Your approach to scholarly research is rooted in the core principles of Asian studies as opposed to Eurocentric theoretical frameworks. Why is it important that we unearth and understand the influences of Asian cultures – such as Chinese, Indian, Cham, etc. – on Vietnamese art?

I studied in the Department of Art Theory and History at Hanoi University of Fine Arts. I also studied classical Chinese language, calligraphy and ink wash painting, and spent a considerable time living in the countryside, closely engaging with traditional cultural heritage. At school, my teachers trained me in the History of Vietnamese Art from the outset, a subject I would later go on to teach alongside “Archiving Ancient Texts.”

Even though Vietnamese art education, or the discourse around art in general, always emphasises on reclaiming and revitalising traditional culture, it was, nonetheless, largely influenced by Western cultural and pedagogical paradigms. In addition, the border war with China had reignited the spirit of national independence, prompting a deliberate distancing from Sinitic expressions. As a result, throughout the 20th century, the Vietnamese general public and artists felt a need to sieve off cultural elements imported from elsewhere. At times, this effort took on extreme forms, such as rejections of Modernism, Existentialist Literature, the rigid moral doctrines of Confucianism, and so forth. Such attitudes have softened over time through individual practices that embraced a more benign, eclectic approach. Artists seek to retain what is valuable from both the East and the West, discarding what is not, including those within our own traditional culture.

In “Art of Vietnam – Another Look”, you wrote: “[…] Eastern visual language reflects a different kind of artistic conception [compared to that of Western realist representation]”. How do standards of forms and approaches to art criticism in Eastern ideology differ from the Eurocentric theoretical framework?

As a matter of fact, all artistic traditions originated with an aim to mimic reality, but over time, many grew attached to or served religious functions, leading to a diminished respect for visual realism. Only Greco-Roman art and Western art since the Renaissance, which placed the depiction of human beings at the centre of inquiry, had given rise to a scientific approach to form, grounded in human anatomy and three-dimensional drawing.

These developments, however, did not occur in Eastern art; or if they did, they had taken very different trajectories. Initially, ancient Indian art came under the influence of Greek art via cultural exchanges, especially in the wake of Alexander Macedon’s expedition. It adopted foundational elements of Greek artistic thought – evident in Buddhist sculptures from this era – but eventually strayed away from a strict adherence to proper proportions. In China, there were three main genres of painting: Figure painting; painting of birds, flowers, plants, and insects; and landscape painting – each with their own methods and standards of brushwork. Eastern painting did not emphasise individuality or realistic representations but valued the art of the brush, much like calligraphy, as it was believed to carry man’s spiritual essence.

Eastern art theory is equally rich: In India, there is Ṣaḍaṅga – a set of principles encompassing aesthetics and art; in China, there is Liufa 六法 (Six Principles of Painting), and the broader tradition of Hualun 畫論 (Discourses on Painting), documented over many dynasties by various esteemed scholars and painters, which favoured a measured, aphoristic writing style nearer to philosophy.

Western and Eastern modes of thinking are fundamentally different yet complementary in their humanism, and thus cannot replace one another. That contemporary artists are more familiar with Leonardo da Vinci or Pablo Picasso than Gu Kaizhi and Zhang Daqian is a consequence of Western domination over science, economy, democracy, etc. It is not an indicator of lesser talent in the Eastern sphere.

Literati painting is one of the most emblematic forms of Eastern art, yet it remains absent in the documented history of Vietnamese art, with virtually no intact works surviving to the present day.

As a child, I saw many paintings done in the ink-wash and calligraphic styles, mostly on paper or silk, but they were not well preserved and can no longer be found. These works were authored by Confucian scholars of the old days, perhaps as part of a tradition influenced by Chinese or East Asian art. There was no separate category for literati painting among the old Vietnamese scholar-gentry class; rather, Confucian scholars, Daoist priests, or Buddhist monks would engage in composing and reciting poetry, practice calligraphy, and produce Zen paintings of flora and fauna. They viewed art as the craftsman’s job, whereas writing poetry and reading books were the more honourable pursuits. Even in calligraphy, clarity and formality were privileged in order to achieve “sentences as robust as ropes, letters as square as chests”. When we look at surviving relics from the Ly and Tran dynasties, it is clear that calligraphy and art must have flourished then. Unfortunately, that epoch is so far removed and little has been preserved aside from ceramics and stone carvings.

