As a field that combines science and art, botanical art once played an important role in both Vietnamese painting and medicine. In the twentieth century, botanical art was popular in textbooks, scientific publications, advertisements, etc. However, it has gradually declined since the 2000s due to the widespread use of digital cameras. In this article, I ask the following questions: What is botanical art? How has it developed? In comparison to the global development of botanical art, what is unique in its history in Vietnam? What are the current challenges and opportunities in this field?

“Botanical art” always goes alongside “botany”, the study of plants. Each botanical artwork results from close collaboration between botanists and artists, where science and art complement one another. These works are displayed in various settings, such as art exhibitions, natural history museums, botanical gardens, and research institutions. To gain a better understanding of the history of botanical art, we must first consider the development of both botany and art throughout human history.

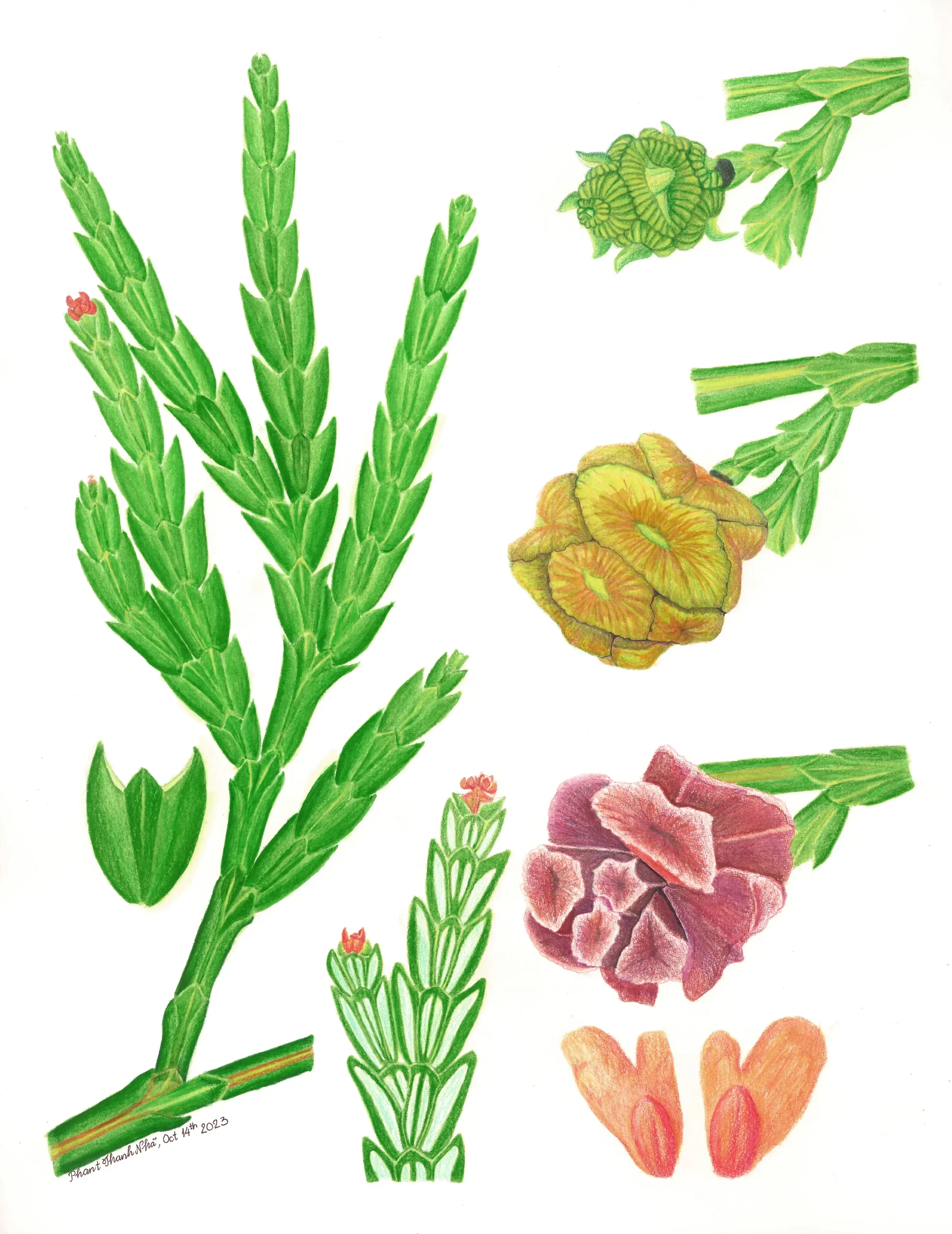

Each region has its own specific climate, terrain, soil, and ecosystem. In French caves, for instance, prehistoric paintings depict scenes of daily life and the typical flora and fauna of cold climates. Since ancient times, as our ancestors foraged in nature, they needed to distinguish between edible, medicinal, and poisonous plants. This knowledge was passed down through generations and laid the foundation for the establishment of botany, one of the oldest sciences in human history. The earliest recognised works in botany are “Enquiry into Plants (De Historia Plantarum libri decem)” and “On the Causes of Plants (De Causis Plantarum)” by Theophrastus, an ancient Greek philosopher, botanist, and scientist. These works were written between circa 350 BC and circa 287 BC. The early development of botany was closely connected to medicine, with the first Western botanical illustrations primarily focused on medicinal herbs. The oldest recorded medical text is “On Medical Material (De Materia Medica)” by Pedanius Dioscorides, an ancient Greek physician and pharmacologist, written in the first century CE. The book lists about 600 plant species, along with various medicinal minerals and animals. Translations of “De Materia Medica” into other languages were often supplemented with detailed illustrations of medicinal herbs.

