Congratulations on your achievements over the past year! Your works frequently feature imagery and symbols inspired by Dong Ho folk woodcut paintings, biblical allegories, and Catholic historical figures. Could you share what drew you to these specific themes?

These images came to me very naturally. Firstly, as a Vietnamese person, I am deeply captivated by our indigenous cultural iconography. Secondly, I was raised in a Catholic family; religious art and dogmas have been etched into my mind since childhood. As I matured, the synthesis of my formal fine arts education and the philosophical and theological insights gained during my time in the seminary allowed me to resonate deeply with St. Augustine’s thought – that God is present in all forms. Furthermore, the intersection of culture and religion has always been a latent current in Vietnamese painting. Therefore, I choose to express what is most instinctive and innate to my being.

How do you deconstruct and restructure these icons? Do you preserve the original morphology of the symbols/characters, or are they transposed into entirely different contexts?

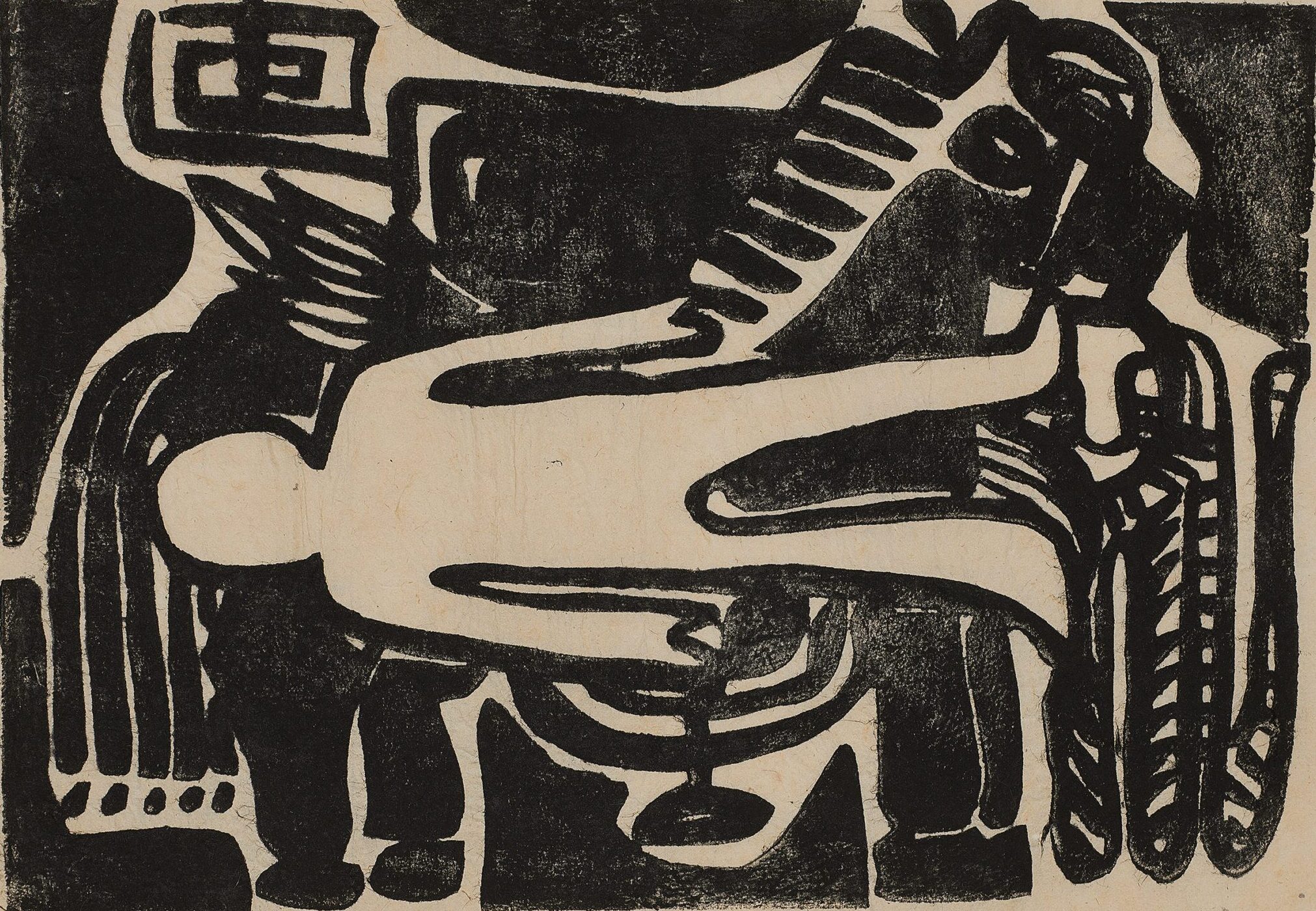

Let’s look at a specific example: the painting “Bình An” (Peace, 2023), which features details from the satirical folk painting “Chuột Múa Rồng” (Mice Dancing with Dragons).

“The characters in this painting can be distinguished as two mice holding long poles to raise and lower the dragon figure, one holding a pole attached to the dragon’s head, and another at the tail. The fundamental satirical element is shown in the long mouse tails, an allusion to the long braided pigtails (queues) worn by the Chinese during that period.”

– (Excerpt from “Vietnamese Folk Paintings – Collection and Research” by Maurice Durand)

