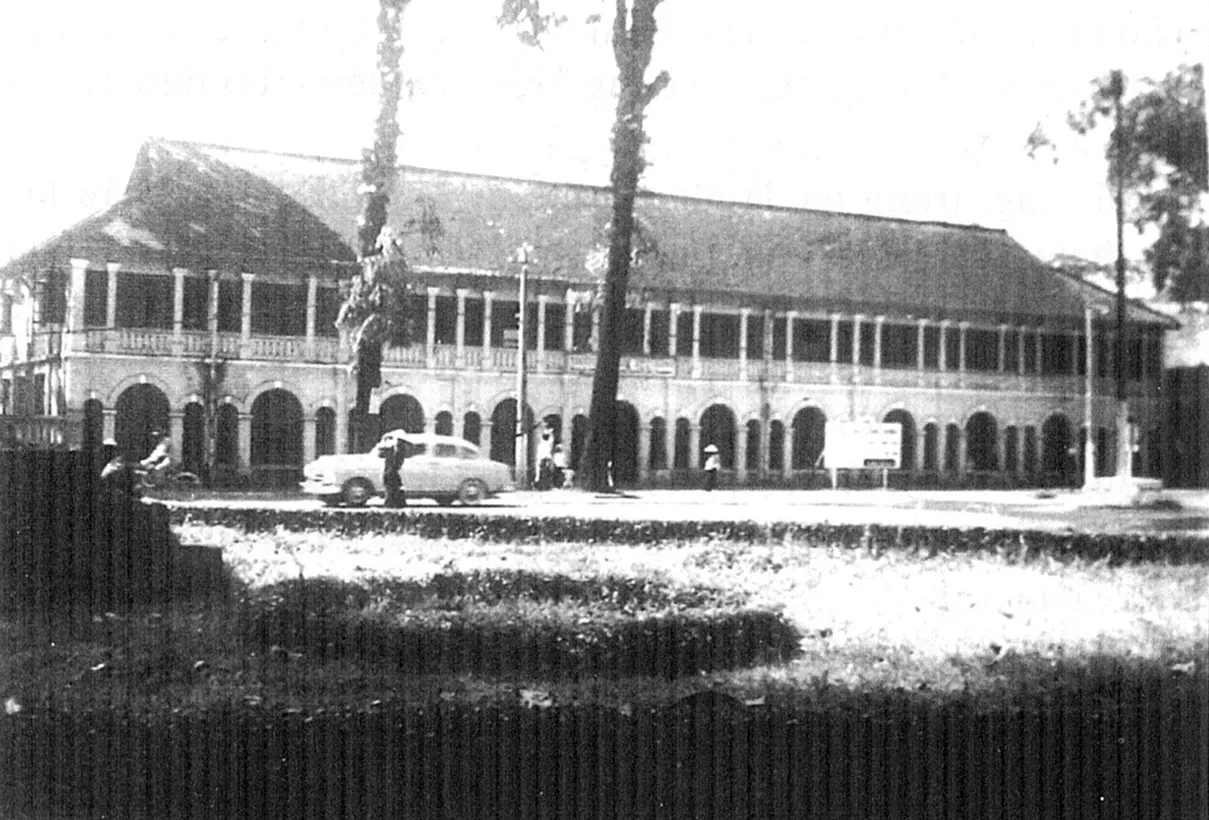

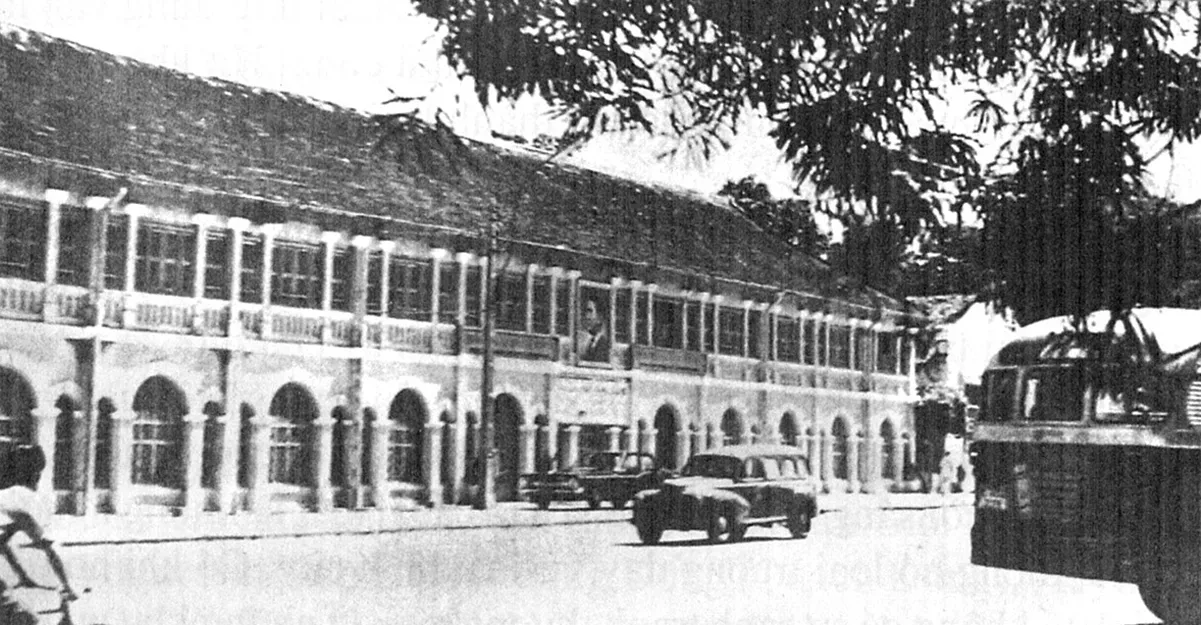

The fine arts of Saigon-Gia Dinh between 1954–1975 was a distinctive trajectory, combining cultural traditions and spirits with choice elements from Western artistic canons, constructing a unique aesthetic language in the wide landscape of Vietnamese modern art. Central to the emergence and consolidation of this regional art scene was the establishment of the Gia Dinh School of Decorative Arts – which would later evolve into Ho Chi Minh City University of Fine Arts. It was founded with the dual mission of training artists in both fine and applied arts. Following the 1954 Geneva Accords, the National College of Fine Arts of Saigon was opened adjacent to the Gia Dinh School of Decorative Arts to address the absence of EBAI in Hanoi, which had been damaged during the Allied bombings in 1943 and ceased operations in 1945.

Can you offer an overview of the art education system in Saigon-Gia Dinh after 1954?

From a theoretical and pedagogical standpoint, the art education system in Saigon-Gia Dinh, and more broadly in South Vietnam, had reached a state of institutional maturity between 1954-1971. The system comprised two principal domains: applied arts and fine arts. There were three institutions for applied arts: the Thu Dau Mot School of Decorative Arts, which specialised in woodwork and lacquer painting; the Bien Hoa School of Decorative Arts, focusing on ceramics and bronze casting; and the Gia Dinh School of Decorative Arts, for visual decoration, printing techniques, and architectural drawing. Concurrently, fine arts was represented by the National College of Fine Arts of Saigon and the College of Fine Arts of Hue.

Southern art professors during this period were typically grounded in applied arts, as they had received foundational training from local applied art schools, while also possessing a deep understanding of classical Western fine arts, which was made possible by their formal education at the EBAI in the North.

Between 1954 and 1975, Saigon-Gia Dinh experienced a dynamic socio-economic environment characterised by a market-oriented economy, a liberal social atmosphere, and a culturally open, pluralistic artistic landscape. What was the impact of such a socio-cultural environment on artistic creativity?

