High on the pine-clad hills of Chau Chu village (Hue), I accompanied uncle Nguyen Thuyen to visit the grave of sculptor Diem Phung Thi (1920–2002), interred beside her husband, with her mother’s grave resting on the next hill. That encounter with the groundskeeper lifted the veil on the private life of the artist – a humble and compassionate woman whose life mirrored her art.

AMONGST THE PINES, THE EPITAPHS

Under the sultry sun and gentle breeze of midday, uncle Thuyen diligently gathered fallen pine branches from the gravesite. “It’s the pine-shedding season.” He said with a profound understanding of nature, stemming from nearly three decades of picking up pine cones on those graves. I was grateful to meet him, the caretaker of Diem Phung Thi, her husband and her mother’s graves.

Uncle Thuyen recalled a spring day in 1995 when he first met Diem Phung Thi and assisted her in finding her mother’s grave. Her parents were both from the intellectual class: her father was Phung Duy Can, a native of Ha Tinh, who later came to Hue to serve as a mandarin in the Nguyen Imperial Court, marrying a gentle woman from Vy Da. Since her father oversaw the construction of the Khai Dinh Tomb on Chau Chu Mountain as a minister, the family had lived in this area for a time. At her age of five1, her mother passed away, and her grave was located in Chau Chu. This was once a crucial revolutionary base of Huong Thuy district (now Huong Thuy town) and Hue city during the wars against the French and the American. A bullet-ridden wilderness, rarely trod by the common folk, saw its graves slowly fall into ruin. “When I found her mother’s grave, it was just a remnant…”, uncle Thuyen reminisced wistfully. Thereafter Diem Phung Thi had entrusted him with the restoration of her mother’s grave.

His house is on this side of the road, within the boundaries of Kim Son village, while Chau Chu village lies on the other side. A short walk up the hill will lead you to the resting place of the sculptress Diem Phung Thi and her husband, as well as her mother.

The burial site of the couple is located on a fairly high terrain, occupying an area of about one hundred square meters, with a monument foundation and a layer of scattered stones inside. The centrerpiece are twin graves of reddish-brown laterite. In 1997, following her husband’s funeral, she embarked on a journey to Quang Ngai to procure this unique stone. She carefully shaped it while it was still soft underground, then transported it to Hue to be carved into classical modules and installed as the twins.

Her husband rests on the right, his gravestone inscribed with: “In memorial of Dentist/ Nguyen Phuoc Buu Diem/ Loving wife: Phung Thi Cuc/ as Diem Phung Thi/ 1997”, to the left lies the final resting place of “Sculptress/ Diem Phung Thi”.

