Phoebe Scott is Senior Curator and Curator of Research Publications at the National Gallery Singapore. Previous curatorial projects include “Radiant Material: A Dialogue in Vietnamese Lacquer Painting”, National Gallery Singapore, (2017); “Reframing Modernism: Painting in Europe, Southeast Asia and Beyond” (2016); “Between Declarations and Dreams: Art of Southeast Asia Since the 19th Century”, (2015–ongoing). She holds a PhD in Art History and Theory from the University of Sydney, on the subject of modern art in Vietnam. She is currently also an Adjunct Lecturer in Art History at the National University of Singapore.

Congratulations on the resounding success of the groundbreaking exhibition “City of Others: Asian Artists in Paris, 1920s–1940s”! It is indeed one of the most comprehensive surveys of Parisian art history through Asian lenses. Could you share with our readers the curatorial ideation and rationale behind the different sections of the exhibition?

Thank you so much for your enthusiasm for “City of Others”. The curatorial process took place over many years, as we had originally begun to research the exhibition as far back as 2019! We are so delighted to finally be able to share this exhibition with the public. It has been a huge undertaking as the show features over 220 artworks, including painting, sculpture, lacquerware, decorative arts, and a further 200 archives or archival images, in seven sections spread across three gallery spaces.

Our key rationale for the exhibition was to “re-map” Paris from the point of view of Asian artists who worked or exhibited there between the 1920s and 1940s. When visitors come to experience the exhibition, they won’t see the same styles of artwork that they might find if they open up a textbook on modern art. Instead, they will see zones of the art world that were interesting and meaningful (or profitable!) for the Asian artists who worked in Paris at that time.

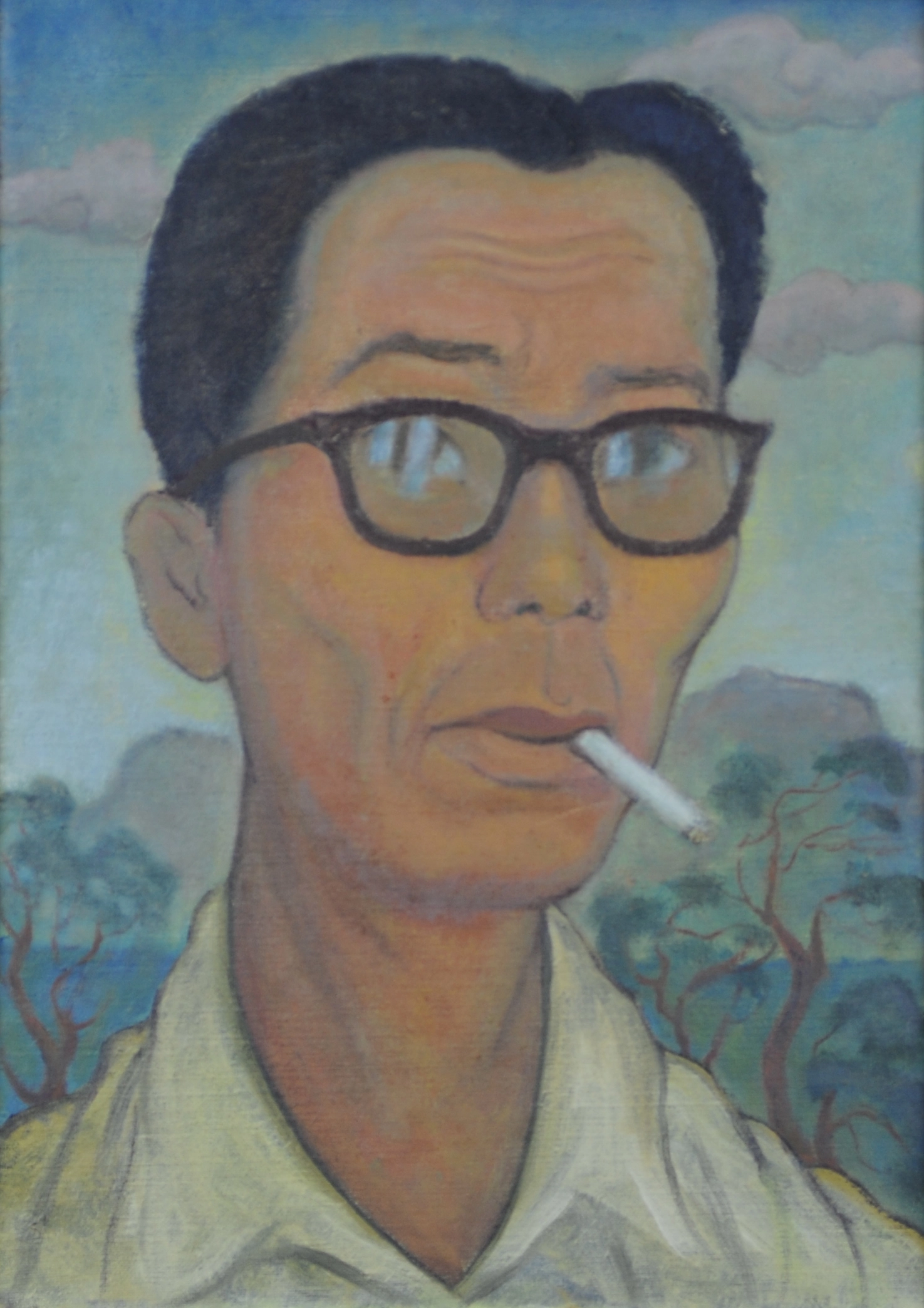

The exhibition opens with a “Preface” section of portraits – mostly self-portraits – by these artists during their Paris period. This allows us to see how they presented themselves to the world, conveying modernity as well as references to their Asian roots. Then we move to the section “Workshop to the World”, which is about Asian artists and artisans participating in the development of decorative arts in Paris. The colours and finishes of the exhibition space evoke the gilding and lacquer that were popular then.