During this period, the Saigon-Gia Dinh art world exhibited a remarkable openness to a wide spectrum of artistic schools and ideologies. From Neoclassicism to Modernism, a diversity of stylistic and conceptual approaches coexisted, leading to considerable intellectual and aesthetic pluralism. This receptivity allowed artists to explore a broad range of expressive languages. They were largely free to articulate personal emotions and subjective experiences, even those deemed melancholic or pessimistic. As a result, many artworks of this era resonate with emotional authenticity and possess an intimate, introspective quality. The prevailing artistic temperament in Saigon-Gia Dinh leaned toward the poetic and expressive, and art was embraced as a mode of emotional and philosophical reflection as natural and vital as breath itself, instead of as a tool for ideological mobilisation.

“During this period, the Saigon-Gia Dinh art world exhibited a remarkable openness to a wide spectrum of artistic schools and ideologies from Neoclassicism to Modernism.”

In addition to the liberal, market-influenced art strongly shaped by capitalist ideals and a broad spectrum of modernist aesthetics, how was revolutionary art in Saigon-Gia Dinh in this era?

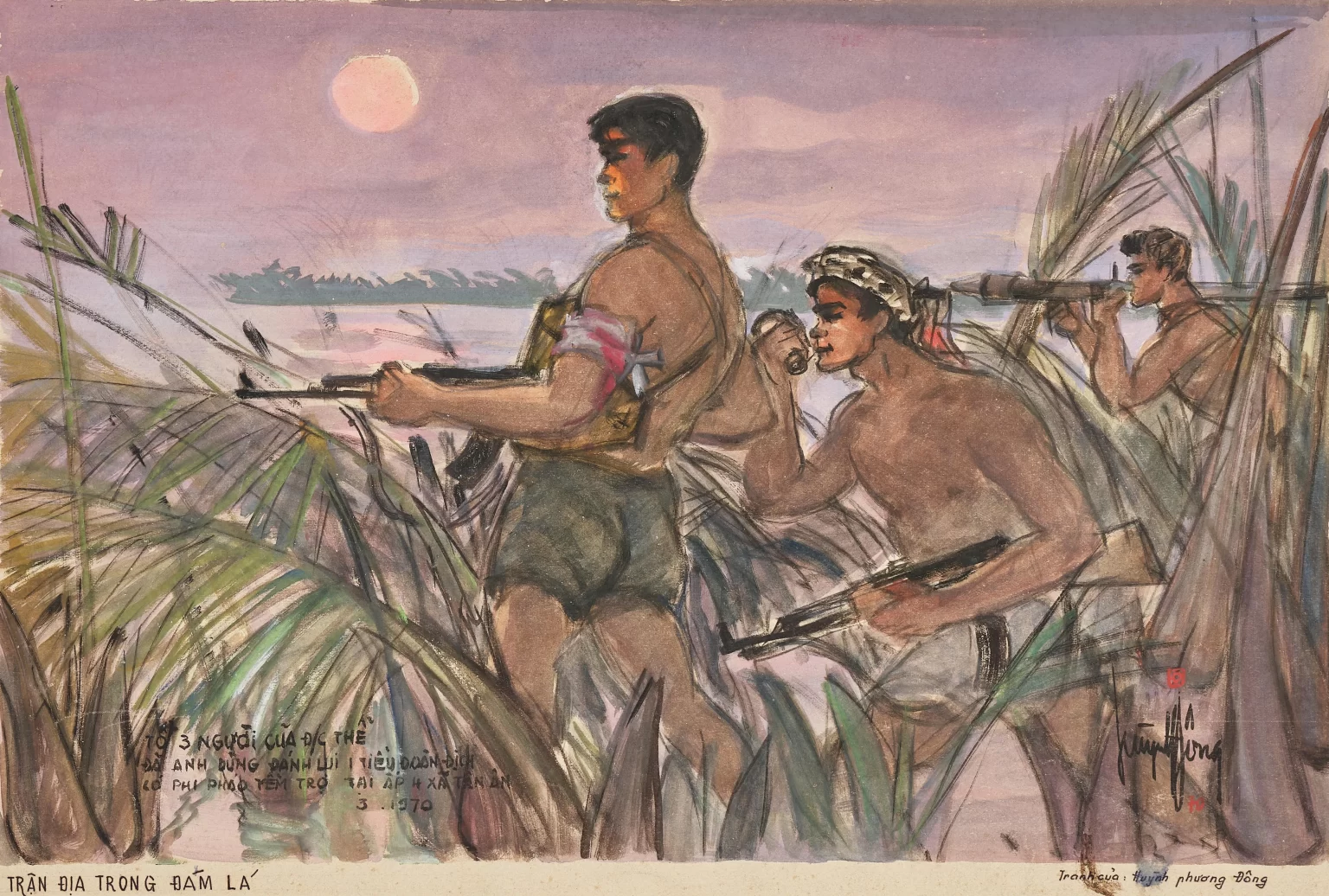

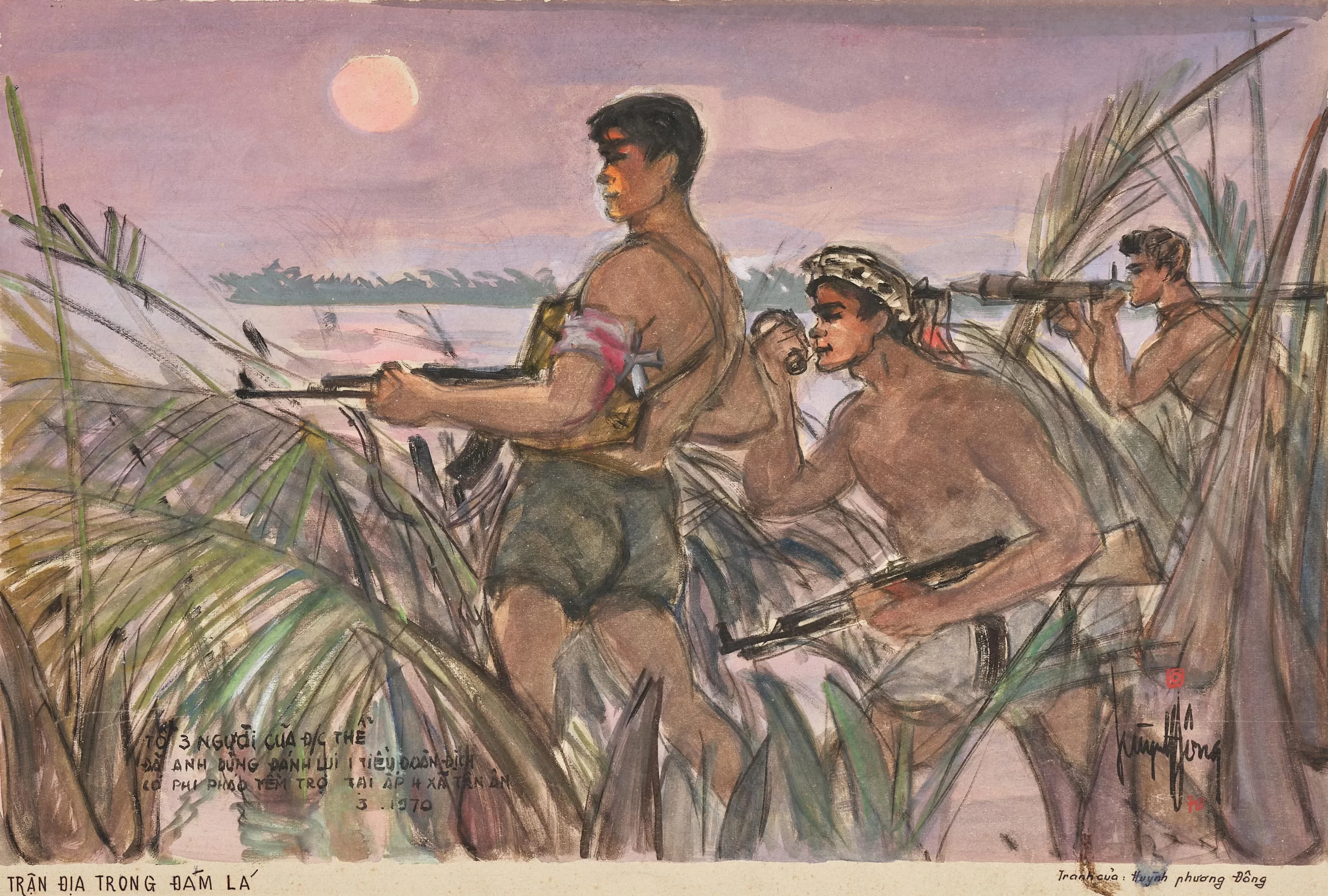

During this period, many forms of visual cultures were openly circulated in the region, such as art for art’s sake, which prioritised pure aestheticism and encompassed a wide range of modernist styles including Realism, Impressionism, Symbolism, Cubism, Surrealism, Fauvism, and so on; sentimental anti-war art, which expressed the emotional toll of war particularly in literature and popular music; commercial art; and propaganda produced under the Psychological Warfare and Political Warfare Divisions of the South Vietnamese military. In contrast, revolutionary art emerged as a body of visual and creative practices developed to serve the national liberation struggle against colonialism, imperialism, and the Southern regime backed by the United States. Under the leadership of the Communist Party, art was mobilised as a tool of ideological resistance, with artists working as cultural combatants and artworks as political weapons for independence, unification, and social transformation.