In my practice, I adopt an approach that balances the preservation of core morphology with a total shift in the narrative context through a contemporary lens. Morphologically, I maintain the essential appearance of the characters – such as the mice – to honour traditional iconography and maintain a recognisable identity. Contextually, however, I transform the setting entirely. Instead of the original satirical scenarios, I place them in a new environment: a dialogue between the Yang (the vitality of the mice) and the Yin (spirituality, paper horses, marigolds). Structurally, the novelty lies in the presence of metaphorical elements like “thorny vines.” This evolves the painting from a historical anecdote into a fragment of internal conflict and the silent evolution of culture within every modern individual.

Mosquito netting possesses a translucency similar to silk. How did you manipulate this material in your works for the exhibitions “The sky is my blanket, the ground is my mat, under heaven’s canopy, I lay where I am at”, “DUCTIN,” and the “Dogma Prize 2025”?

In each exhibition, I treated the netting differently, depending on the spirit and content of the project.

In “The sky is my blanket, the ground is my mat, under heaven’s canopy, I lay where I am at”, most of the fabric was kept flat, with minimal layering or volumetric sculpting. This treatment stemmed from the fact that the series explored Vietnamese culture and folk art, which are inherently symbolic, reductive, and oriented toward a 2D visual logic. Here, the translucency was not intended to create spatial depth but rather functioned as a layer of memory or a cultural veil draped over the present.

In “DUCTIN” and the “Dogma Prize 2025,” the content focused more on the internal psychological layers of the human condition. I exploited the translucent properties of the netting more explicitly by separating and overlapping multiple layers of fabric, arranging them in space to evoke a sense of depth. The viewer does not merely look at the surface of the image but can “pass through” the material layers, as if stepping into different strata of the psyche and the self.