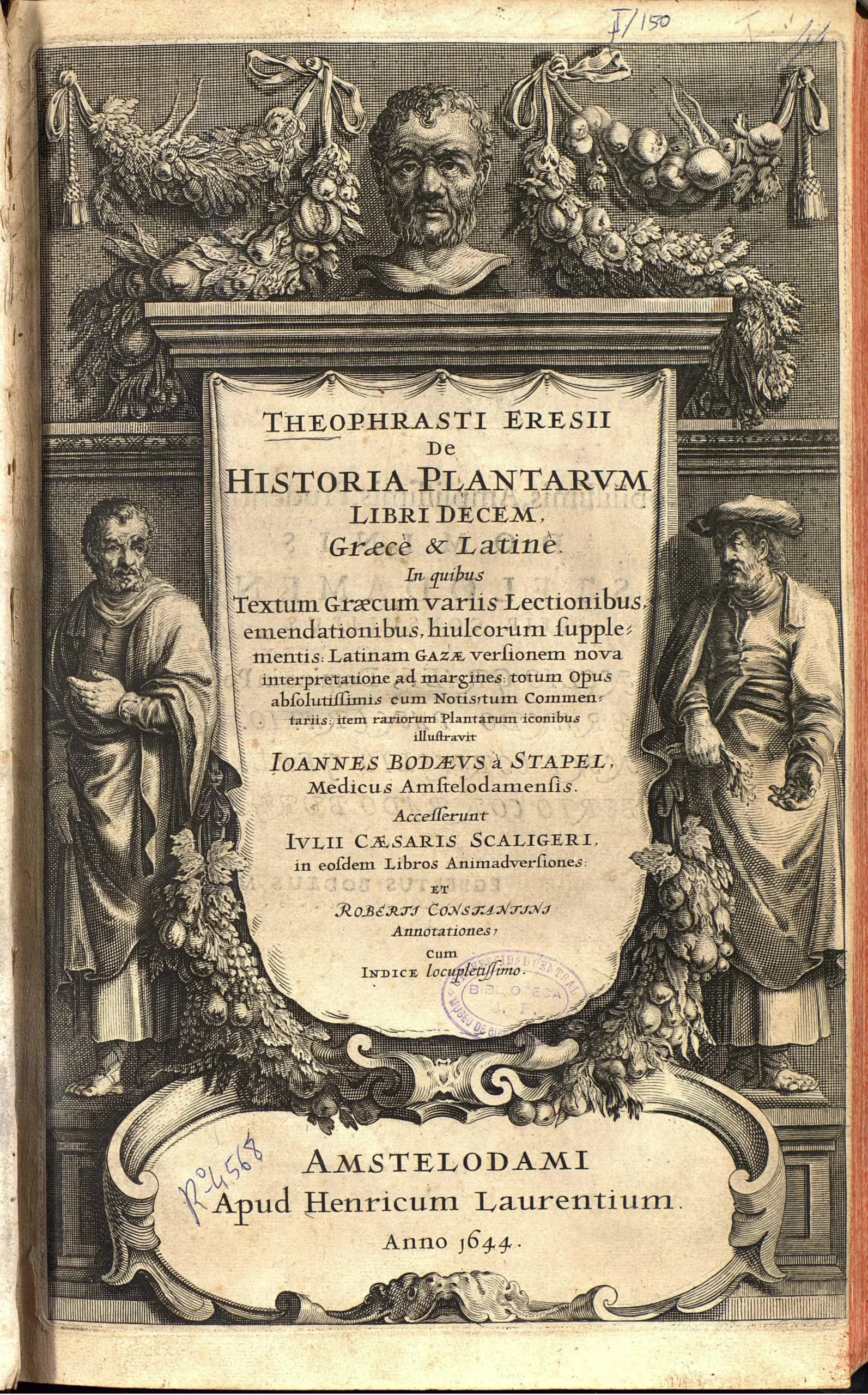

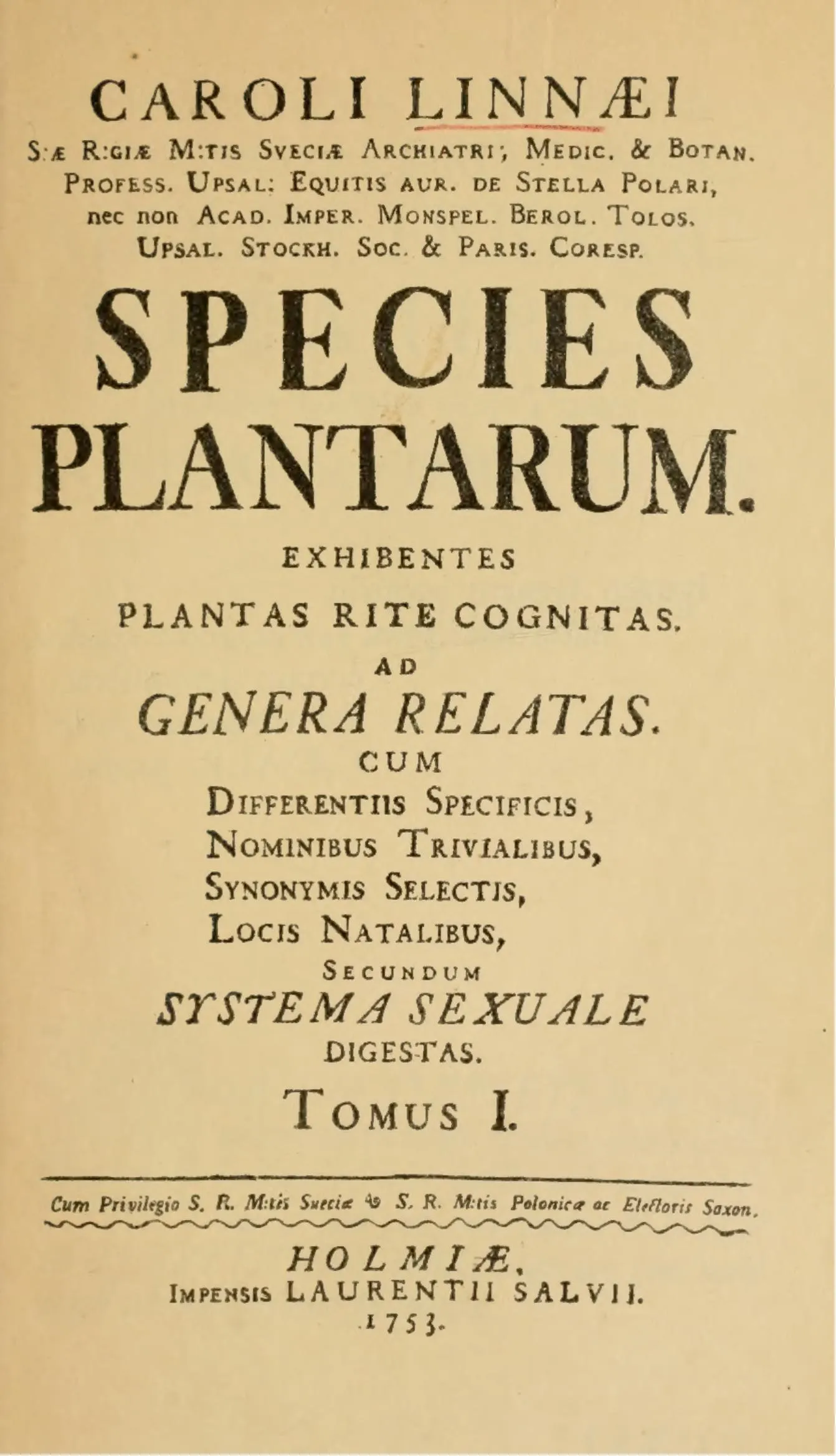

In the early fifteenth century, artists began accompanying scientists on expeditions to unexplored regions. They often worked in pairs – while the scientist documented their study of specimens in writing, the artist observed and visually recorded plants and flowers through drawings. Two classic works marked an important turning point in the development of natural science, particularly in botany: “The Species of Plants (Species Plantarum)” (1753) by Carl Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy, and “On the Origin of Species” (1859) by Charles Darwin. The flourishing development of botany ushered in the golden age of scientific illustration and botanical art.

In the East, many ancient Chinese pharmacopoeias documented medicinal herbs from the southern regions, such as patchouli, wild ginger, areca catechu, betel, malva nut, cantaloupe, etc. Vietnamese traditional remedies and methods for the processing of medicinal herbs were also recorded in these pharmacopeias. For instance, in the book “Compendium of Materia Medica (本草纲目)” in the Ming Dynasty (published in 1596), Li Shizhen praised the Vietnamese methods for the processing of deer antler glue and dried Chinese yam. This highlights the contribution of Southern medicinal herbs and herbal remedies to the development of Oriental medicine. In “The Ancient Graphic Arts of Vietnam” (2011), Phan Cam Thuong, Le Quoc Viet, and Cung Khac Luoc noted: “Poetry was primarily transmitted orally. Scientific books were almost nonexistent. Medical and geographical books were mainly esoteric and not widely disseminated… During Chinese rule in Vietnam from 111 BCE to the 10th century, no printed relics were found…”. In the wood carvings preserved in the pagodas of the Dau – Keo region, Thuan Thanh, Bac Ninh, plant imagery primarily serves decorative purposes.