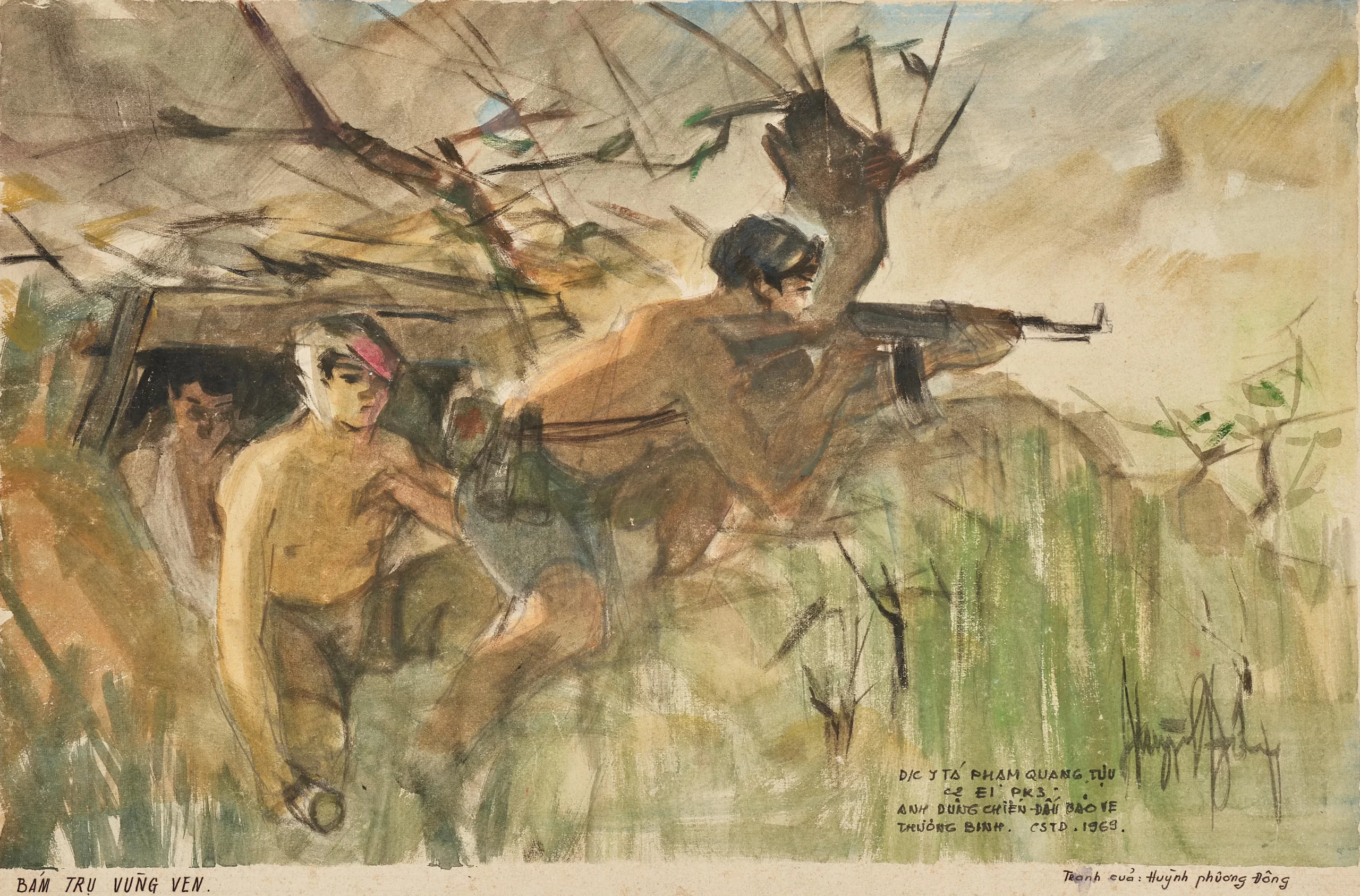

In the liberated zones, art schools and training programs were established to support the resistance movement. The first wartime painting class was launched in Ben Tre under the direction of the Propaganda and Education Department of the Central Southern Region 8. Huynh Phuong Dong, a graduate of the Gia Dinh School of Applied Arts (class of 1941–1945), was a pioneering figure in organising and teaching these underground art classes. In addition, following the establishment of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam in 1960, a number of visual artists would defect from urban centres to join the Resistance in the liberated zones. The Gia Dinh School of Decorative Arts and the National College of Fine Arts of Saigon thus became important incubators for many renowned revolutionary artists, including Co Tan Chau Long, Nguyen Van Kinh, Nguyen Ngoc San, Nguyen Van Thep, Mai Thanh Huong, and Ha Van Duc and others.

What was the influence of the Young Painters’ Association, founded in 1967, on the evolution of art practices in Saigon-Gia Dinh?

The Association was influenced, albeit remotely, by the earlier Creativity Group, a collective of Northern intellectuals and artists who had migrated to the South following the 1954 Geneva Accords and congregated primarily in Saigon-Gia Dinh. The Association’s membership was drawn from four principal sources: graduates of the National College of Fine Arts of Saigon, artists returning from their studies abroad, self-taught and amateur artists, and private patrons. Among these, the amateur artists were particularly bold