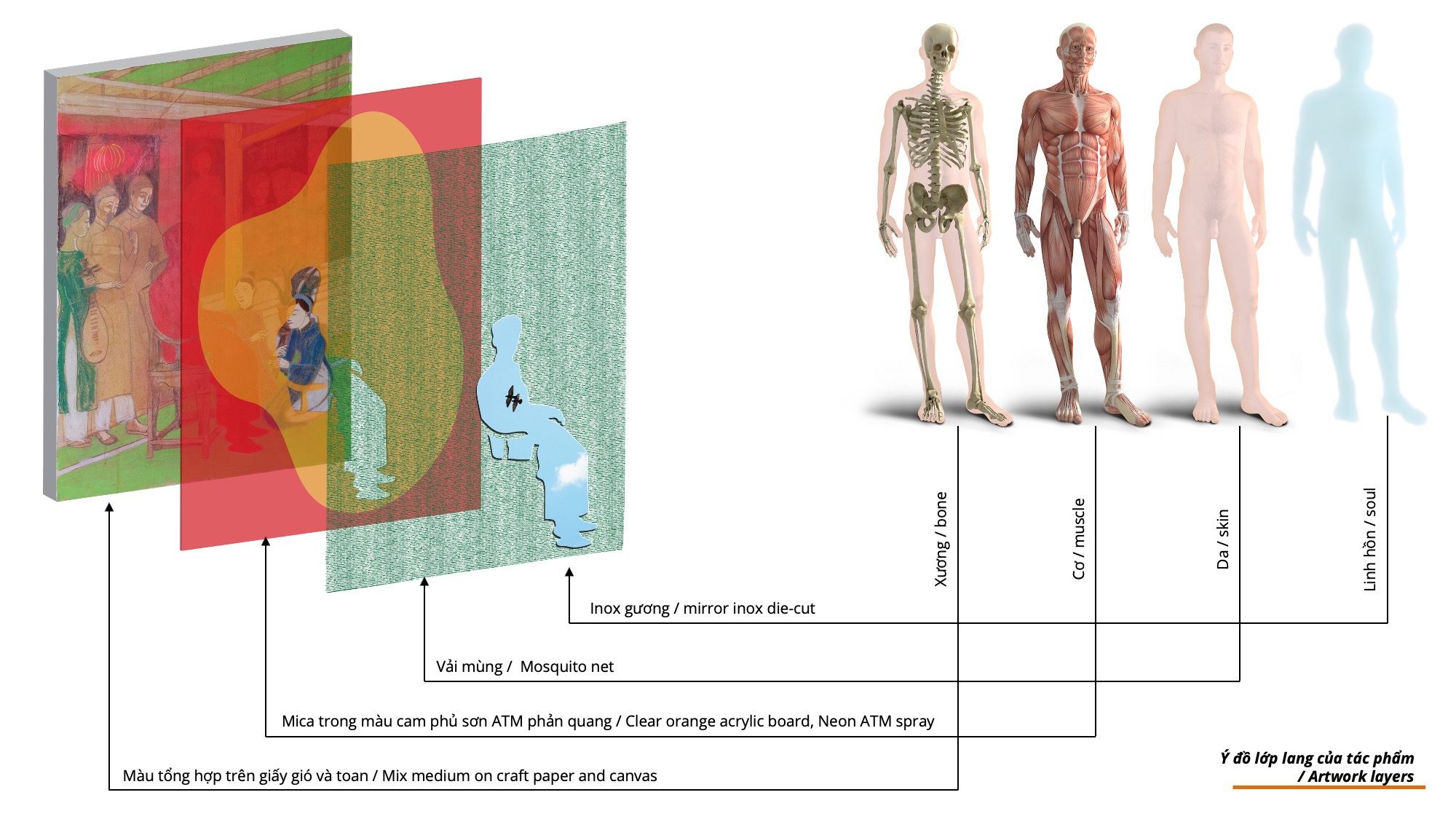

In your series “Heart”, the final works consist of four material layers corresponding to four “anatomical” layers of the human body: Do paper / Canvas (Bone), Orange mica (Muscle), mosquito netting (Skin), and mirror mica (Soul). Could you elaborate on the anatomical and conceptual logic behind this series?

Observing my own experiences and those of people around me, I noticed that everything we strive for converges on the search for peace. To understand what peace is or how to find it is a long journey through the many spectrums of life. These 12 works correspond to 12 archetypal human portraits: from the common labourer to the high-ranking official, from an optimistic temperament to everyday existential angst. The interplay of materials reflects the complexity of humans within social relationships.

Rather than being disparate portraits, the series as a whole forms a spiritual odyssey: moving from external material desires and prosperity to eventually touching true peace within the soul. There, the viewer does not just observe a character but sees their own reflection in the “mirror stainless steel” layer of the work.

– Dó paper & canvas (Bone): The core foundation, defining the frame. In painting, practicing on paper and canvas is fundamental.

– Orange mica (Muscle): Movement, energy, and reaction to the environment. It acts as a filter for the “bones,” representing resilience in a multi-dimensional perspective.

– Mosquito netting (Skin): A fragile yet sensitive enveloping membrane. It is through the skin that humans perceive objects directly, and it serves as the external manifestation of emotion.

– Mirror mica (Soul): The deepest stratum, where the ego and self-awareness are reflected.

The layering in the “Faith” series obscures the portraits of eight Vietnamese Martyrs. Why did you choose these specific figures, and how does their presence relate to your own faith?