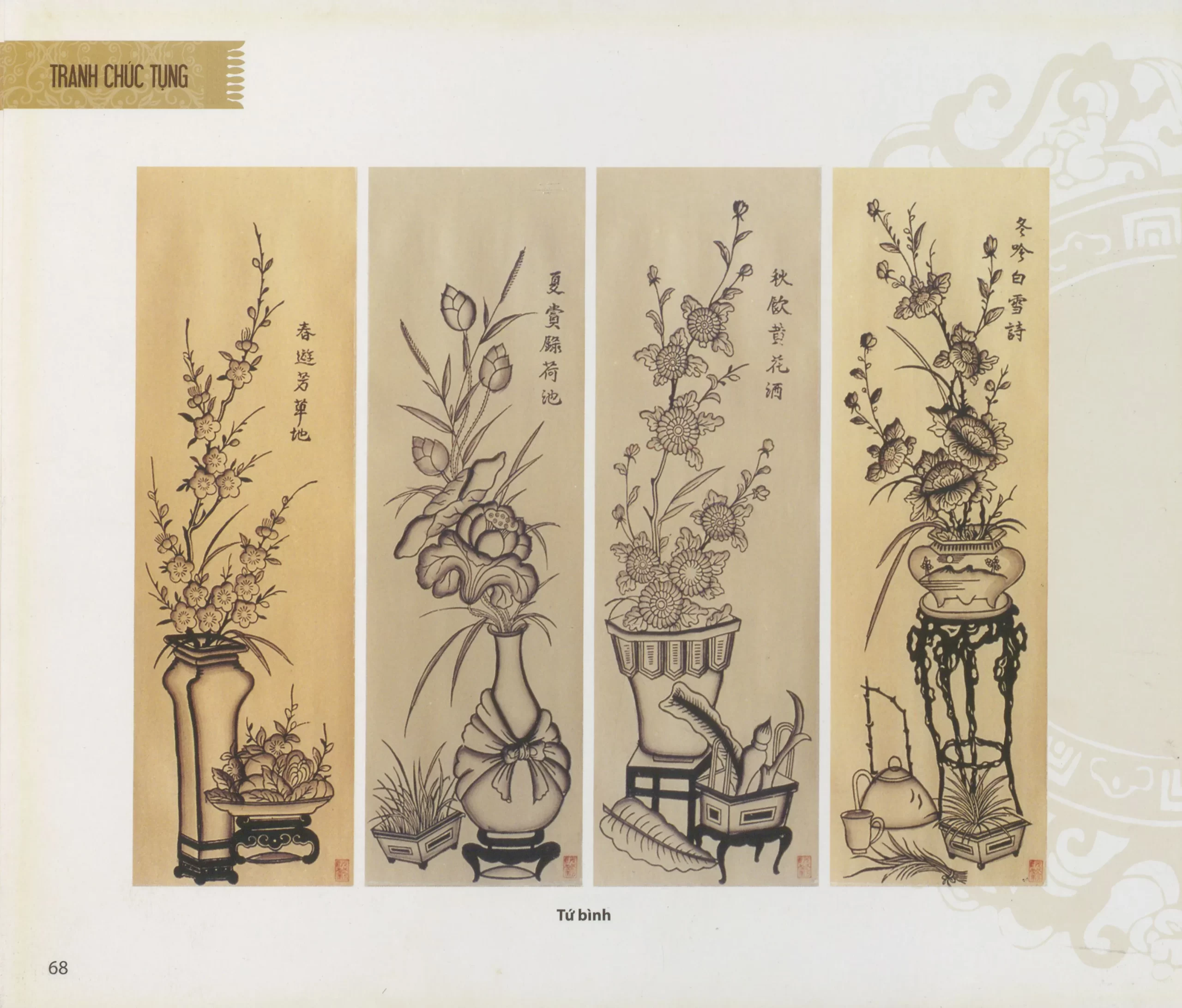

During the feudal period from the Ly to the Nguyen dynasties (939–1945), the study and depiction of plants focused mainly on medicinal herbs. The medical books of Tue Tinh (fourteenth century), Phan Phu Tien (fifteenth century), and Hai Thuong Lan Ong Le Huu Trac (1724–1791) were all based on Southern medicinal herbs, laying the foundation for traditional Vietnamese medicine. In “The Miraculous Effectiveness of Southern Medicines” (fourteenth century), Tue Tinh described herbal medicines and methods for using plants to treat common illnesses of ancient Vietnamese people, such as using ginger, galangal, and Kaong Palm to prevent and cure illnesses. Ancient Vietnamese people also drank Daly River Satinashl tea to aid digestion and lower blood sugar or chewed betel with areca nut and lime to strengthen teeth and freshen breath. This indicates that the earliest botanical studies in Vietnam also began with medicinal herbs, much like the development of botany worldwide. These medical books mainly described plants in writing. In Dong Ho and Hang Trong, two traditional Vietnamese folk paintings, plants are vividly depicted. Images of lotus, apricot blossoms, parasol trees, pine trees, coconut trees, and others are not only aesthetically pleasing but also carry profound cultural and spiritual meanings. They symbolise the four seasons and the customs of Vietnamese people in daily life and during festivals.