and assertive. They believed that émigré artists were the true transmitters of the experimental, innovative ethos to the Saigon-Gia Dinh scene. In doing so, they directly rejected the formal, canonical aesthetics of academic art and pejoratively labelled those whose works resembled the styles taught at the EBAI or the National College of Fine Arts of Saigon as “classroom painters”.

From the perspective of artistic creation or the formation of an artistic self, such acts of negation and rupture with classical academic knowledge was a necessity. Beyond the walls of the academy, the Young Painters’ Association embodied a vibrant, youthful energy and asserted a vision of artistic freedom and democratisation, laying the foundation for Vietnamese fine art – one that cannot be denied. However, pedagogically speaking, this spirit of negation must be accompanied by a rigorous process of practice, comparison, and critical reflection. In-depth research, systematic experimentation, and lived experiences remain indispensable to any meaningful reconfiguration of the artistic language.

What were some notable prizes and exhibitions during this period?

The visual arts scene in Saigon-Gia Dinh experienced a remarkable dynamism, fueled in part by the engagement of foreign corporations, particularly subsidiaries of French and American oil companies headquartered in Saigon. Many prominent figures would first gain recognition through competitions such as the “Stanvac Calendar Art Prize” sponsored by Caltex, which reproduced awarded paintings in the company’s annual calendar, and the “Esso Painting Prize” organised by Esso.