The eight portraits of the Vietnamese Martyrs were chosen based on the artist’s personal connection, including: St. Luke Vu Ba Loan (Priest), St. Peter Doan Cong Quy (Priest), St. Andrew Dung-Lac (Priest), St. Dominic Pham Trong Kham (Layman), St. Agnes Le Thi Thanh (Laywoman), St. Paul Tong Viet Buong (Judge), St. Michael Ho Dinh Hy (Official), and Blessed Andrew of Phu Yen (Layman).

The overlapping layers of mosquito netting that obscure these portraits speak to a part of history that is rarely mentioned and almost forgotten. This is a crucial milestone in the nearly three-century-long formation of the Vietnamese Catholic Church, from the 17th to the 19th century. Revealing parts of the faces – especially the eyes – through tears in the fabric alludes to the torture and martyrdom they endured to protect their faith. Though their bodies were broken, their gaze remains a sign of inner steadfastness and spiritual strength. In this work, faith is not presented as an abstract concept but is manifest through human endurance, persistence, and the choice between life and death. They are not just historical figures but symbols of a faith lived through various social strata, professions, and circumstances.

With my family’s Catholic tradition, I received the sacrament of Baptism at birth, receiving the patron saint name Luke Vũ Bá Loan, an elder among the 117 Vietnamese Martyrs. The seven other chosen saints also represent the diversity of the faithful community: priests, laypeople, royal officials, and judges. Placing them together emphasizes that holiness is not limited by social status.

I understand that mosquito netting was an improvisational solution in your creative process. How have you processed and optimised the fragility of this material?

I approach it intuitively: experimenting while creating. That process of trial and error becomes an essential part of my methodology. To optimize the material, I test various treatments, from stretching multiple layers to create spatial depth to reinforcing certain points with frames, stitching, or adhesives to maintain the overall structure. As a result, the netting retains its original essence while being durable enough to exist in an exhibition space.

