) element, is a distinct Vietnamese creation. It must first be asserted that neither Chinese, Japanese, nor Korean art features such a design of a demi-dragon holding the longevity character; instead, they solely depict full-bodied dragons interacting with this symbol. In the art of Champa, the figure of Rahu is not prevalent, and this particular configuration is also absent. The inclusion of the longevity symbol, depicted as being partially consumed by Rahu in Vietnamese art, stems from his fabled attainment of immortality through drinking the divine elixir.

“The Vietnamese portrayal of Rahu, distinguished by the ”long ham tho” (龍銜壽, “dragon holding longevity”) element, is a distinct Vietnamese creation.”

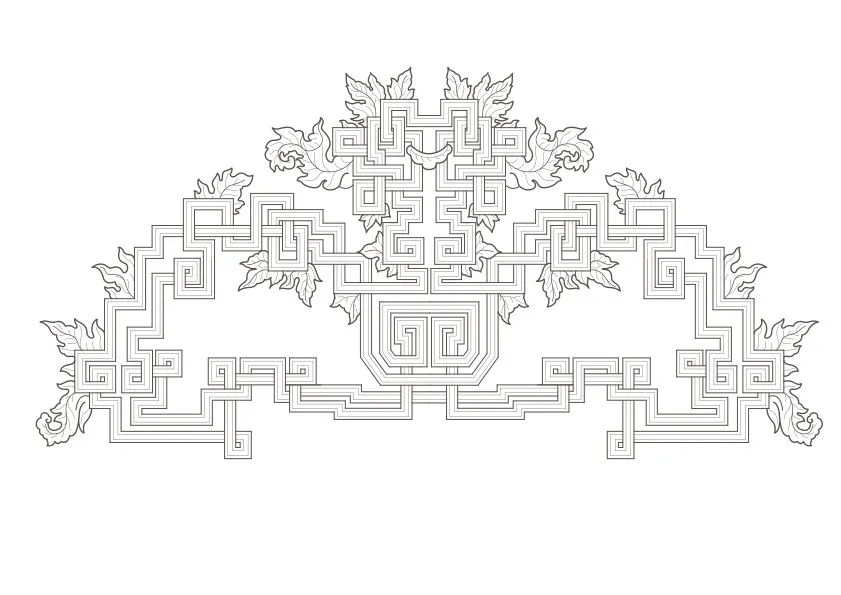

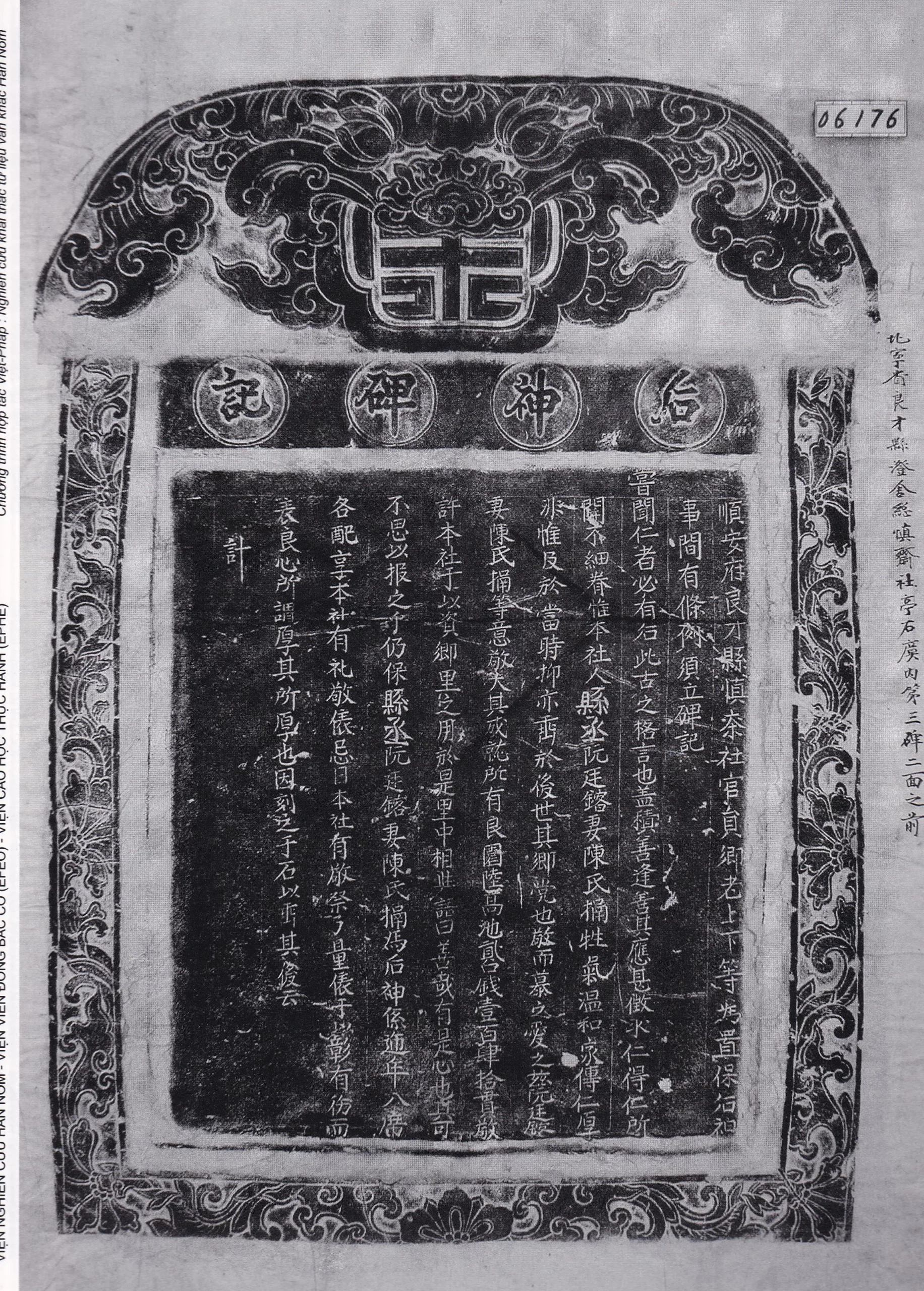

The Rahu design, under the appellation “long ham tho”, was formally incorporated into courtly art, finding common application on the crests of stelae and the gable ends of edifices such as Thai Hoa Palace and Ngung Hy Palace. A paradoxical situation exists whereby, despite the Rahu design’s extensive application across the country, prevalent from North to South, the questions of its nomenclature, origins and symbolic import were seldom subjected to comprehensive debate. Priest L. Cadiere (1869–1955) was probably the first to offer an exegesis of this design. He discerned no relation to the tiger symbolism, yet neither did he uncover any demonstrable link to Indian culture. One of the most singular adaptations of the Rahu design during the Nguyen dynasty involved its transformation into a lotus – occasionally a single bloom, at other times a multi-flowered cluster. Thus, a design considered amongst the most baleful in Vietnamese art was artistically rendered into something of a phantasmal beauty. The Kim Lien Temple, one of Thang Long’s four guardian citadels, exhibits this lotusified Rahu. This remarkable transformation further graces the armour of the Dharmapala figures, achieving a kind