In addition, the Republic of Vietnam government also established a number of state-sponsored awards to honour outstanding achievements in visual arts and broader cultural fields. Under the Ngo Dinh Diem administration, the Spring Painting Prize was organised annually by the Cultural Affairs Office (equivalent to today’s Department of Fine Arts, Photography, and Exhibitions). Under President Nguyen Van Thieu’s leadership, this award was replaced by the more comprehensive Republic of Vietnam Presidential Award for Literature and the Arts, administered by the Office of the Special Counsel for Cultural Affairs. This shift marked an institutional broadening of artistic recognition beyond painting to include literary and performing arts. A memorable event occurred in June 1966 when a major international exhibition and awards ceremony was held at the Saigon Municipal Information and Cultural Centre to celebrate the 20th anniversary of UNESCO, underscoring the city’s growing cultural internationalism.

Art exhibitions flourished throughout this era, primarily in Saigon, and were frequently hosted at prominent venues such as Saigon City Hall (now the Ho Chi Minh City People’s Committee building), Saigon Opera House (now the Municipal Opera House), and the Municipal Information and Cultural Centre (near the Opera House). Other important venues included La Dolce Vita Gallery (inside Continental Hotel), Alliance Française Gallery, the gallery of the National Library of Saigon (now the General Sciences Library of Ho Chi Minh City), galleries affiliated with the French Cultural Centre, the National College of Fine Arts of Saigon and the Vietnam-U.S. Association, to name a few.

A landmark event was the First International Art Exhibition in Saigon in 1962, organised in conjunction with the national celebrations for the First Republic of Vietnam’s National Day (26 October 26). This event featured artworks from over 20 countries and marked a significant moment in Saigon’s international cultural engagement. In the same year, the Republic of Vietnam was awarded an Honorable Mention at the annual International Student Art Exhibition in Rome, Italy. The following year, the National College of Fine Arts of Saigon received a Silver Medal from the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for the school’s runner-up finish out of 25 participating countries at the Rome International Student Art Exhibition.

Was the South Vietnamese art market vibrant then?