That we lose out on this tradition is not too damning, however, especially in light of our attempts to completely divorce from the shadows of Sinitic cultural hegemony. Even in terms of ethno-racial identity, the Vietnamese have tended to identify more closely with Southeast Asia.

In your view, what has Vietnamese art gained and lost in the push and pull of Eastern and Western influences?

Unlike in business, gains and losses in art are not so obvious; what seems like a gain might turn out to be a loss, and vice versa. Sometimes, an art teacher of exceptional talent may unintentionally trap students in his own moulding, stifling away any individuality. In contrast, a rundown art school with mediocre teachers may stimulate artists to rise up – a blessing in disguise. Hunger and poverty during the war and the subsidy period had borne witness to many artistic ambitions, leading to the ultimate emergence of painters like Nghiem-Lien-Sang-Phai.

The Eastern current has flown through Vietnam for 2,000 years, while Western influences began to take root in the 17th century with the arrival of Western traders, then increased remarkably under colonialism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. At times, the Vietnamese indigenous culture would be caught between these two currents, yet national independence always takes precedence over cultural concerns. Art is only one facet of culture, but can be its highest expression when meaningfully aiding the broader cause of national sovereignty – otherwise it is but a prop. The act of distilling and transforming East-West currents into valuable lessons for Vietnamese art depends on not all artists but a few masters. For example, songs and poems of the pre-war period drew from an amalgamation of classical Asian verses and French literature. The same can be said about modern music and literature.

Today, the global flow of information is immense, which can in turn easily overwrite or dilute national identity. This happens on a daily basis, even to our surrounding languages. In the arts, generations have grown increasingly apart, leading to a lack of mutual understanding; engaging in quarrels over such fundamental incongruencies is meaningless. It is a shared global reality that small, peripheral countries and ethnic groups face threats to not only their national security and economic developments, but also ethno-cultural preservation – a decisive factor in a nation’s destiny. An economic compromise may be tolerated, but to compromise in culture is to surrender key aspects of national identity.