The Flowers of Four Seasons paintings, part of the New Year greetings theme from Dong Ho folk paintings. Source: “The Craft of Dong Ho Folk Paintings: A Cultural Heritage of Vietnam” (2014) by Vu An Chuong and Nguyen Dang Che.

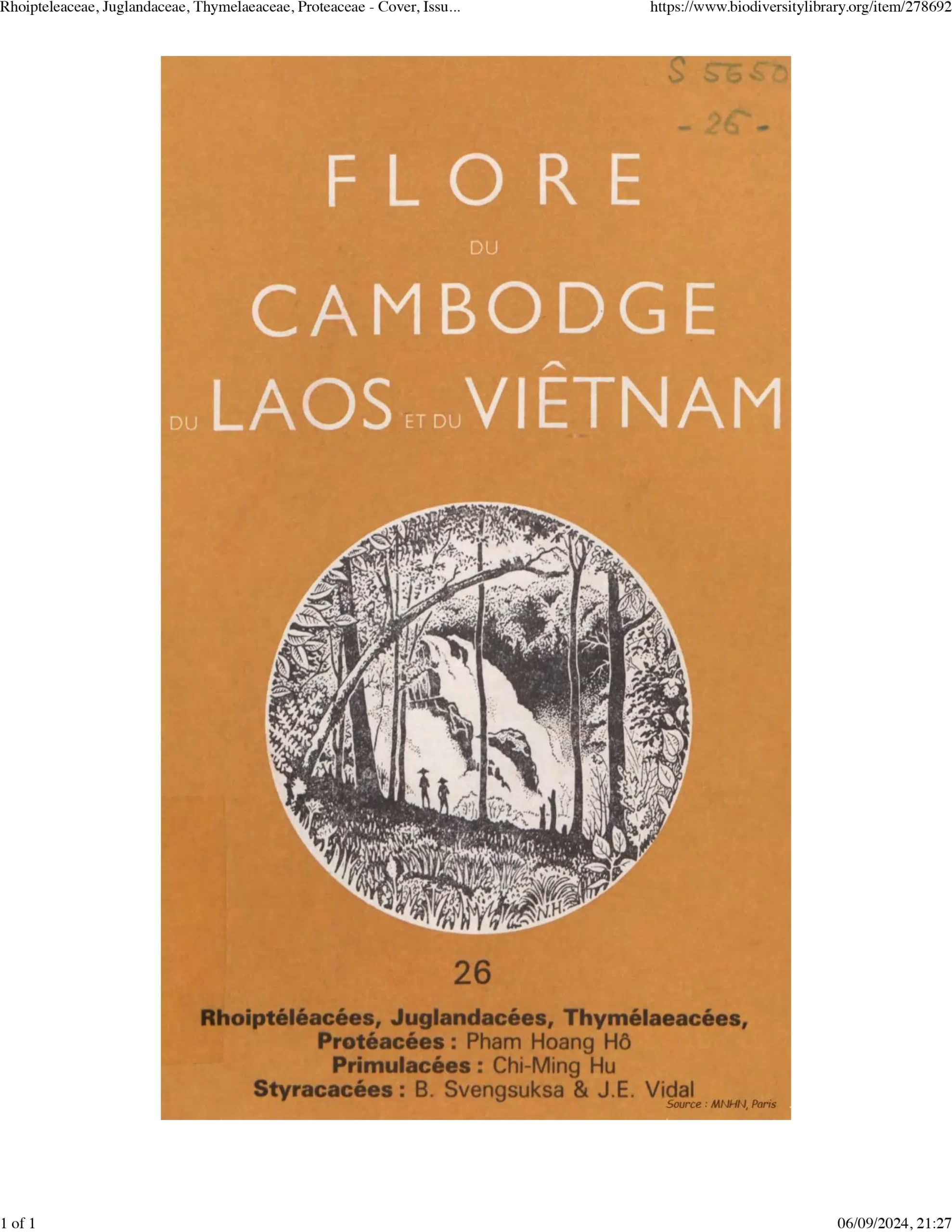

After becoming a French colony in 1858, the flora of the Indochinese Peninsula, including Vietnam, was extensively studied and published by French and Western naturalists. Notable works include “General Flora of Indochina (Flore générale de l’Indo-Chine)” by Lecomte, M.H., Humbert, H., and Gagnepain, F., with seven volumes published from 1907–1951; “Forest Flora of Cochinchina (Flore forestière de la Cochinchine)” by Pierre, L., with four volumes published from 1880–1907; and the series “Flora of Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam (Flore du Cambodge, du Laos et du Viêt-nam)”, with 35 volumes published from the 1960s by the National Museum of Natural History in Paris. Among them, “Flore générale de l’Indo-Chine” is the most outstanding one, providing detailed descriptions of thousands of plant species, their distribution, and their habitats. This work not only offers valuable information about the process of discovering plants in Indochina during the French colonial period, but is also considered an important historical document. The illustrations are highly regarded by botanical illustrators for their scientific accuracy, clear composition, and masterful brushwork.

