Classical Chinese dance is a cultural trend that has been increasingly developing in Vietnam in recent years. Not only is it beneficial for health, but this art form also has a rich history and contains aesthetic insights from an Eastern perspective. By exploring the history of classical Chinese dance and its artistry, we become more appreciative of East Asian aesthetic ideals, or more specifically, the discussions on beauty by scholar Pham Quynh. Although he was deeply influenced by Western aesthetics, in his essay “What is Beauty?” (1917), he shared his intimate East Asian sensibilities, thereby providing a suitable theoretical framework for appreciating Chinese dance in Vietnam.

An overview of classical Chinese dance

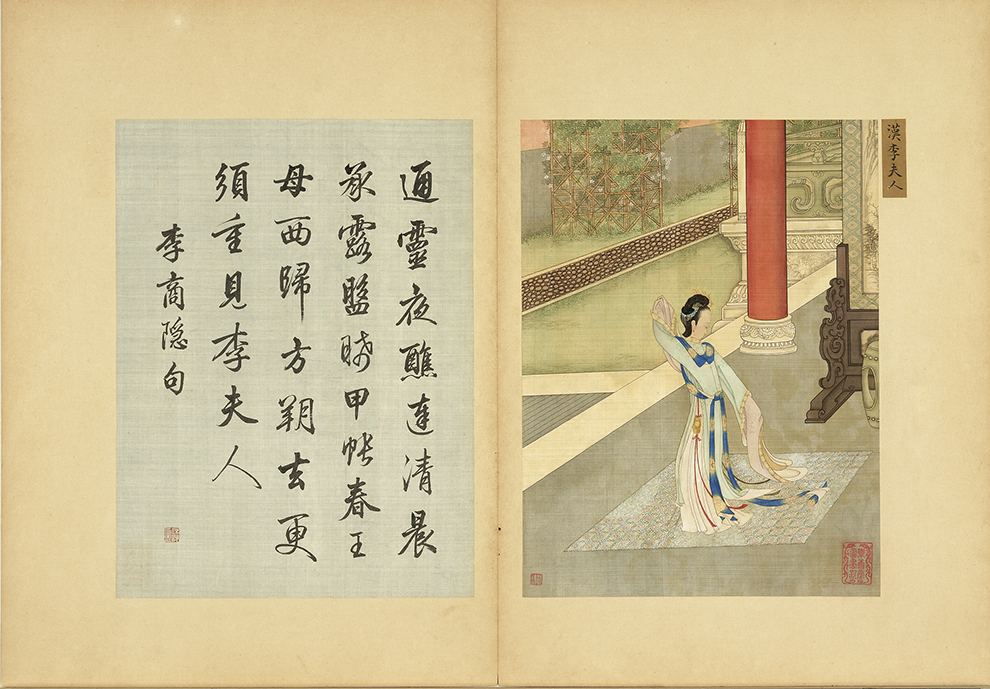

Although the term “classical Chinese dance” only emerged in the mid-20th century, this art form has had a very long tradition, one closely linked to 5,000 years of Chinese civilisation. With each Chinese dynasty, different forms of dance emerged from cultural and social needs, such as the “Shaman dance” of the Shang Dynasty, the “Civil dance” and “Military dance” of the Western Zhou Dynasty, and the “Grand song and dance” of the Tang Dynasty, with ever-increasing aesthetic quality.

Today, when discussing classical Chinese dance, it is impossible not to mention traditional martial arts: “wen wu tongyuan 文武同源 (martial arts and dance share the same origin).” The ideograms for “martial arts” (武) and “dance” (舞) are homophones but have different meanings; although different in essence, they share similar moves. Another important source of influence is the dances of more than 300 types of traditional operas that flourished during the Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties, such as Kunqu and Peking Opera. After its establishment in 1954, the Beijing Dance Academy developed a standardised curriculum for classical Chinese dance by combining Chinese opera, martial arts, and ballet – the last considered a highly scientific and effective training system suitable for physical training at the time. To date, Classical Chinese dance continues to be refined and perfected, using “shen yun 身韵” (body rhyme) and Tai Chi to highlight the Chinese spirit observed today.

Classical Chinese dance focuses on “shen yun” (body rhyme or bearing), “shen fa” (body technique or form), and “ji qiao” (technical skills). Body rhyme is the heart and soul of classical Chinese dance, communicating inner meaning and spirit, focusing on the flow of energy and the transformations of emotion. Influenced by traditional Chinese opera, the essence of body rhyme lies in the Tai Chi concept “yi yi yin qi 以意引氣”: using the spirit to guide the body, and using the body to convey the spirit. Body technique refers to external expressions and methods of body movement, such as footwork and coordinated hand and foot movements, requiring good physical strength and dexterity. Technical skills refer to difficult techniques, including acrobatics, jumps, spins, and flips, usually performed at the climax of a performance. All these elements help to construct the unique language of classical Chinese dance.

The main characteristics of Chinese dance are its rich expressive capacity and immense creative potential, from portraying the personalities and emotions of individual characters to vividly recreating historical, religious, legendary, mythological, and literary stories. This performing art form is closely related to the cultural context of China, while also signifying the universal psychological and spiritual states of humanity. Inheriting a long-standing cultural heritage, classical Chinese dance is diverse, complex, capable of moving people’s hearts, and has a far-reaching influence outside of China, including in Vietnam.