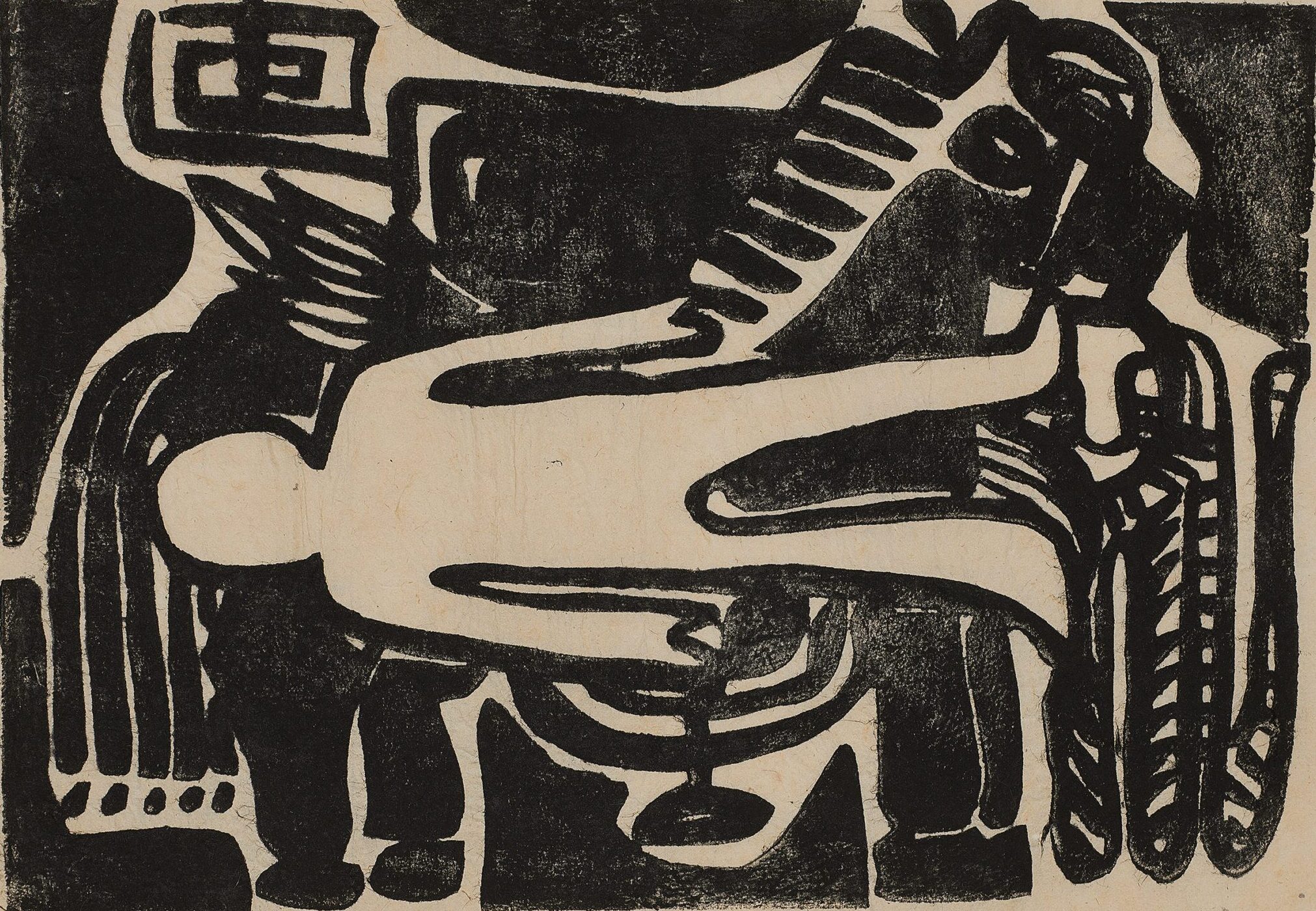

The centerpiece lies at the apex of her final resting place: a laterite sculpture positioned centrally on the rear platform of the grave. This pure work of art, in contrast to the more commercial aspects of the front part, transforms the entire site into a unified artistic statement, bearing the hallmark of the sculptress’s hand. The sculpture depicts a married couple, with the wife’s statue placed at a lower height than the husband’s, reflecting the traditional values that Diem Phung Thi held towards her husband. It reveals the multifaceted nature of Diem Phung Thi: a renowned artist and a devoted wife. To gaze upon this sculpture is to witness the harmonious integration of her creative self and her social identity, testifying to the consistent spirit she demonstrated both in her artistic creations and throughout her life.

Visitors to the cemetery have another opportunity to gain further insights into the depth of Diem Phung Thi at her mother’s grave – a more intimate and impactful memorial. Despite its smaller size, it comprises a cohesive and complete sculptural ensemble. The square plot features a circular structure composed of figures assembled from the artist’s classical modules. The mother’s statue, the tallest, is integrated with the form of an incense burner and surrounded by her children, creating a sense of intimacy, closeness, and reverence. The theme of maternal love is a recurring motif in Diem Phung Thi’s works, however this particular piece has a unique context and can be seen as a personal gift to the mother she had known for only five years of her life.

In an autobiographical passage, Diem Phung Thi recounts a memory of walking through a French street and encountering a deceased woman, curled up on the pavement, her hand clutching a newborn who was playing with a pacifier and the worms crawling out of the mother’s mouth. Her life was marked by such encounters, repeatedly witnessing the poignant spectacle of motherhood amidst adversity, separation, life, and death. The profound pain and haunting experiences piled up, reaching a peak during her sleepless nights in France as she watched television and pondered the fate of soldiers at war and their mothers. Confronted with such harsh realities, she transformed them into the material for sculpting her first human figures, imbued with a deep sense of love. She persevered through the duality: the witnessing in blood-soaked stream of life and the creating in art, driven by a desire for love.