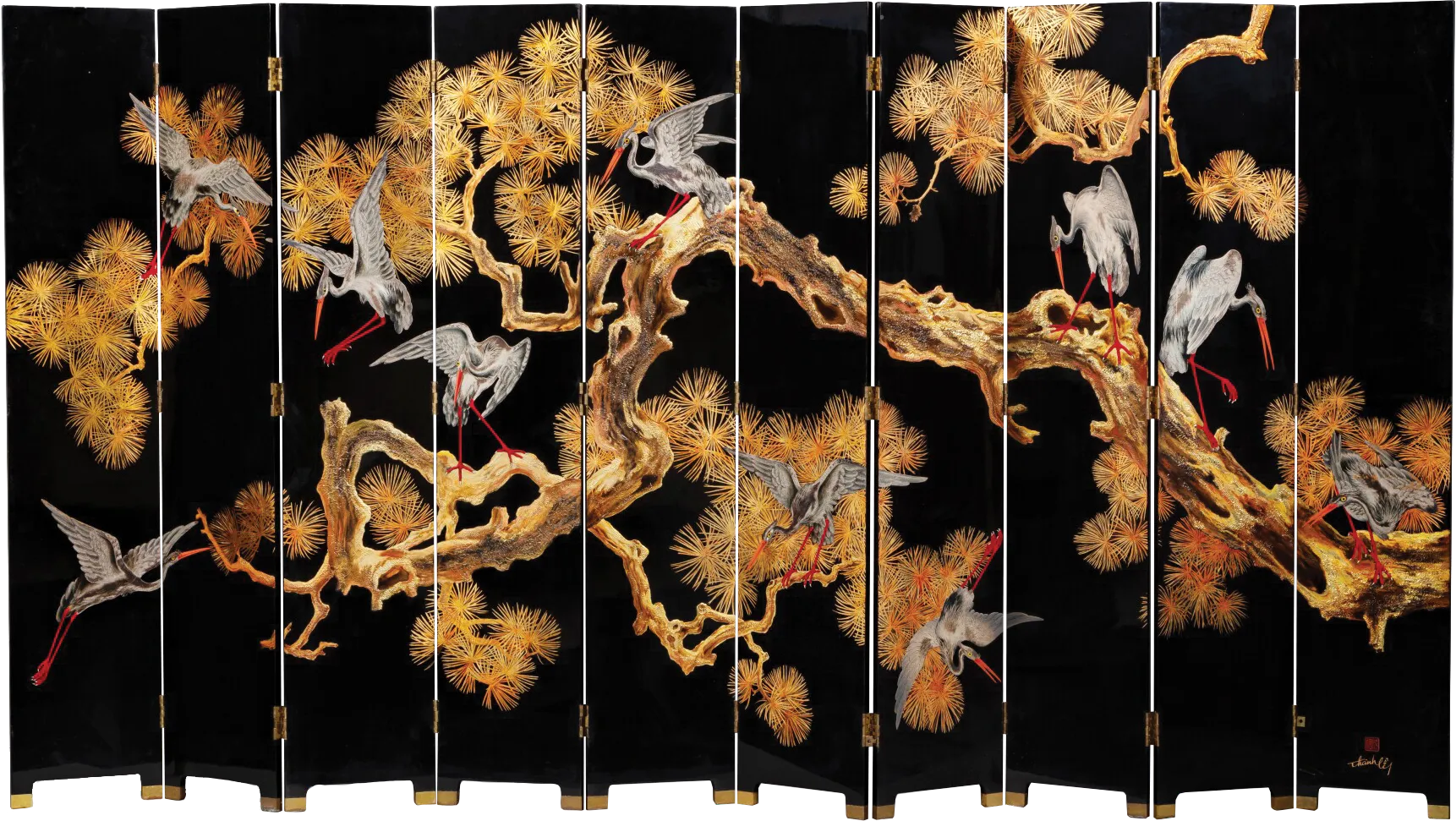

From 1954 to 1975, the art market in South Vietnam, especially in the urban centre of Saigon-Gia Dinh, underwent serious developments shaped by a number of factors. Firstly, the roots of this vibrant market can be traced back to the French colonial era, when crafts and decorative arts had already established themselves within a budding market economy, an early transitional stage into a capitalist framework that witnessed dynamic exchanges between colonial capitalists and the native labour force. Secondly, since the early 20th century, artisanal and decorative art training centres had emerged in the region, gradually expanding in both institutional scale and curriculum. Thirdly, between 1920 and 1954, numerous regional and international decorative art exhibitions and trade fairs were held in the South, showcasing high-quality craft and design products produced by students and artisans from Southern art schools. Fourthly, from 1936 to 1975, Southern Vietnam boasted the largest number of art galleries in the country, forming a vital bridge between artists, artisans, and potential buyers. Although Saigon at the time lacked an organised system of local art collectors, there was a robust clientele among international visitors, particularly Europeans, Americans, and citizens of allied countries engaged in the Vietnam War. A notable example is the American oil magnate John D. Rockefeller, who famously visited artist Tu Duyen to purchase his signature hand-printed woodblock paintings. Fifthly, the annual art competitions and prizes organised by both the South Vietnamese government and the private sector, especially foreign business elites, stimulated not only artistic creativity but also the business of collecting and trading in art. These contests elevated the prestige and marketability of fine and applied artworks, linking art directly to everyday life and the modern taste. Sixthly, urban planning projects initiated by both French and American authorities transformed the Southern urban landscape, giving rise to public and private architectural developments. This urbanisation process created a growing demand for interior and exterior decorations, which in turn drove the consumption of local arts and crafts products.

Moreover, a system of import-export for decorative and craft goods was established. Export channels were steadily supplied by lacquerware companies such as Thanh Le and Me Linh, and by craft villages and kilns located in Tuong Binh Hiep (Binh Duong), Lai Thieu, and Bien Hoa. Generally, artists then were able to sustain themselves economically through their creative output ranging from fine arts to applied arts.

“Artists then were able to sustain themselves economically through their creative output ranging from fine arts to applied arts.”

Thank you for taking the time to share such insightful and valuable information!

Words: Hùng Nguyễn