During the French colonial period (1858–1945), Vietnam underwent profound changes in the fields of politics, culture, education, science, and fine arts. The establishment of the Fine Arts School of Indochina in 1924 marked the beginning of modern Vietnamese fine arts. Besides introducing Western techniques and styles, the school helped Vietnamese artists and students engage with modern art. In the field of natural sciences, many young Vietnamese intellectuals went to the West to study and return to serve their homeland, notably the late Professor Pham Hoang Ho.

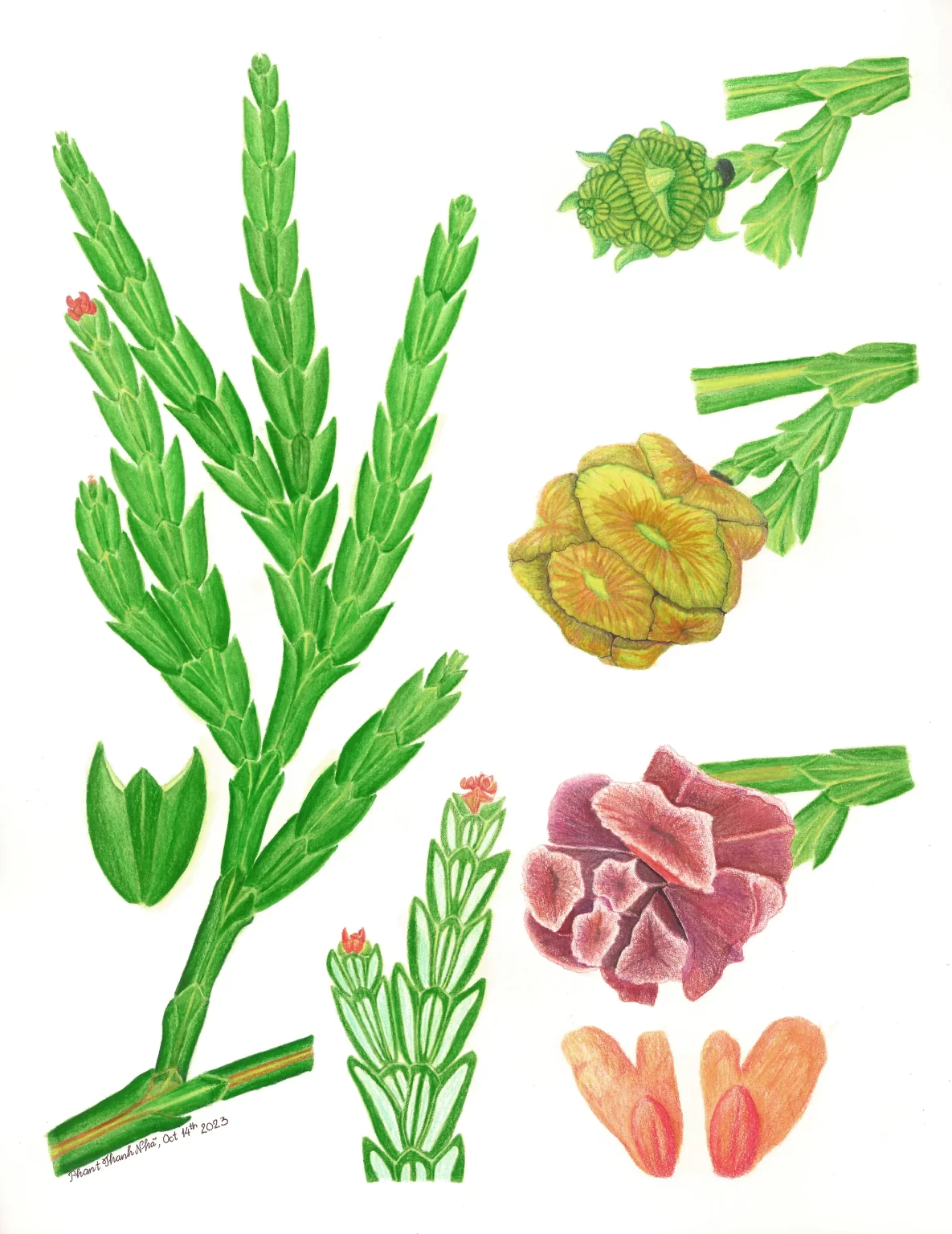

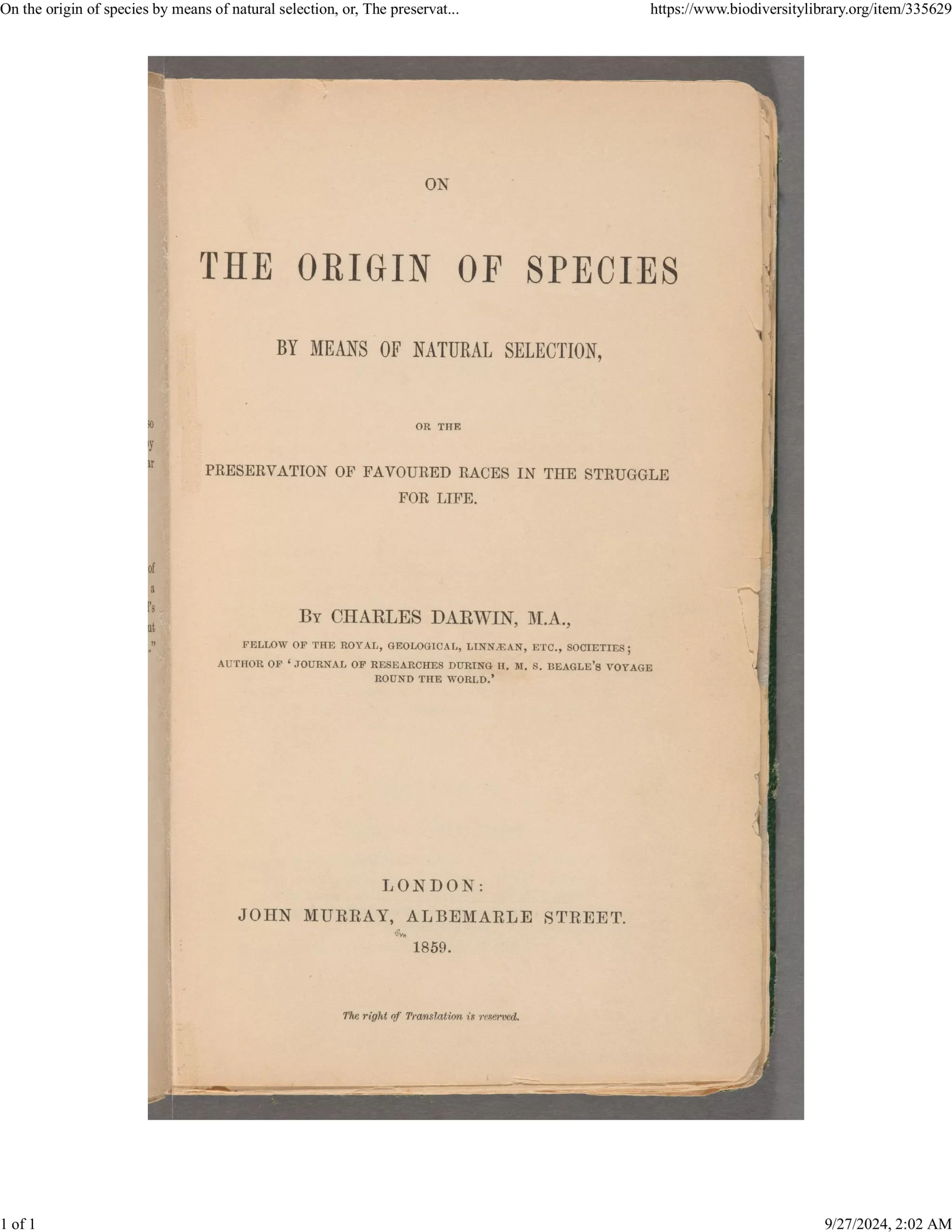

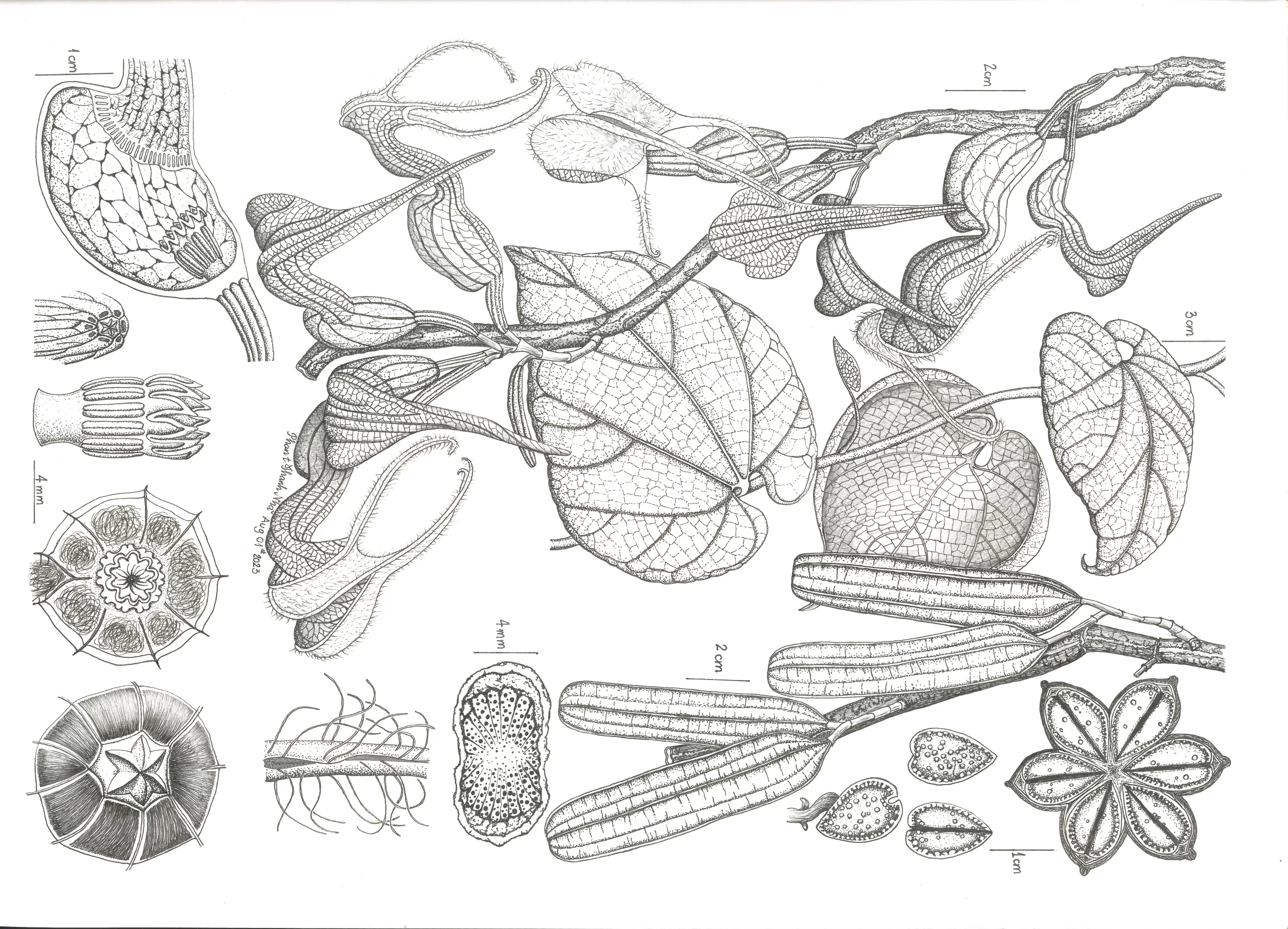

Professor Pham Hoang Ho returned to Vietnam and was appointed Director of the Nha Trang Institute of Oceanography, the predecessor of the institute today. In addition to teaching, he conducted numerous field surveys to research and collect specimens. In 1960, he published “Plants of South Vietnam”, the first study of Vietnamese flora by a Vietnamese person. In his works, Professor Pham Hoang Ho illustrated plant species, seaweeds, cells, and more, significantly contributing to the integration and development of Vietnamese botany and botanical art within global trends. To share knowledge about biology and botany, he used fine-tip pens to illustrate on paper, combined with concise and succinct writing to optimise page space.