EASTERN SOUL, WESTERN WAY OF BEING

Returning from the gravesite, uncle Thuyen and I sought solace in his home. We sat in the small living room, with an old TV, worn-out furniture, and a freshly poured cup of tea. Time flew by as I tried to capture fragments of the past, imagining Diem Phung Thi sitting in the same spot, chatting with uncle Thuyen dearly.

“What was Diem Phung Thi like during her lifetime?” I pondered. “Madam Diem was kind-hearted and simple. She loved wildflowers and would wear a cloth hat when going out, dressed casually. No one would recognise her as a great artist returning from Europe.”

This description is picturing the extraordinary modesty of her way of life. Diem Phung Thi trusted uncle Thuyen since she found in him a similar quality. In 1995, during the reconstruction of her mother’s grave, she had planned to find some masons to follow her sketched design, with uncle Thuyen overseeing the work. However, uncle Thuyen strongly advised against her intention. “I told Madam Diem that it wouldn’t do. She was a great artist who would pay attention to every detail. What if the workers didn’t understand her ideas?” Ultimately, she turned to Nguyen Hien, a faculty member of the Sculpture Department at the Hue University – University of Arts, to organize and supervise the construction. After that, she valued the simplicity of uncle Thuyen even more.

Diem Phung Thi had a deep, almost familial bond with uncle Thuyen. She often invited him to assist with some work at 1 Phan Boi Chau Street, Hue – a property gifted to her by the local government to serve as a residence for her and her husband at the time, as well as to establish a workshop and display her artworks (now the Diem Phung Thi Art Center at 17 Le Loi Street, Hue). “Sweeping the yard or mowing the lawn were easy for a laborer like me. It was just an excuse. The main reason was so I could have a full meal, take a break from farm work, and earn a little extra money.” His eyes lit up as he recounted a memory of Diem Phung Thi. Once at lunchtime, the housekeeper prepared a tray of food for uncle Thuyen to eat downstairs. Diem Phung Thi insisted that uncle Thuyen would have lunch with her and asked the housekeeper to prepare an extra serving for him, saying, “He works hard and has a big appetite.” Her kindness moved him deeply. Uncle Thuyên realized that beneath her simple and loving nature was a decisive, egalitarian, and Western way of life. He vividly remembers dining with the artist’s contemporaries, including writers Buu Y and Hoang Phu Ngoc Tuong, and Hue researcher Nguyen Dac Xuan. She treated everyone with warmth and equality, regardless of their social status.

On another occasion, when Diem Phung Thi heard that his eldest daughter had to drop out of school due to their financial situation, she was furious: “If you are able to have children, you shall provide them with proper education.” She then brought his daughter to her home at Phan Boi Chau Street and arranged for a tutor to come weekly to teach her reading and writing. Uncle Thuyen expressed his gratitude: “Even when she gave me a telling-off, I found joy in my heart, for I knew she was speaking the truth. She would only be so direct with someone she considered family.”