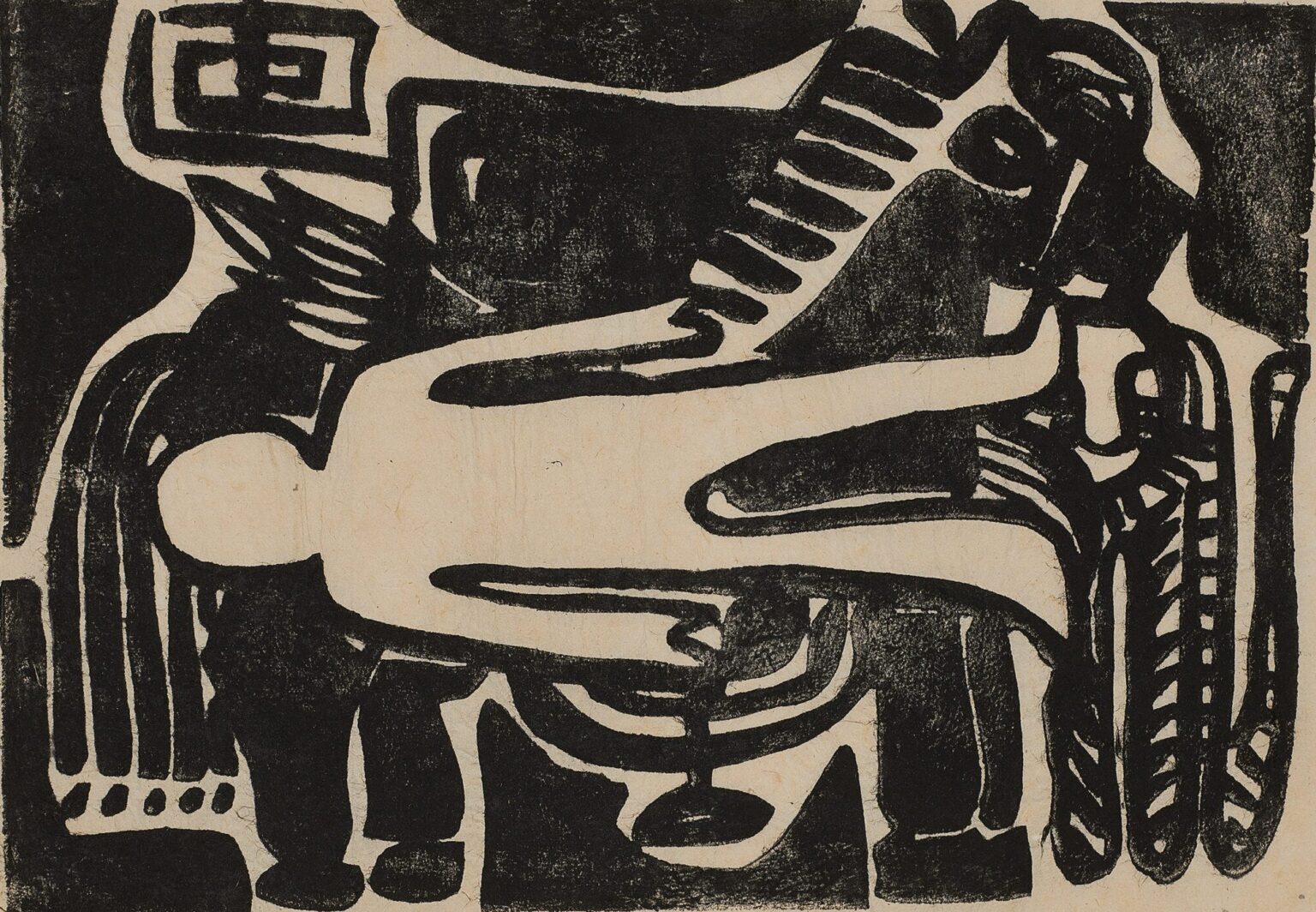

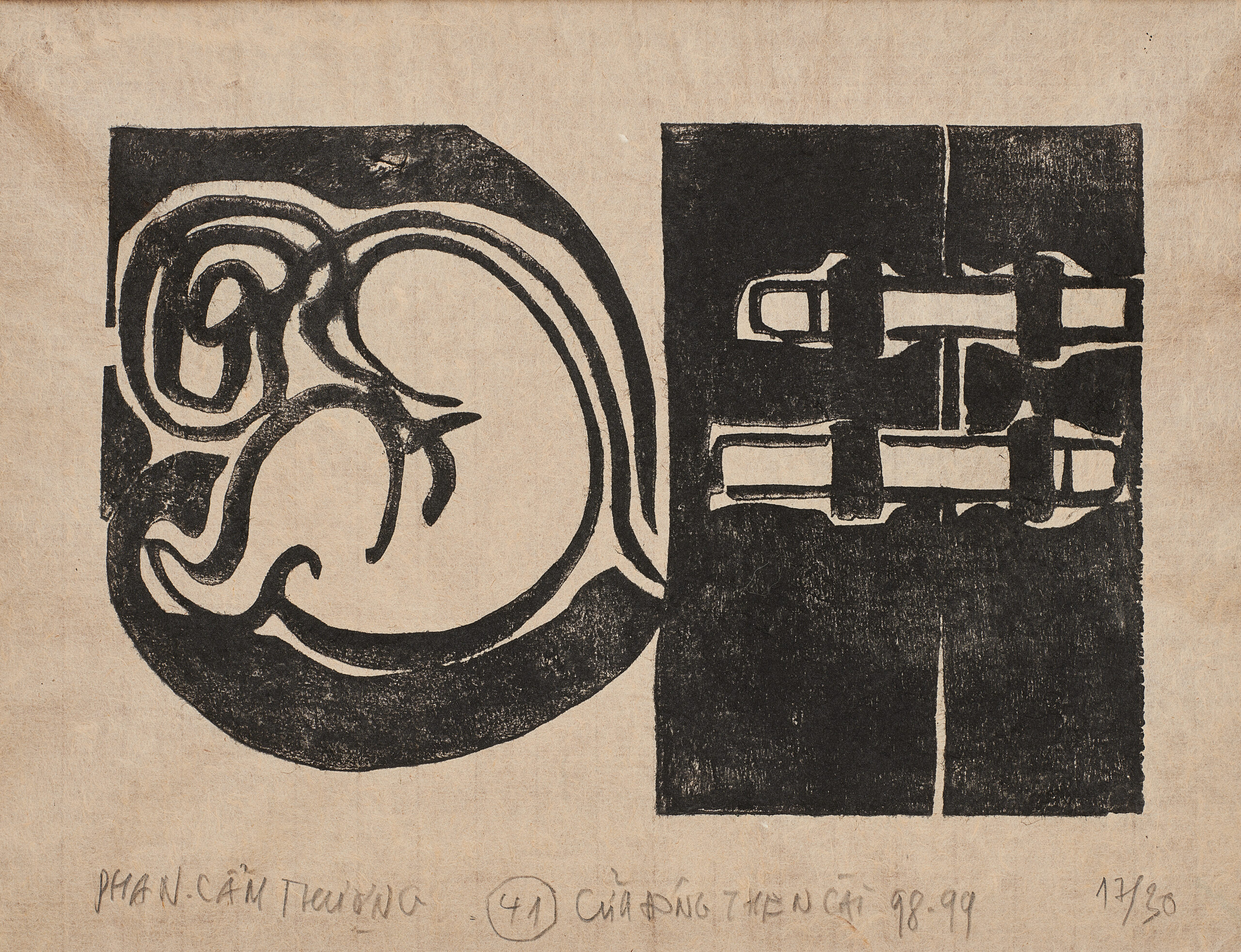

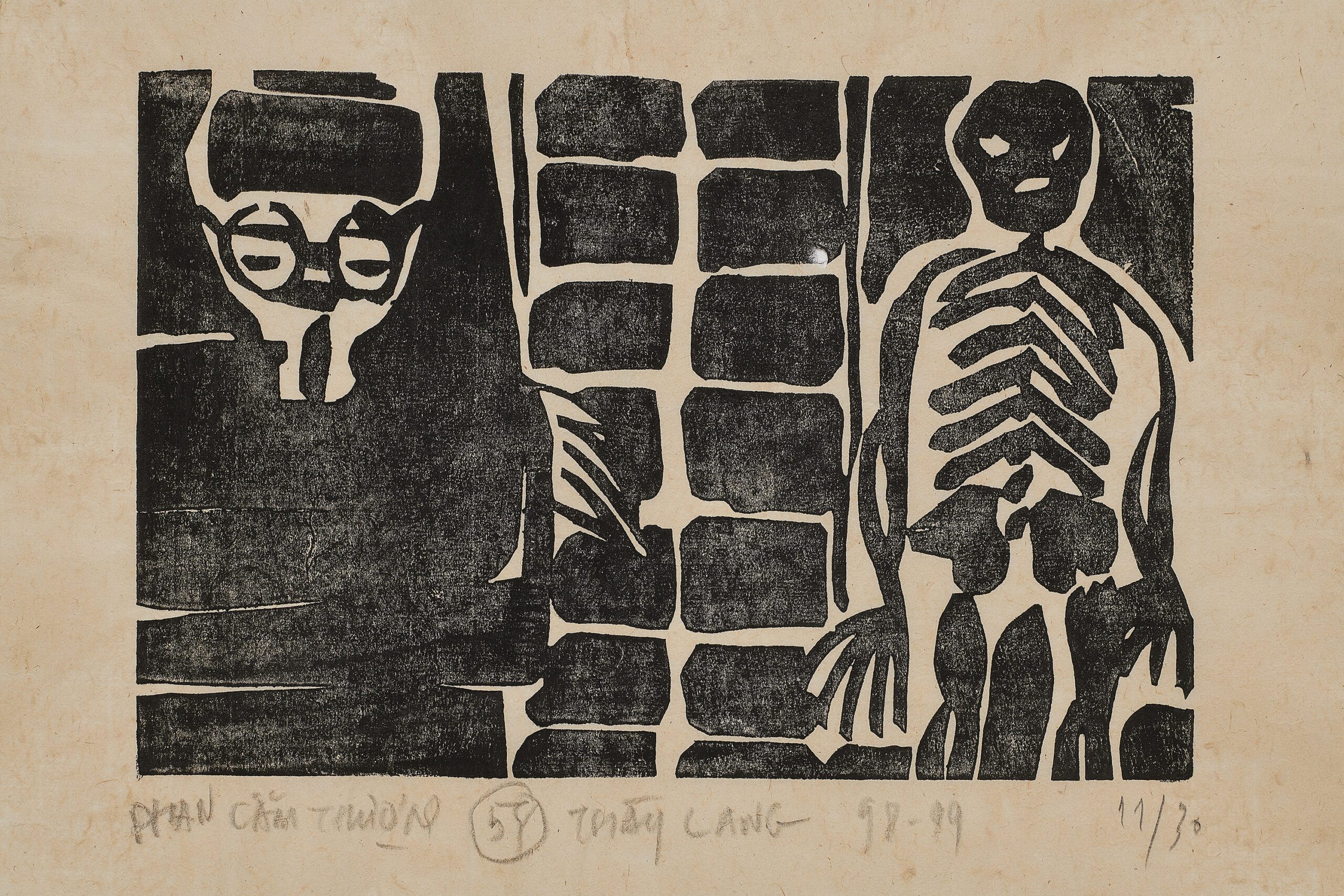

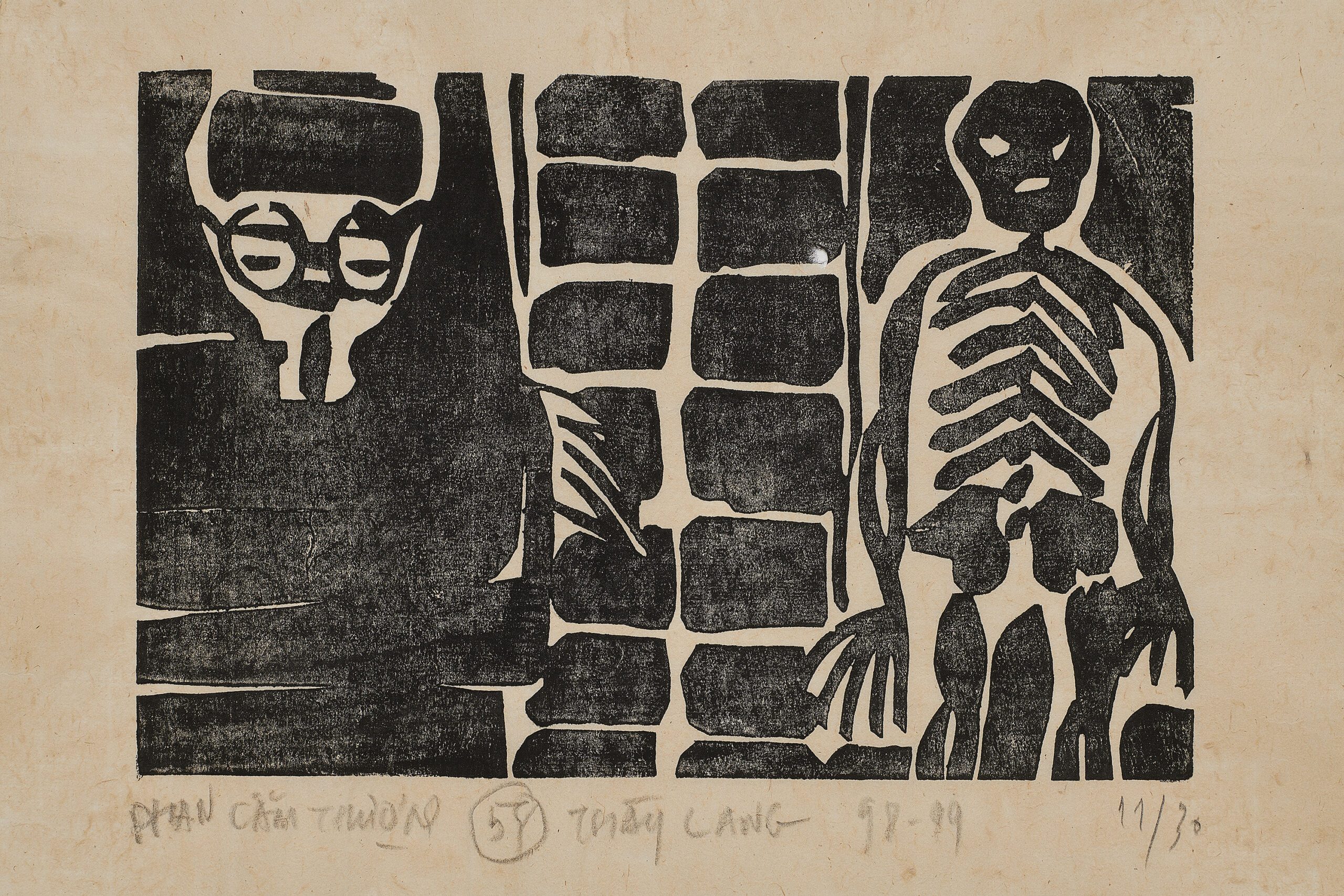

You are a researcher and a critic, and at the same time a painter whose artistic practices are steeped in Vietnamese and Eastern sensibilities. Among your works, the sixty-piece woodcut series “Sixty-year Cycle” (1998–1999), rendered in bamboo charcoal ink on paper, stands as a monumental and representative project. Could you share with us the context in which it was created, and the expressive language it employs?