of spectral elegance, a quality rarely paralleled in Chinese fine arts. Whilst art under the Nguyen dynasty is frequently perceived as bearing strong Chinese influences, the Rahu design constitutes a remarkable exception to this tendency. Its presence was pervasive, extending from the southernmost to the northernmost, embellishing a diverse range of structures from communal houses, pagodas, temples to mausoleums, palatial edifices and imperial residences. It was featured on ritual objects as well as in architectural ornamentation, crafted from terracotta and ceramics to wood, earthenware, even fabrics and silks. Alongside the “Nghe” (猊), Rahu stands as one of the most unique and most challenging-to-interpret sacred creatures of the Vietnamese.

A highly resonant and distinctive folk expression, “five fathers and three mothers”, speaks to the complex nature of ancestry, most notably within the specific cultural milieu of Vietnam. Poised at a geographical nexus where major civilisations (China and those of Southeast Asia) converge, Vietnam has adeptly received, sifted and integrated various cultural values to cultivate its own distinctive identity. Each of these – conflicts, migrations, cross-cultural marriages and more – has added to the formation of complex strata of heritage for individuals and the community at large. Writing in “Engaging with art” (Fine Arts Institute, 1998), Thai Ba Van noted, “Our nation of Vietnam, past and present, has always been fortunate and proud to be situated on the thoroughfare of diverse civilisations. History affirms that this was no impediment that resulted in a mere mixture, but indeed a felicitous geographical circumstance, enabling our Vietnam to be yet more itself.” Through examining the cultural origins of the “La Hau” – “ho phu” design, we perceive how these overlapping and intermingled cultural strata have endowed Vietnam with its greater captivation and the multifaceted splendour today.

Words: Trần Hậu Yên Thế

Translator: Hương Trà