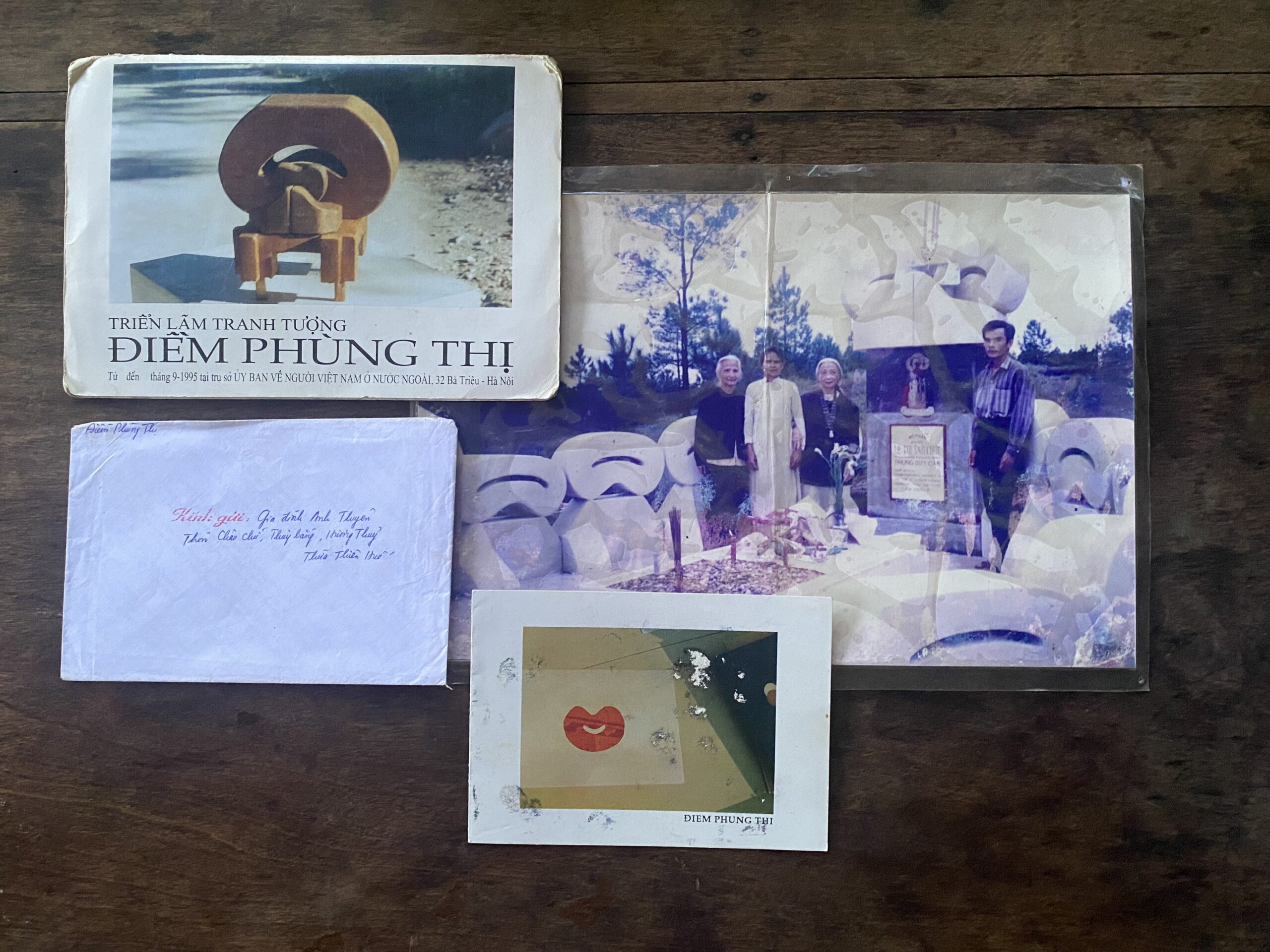

To look back, Diem Phung Thi had changed not only uncle Thuyen’s life but also that of his entire family. Sitting beside him in the living room, I handled the memorabilia he treasured: postcards and exhibition invitations from her. Among them was a precious photo taken at the inauguration ceremony of her mother’s grave after its reconstruction. My gaze was drawn to a strange woman standing beside Diem Phung Thi, and I couldn’t help but wonder who she might be. He said: “My mother. Madam Diem insisted on inviting her to come and take a photo together.” Uncle Thuyen was deeply moved by Diem Phung Thi’s immense generosity and became devoted to her, from this world to the next. In both Diem Phung Thi and uncle Thuyen, I discerned a noble spirit, guided by kindness and always striving towards goodness.

“HELLO THUYEN, HELLO THUYEN, HELLO THUYEN…”

I asked uncle Thuyen if he remembered the final days of Diem Phung Thi. He fell silent. In 2001, a stroke confined her to the hospital for a month. Upon her release, her mind was adrift, and she was reliant on a wheelchair. Yet, she persisted in her work, often long past midday. Even with limited mobility, she directed the artisans in creating her new works.

“Her mind was clouded at that time. Do you think she recognized you?” Uncle Thuyen replied that she seemed to remember him, but her memory was slipping away. She would often repeat “hello Thuyen” again and again. Sadly, such casual greetings became a foreshadowing of her departure, now a poignant memory for those who remained.

“Diem Phung Thi was the guardian angel of my life, not a heavenly being but a mortal. She gave me the strength to carry on and showed me that life was still worth living.”

On August days with a sudden midday breeze, uncle Thuyen led me up the hill to visit the grave of Diem Phung Thi. As we stood there, the sorrow of those twenty past years weighed on his heart. With each visit, he relived the memory of a taxi arriving at his door and him hurrying out to help a woman in a wheelchair. Together, they would slowly ascend the hill to visit the graves of her husband and her mother.

Words: Thuy Tien

Translation: Huong Tra