In 1997, gravely ill to the point I thought death was around the corner, I bought 60 small woodblocks and painted directly onto them 60 narratives, each one a reflection on human life, entitled “Sixty-year cycle”. At the time, I couldn’t manage all the work alone, so I enlisted three university students to help with carving and printing. 60 woodcuts were completed, each made into 30 prints. Over the course of 1998, 1,800 prints were produced, totalling 30 full sets of woodblocks.

New York-based dealer Judith Day, who visited the showcase, purchased one set then lent it to several American colleges for exhibition, which drew interest from some collectors. The series begins with themes of different Eastern philosophies and religions; from block number 16 onward, it turns to idioms of Vietnamese customs and traditions. Strangely enough, after completing the project, I also recovered from the illness.

An unique feature of Eastern aesthetics is the use of empty spaces, which appears frequently in your works.

In “Liuchang 六長 – Six Merits of Painting,” Liu Daochun wrote: “Wu mo qiu ran 無墨求染” – let there be shades without ink, referring to the beauty made possible by empty spaces in painting. All elements of art, from lines to colors and forms, seek to construct a sense of space. Though invisible and perceived only through relations between shapes, space is what we experience in our aesthetic encounter with paintings and sculptures. To look at an abstract painting is to take in all of its space. However, space can also naturally conjure itself over the course of painting and sculpting, particularly when studying the spatial dynamics of the carvings on village communal houses, which unfold horizontally in patterned sequences.

In addition to working with paper, over the past two decades you have expressed an interest in lacquer – a medium ubiquitous in both the handicrafts and fine art traditions of many Asian countries. You remarked: “However, in the end, it should be understood that lacquer is not just material but a way of creating. Material means nothing by itself.”

I have been drawn to lacquer for a long time because it feels authentic. These days, AI can generate any type of art, except lacquer paintings. The material itself inherently exudes beauty – even a bare panel can be evocative. This becomes an inhibition for artists who pursue the aesthetic immanence and craft-like appeal of lacquer; the process is also arduous and expensive. Nevertheless, I have always viewed lacquer as just a material; in medieval times, there were materials and techniques which produced effects not unlike those found in modern lacquer painting, or perhaps closer to traditional gold lacquer painting. What matters most is how one paints.

In an increasingly interconnected world, the power balance appears to be gradually shifting towards the East. What are your predictions regarding the future landscape of art in the coming decades – globally and in Vietnam?

I don’t think there is any such thing as a power shift towards the East. Rather, what we are seeing now is Eastern art being rediscovered, while non-Western countries are gaining economic and cultural footholds following periods of colonialism and underdevelopment, and this includes the contemporary art scenes across East Asia.

The development of Western art has remained closely aligned with Western philosophy; within this tradition, it is precisely the humanistic and scientific approach towards artistic creation that makes Western modern art so appealing. In the East, culture and the arts have been facing tension between traditions and the Western techniques taught in school. As the design industry grows, there is indeed a strong incentive to equip oneself with Western methods of visual construction in order to meet practical demands of production.

As an educator, what do you think of the quality of the current generation of art researchers and practitioners? What advice would you give those who wish to pursue a career in the arts?

Today’s youths are very smart and perceptive in all aspects, yet they lack the cultural depth pivotal to long-term creativity. Cultural knowledge cannot be acquired solely through teaching and learning in class, but demands deep attunements over time, or an intuitive grasp. Young artists who are just starting out often immediately dive into a contemporary style, rendering it in a task-oriented manner, with a surface-level understanding of their own profession all accessible on a mobile phone. That is why even though there are many capable artists, can anyone claim to have surpassed Bui Xuan Phai, whose impact was not only artistic but deeply cultural?

I don’t venture to offer anyone advice in doing art, as I would have given myself one if I could. I cannot speak to other artistic industries, but in painting there is no such thing as a prodigy. It is said that Picasso once remarked at a children’s art exhibition: “It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a kid.” Similarly, Paustovsky said something along the line of: “A child’s imagination is vast and rich, but will fade in time. Only those who retain that childlike wonder into adulthood become writers.”

Our sincere thanks for your generous sharing, reflections and observations!

Words: Ace Le