East Asian aesthetics in classical Chinese dance

Chinese dance focuses on inner meaning and conciseness, reflecting the tendency to express ideas, typical of the cultural traditions of China in particular and East Asia in general. In the 20th century, some schools of dance in China incorporated the language of classical European ballet6 while still retaining Chinese national characteristics. This was thanks to “shen yun”, the unique expression closely linked to the dancer’s soul at the core of classical Chinese dance. While ballet focuses on training leg and foot muscles and the precision of actions, Chinese dance requires the coordination of shen yun, shen fa, technical skills, and expressive acts. Shen yun utilises “form, spirit, energy, and rhythm” – using physical posture, emotional expression, inner energy flow, and rhythmic principles to articulate characters’ psyche in the dance drama as well as of the Chinese people.

Furthermore, while the aesthetics of classical European dance were influenced by the tastes of royalty and nobility, classical Chinese dance transcends both the elegance of court dance and the colourfulness of folk dance. The aesthetic value of Chinese dance is inseparable from traditional moral and cultural beliefs, notably the Three Teachings: Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism. For example, the “circle” motif frequently appears in Chinese dance to generate a flowing and seamless effect. It symbolises the concepts of “zhong yong 中庸 (doctrine of the mean)” in Confucianism, “tian ren heyi 天人合一 (unity of heaven and humanity)” in Taoism, and “yuan rong 圓融 (perfect harmony)” in Buddhism. The step pattern “yuan chang 圓場 “(circular walk)”, influenced by Peking Opera, reflects a particular fondness for the aesthetic of the circle. Classical Chinese dance performances are often symbolic, emphasising virtues such as benevolence, righteousness, propriety, wisdom, and trustworthiness; the harmony between yin and yang, heaven and earth; and the reverence for deities. The rules of “desiring to move rightward, first move leftward; desiring to move upward, first move downward; desiring to move backward, first move forward; desiring to move forward, first move backward” represent the coordination of internal and external forces, suggesting that outward expression must originate from within to harmonise opposites.

Due to its philosophical connotation, classical Chinese dance offers an aesthetic experience that elevates the human spirit. An important criterion for evaluating beauty in dance is the positive emotional response from the audience, as music and dance have the effect of “cultivating the mind and nurturing character”. This concept coincides with the viewpoint of Vietnamese scholar Pham Quynh: “In beauty, there is already a lofty benefit, which is to satisfy one’s hearts and minds, allowing them to enjoy a refined and exalted pleasure.” The intrinsic beauty of Chinese dance performances elicits the aspiration for harmony of body, mind, and spirit, and aims towards the ideal of Truth, Goodness, and Beauty.

In “What is Beauty?”, Pham Quynh also offers a poetic analysis of “grace”: “Grace is perhaps that invisible, mysterious element, the ‘finishing touch’ to beauty, without which beauty becomes ‘awkward’ or ‘stiff’. Grace lies in the graceful and supple posture, in the harmonious movement and activity.” Body rhyme is precisely the graceful element that adorns the beauty of dance. For example, techniques such as “the body leading the hands” and “the hips leading the legs” create a natural, fluid motion like flowing water. Without a smooth coordination between “shen yun” and “shen fa” to harmonise body and mind, there will be a lack of grace and vitality, undermining aesthetic feelings. The beauty of “qi 氣” (vital energy) in body rhyme is invisible yet full of solemnity and elegance, and at the same time helps to achieve the principle of “qiyun shengdong”9 (spirit resonance, life-motion) in traditional Chinese aesthetics. A lack of “qi” is a lack of “grace”.

According to scholar Pham Quynh, there are three main types of beauty: the true beauty (the orderly beauty), the charming beauty (the conventional beauty), and the majestic beauty (the sublime beauty). He argued that the Eastern beauty tends towards the charming beauty and lacks the majestic beauty. This view is not entirely accurate when considering classical Chinese dance. Besides celebrating the dignified beauty of traditional femininity, Chinese dance also portrays many other character tropes from gods, kings, generals, and poets in history, to strong female heroines and even modern characters. This versatility, combined with spectacular techniques, tempered by the balance, harmony, and precision of body rhyme, can certainly create the true beauty similar to that found in classical European dance. “Water sleeve dance” (long sleeve dance) is a classic example of the true beauty. The movements of extending and retracting the long silk sleeves, while appearing effortless and undulating like water, require great inner force, combining strength and gentleness, truly representing a beauty that is orderly and refined, yet still possessing the delightful beauty characteristic of East Asia.

Classical Chinese dance embodies timeless and universal beauty through the harmonious interplay between skilful movements and the serene minds of the dancers. The aesthetics of classical Chinese dance, encompassing cultural similarities among Sinosphere countries, explains why this dance form attracts so many practitioners. It is full of vitality and liveliness, rich in humanistic and expressive qualities, yet not as rigorous as ballet. The growth of Chinese dance in Vietnam not only allows participants to practice regulating their emotions, but also serves as a stepping stone for spectators to approach the profound concepts in Eastern aesthetics.

Words & Translation: Tran Dan Vy