After multiple additions and revisions, in 1999, Professor Pham Hoang Ho completed his three-volume work “An Illustrated Flora of Vietnam”. This work is the first comprehensive study on Vietnamese flora conducted by a Vietnamese scientist. These book series provided detailed information about each plant species, including scientific names, common names, synonyms, names in various languages, and brief yet comprehensive descriptions of each species’

At the end of the twentieth century, the advent and rapid development of digital cameras made it possible to capture sharp photos quickly, posing new challenges for botanical art and scientific illustration of plants. In the past, when publishing new plant species, reputable scientific journals often required an accompanying black-and-white scientific illustration. However, to shorten time and reduce costs, photographs gradually became more favored and widely accepted. Despite this shift, scientific illustrations and botanical art still maintain unique advantages and a distinct position that photographs cannot replace. One of the key strengths of illustration is that the artist’s drawing is not affected by external factors, such as lighting or environmental conditions, which can often diminish the quality of photographs. Moreover, plant specimens can be easily damaged during collection and storage, leading to issues like lost petals, insect damage, or crushing. In such cases, botanical artists could recreate the specimens in their finest form on paper – something a camera cannot achieve.

With the rapid development of technology and artificial intelligence (AI), botanical art and scientific illustration are facing unprecedented challenges. With the support of botanical gardens and research institutes, Society of Botanical Artists and