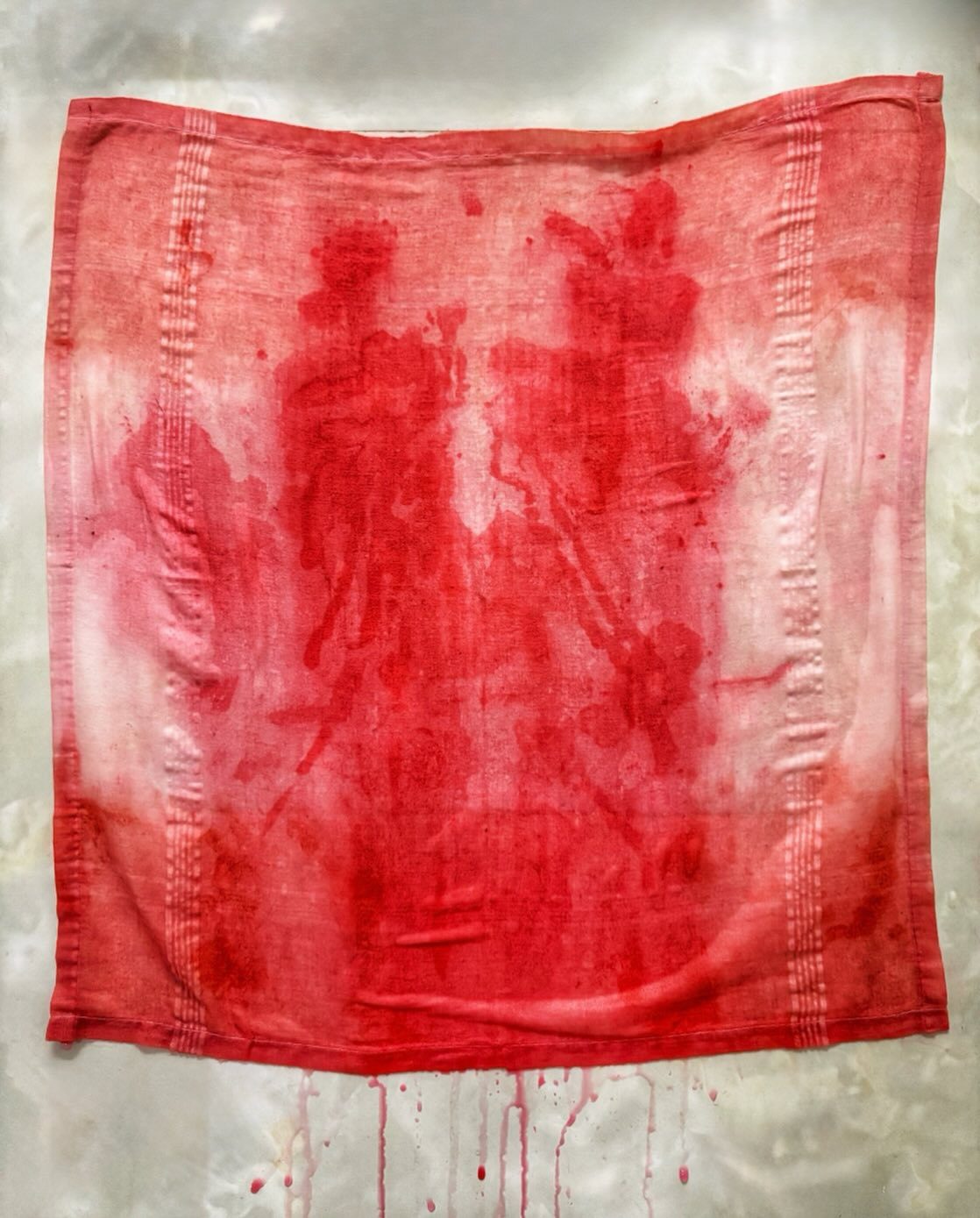

One of your works was inspired by the Shroud of Turin. Drawing from your theological training, how do you apply Biblical parables to realize a work of art?

During my time in the seminary, reading the Bible and theological texts instilled in me a habit of meditation, which I later translated into a visual language. I do not approach Biblical parables as direct illustrations; instead, I view them as “open texts”, where symbols, traces, and silence are just as significant as the narrative itself.

When creating this piece, I did not attempt to replicate the image on the Shroud of Turin specifically. Instead, I focused on the sense of a real body’s presence: the faint imprint of a physique, the red stains suggesting wounds, and the fabric surface carrying the memory of a past event. I transformed these meditations through material handling: allowing the color to soak deep into the fibers, letting the stains bleed freely, and leaving empty spaces as signs of that which cannot be fully seen.

I consider the act of creation akin to a contemplative practice: reading, listening, and allowing the image to gradually take form over time. Consequently, the work does not aim to offer a dogmatic assertion but opens a space for reflection, where viewers can confront memories of suffering, death, and the possibility of transcendence.

A bright, neon, and “joss paper” palette is a signature of your work. How does your use of this colour scheme relate to folk inspirations and local legends?

In Southern Vietnam, vibrant and high-contrast colours often appear in glass altarpieces, hand-painted signs, or ritual offerings. These images are etched into my visual memory – both sacred and mundane.

Furthermore, I also reference Dong Ho paintings from the North, where the traditional palette – vermilion, pagoda tree yellow, leaf green, charcoal black – is derived from natural materials yet achieves a high degree of brilliance and flatness. Placing these two sources together, I realised a commonality: both Southern glass paintings and Northern folk art use symbolic, direct, and highly ritualistic colour systems.

The “joss paper” element also relates to how Vietnamese people envision the afterlife through brilliant, metallic materials. I am interested in the ambiguity between the sacred and the profane in those practices. I use the neon palette as a visual language to speak of folk memory, oral traditions, and the layers of local myths that continue to transform in today’s life.

With your experience in advertising, what skills have you applied to your art practice?

First and foremost is the ability to build structure and narrative for a work: from developing an overarching idea and defining the content axis to how individual pieces link into a series or a complete exhibition. Writing concepts, editing content, and placing works within a broader discourse allow me to think in terms of long-term projects rather than just isolated pieces. Additionally, there is the production management mindset – planning, material testing, progress and budget control, and coordination with technical teams. I also utilise my experience in communication and project presentation.

What art projects are you harbouring for 2026?

I am simultaneously developing plans for my next exhibition projects and have begun the research and material testing phases. At this moment, I don’t wish to announce the specific details of each project, but both will continue the consistent concerns of my practice.

Thank you, artist Nguyen Duc Tin, for such enlightening insights. I wish you a very productive new year with your upcoming art projects!

Words & Translation: Trao