various national botanical art societies have been established. There has been a rise in global botanical art exhibitions, training courses for botanical artists and illustrators, and the publication of exhibition catalogs to promote and celebrate this unique art form that bridges science and art. In Southeast Asia, recent years have seen the founding of the Indonesian Society of Botanical Artists (IDSBA), the Philippine Botanical Art Society (PhilBAS), the Botanical Art Society Singapore (BASS), and the Thai Botanical Artists Society (THBA). On 15 November 2022, these societies jointly opened the exhibition “Flora of Southeast Asia” in Singapore. At the Botanical Art Gallery in the Inverturret Building (Gallop Extension) and other venues across the Singapore Botanic Gardens, the exhibition showcased more than 120 botanical artworks by 85 artists from Singapore, Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam, India, UK, USA, Japan, Denmark, the UAE, and Canada. The “Flora of Southeast Asia” exhibition is significant as it highlights the close collaboration between regional botanical art societies in their efforts to introduce and promote botanical art to the public.

Looking ahead, the botanical science and art community in Vietnam is optimistic about the establishment of a national botanical art society. The creation of such a society would not only advance the research and conservation of botanical art but also provide a strong platform for knowledge exchange and collaboration between local and international botanists and artists.

Words: Phan Thị Thanh Nhã

Translation: Lưu Bích Ngọc