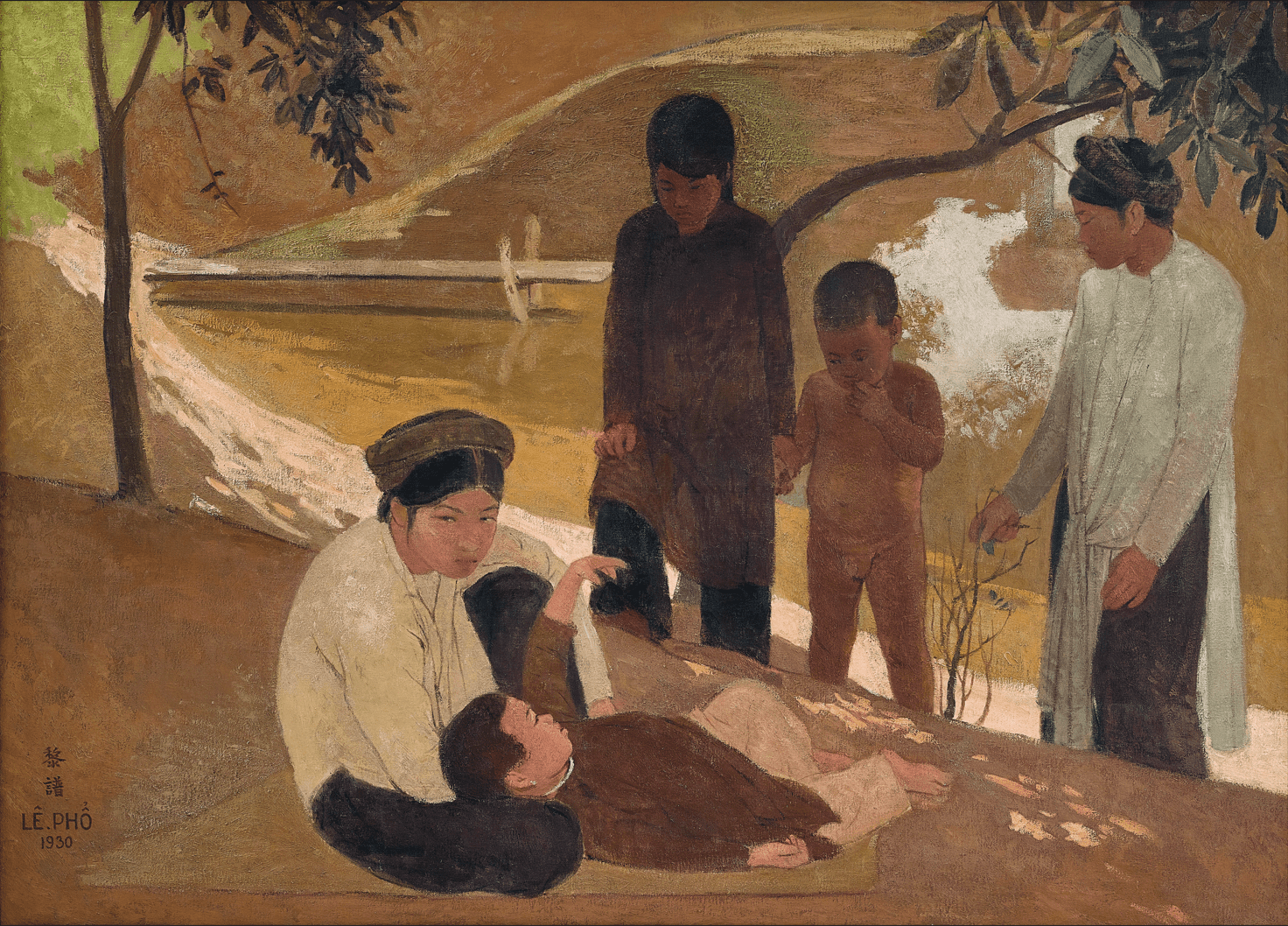

The next section, “Theatre of the Colonies”, is about special Expositions, salons and exhibition sites in Paris dedicated to artists from the colonies, including French Indochina. It is a complicated legacy, as these artworks were often presented within a framework of colonial propaganda, especially at venues like the 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition. And yet for artists from Vietnam, it was also an opportunity to have their work seen on the world stage. The quality of the Vietnamese artworks exhibited in Paris at this time shows how seriously they took this opportunity. For your readers, this exhibition is a rare chance to see very important Vietnamese works from private collections, as well as those held in museum collections in France, gathered together again in Asia! In parallel with this section, we also have a display titled “Spectacle and Stage” about the experiences of Asian dancers in Paris during the same period.

Gallery 2 houses the section called “Sites of Exhibition”, which delves into the diverse platforms through which Asian artists exhibited their works in Paris. This section turns to the idea of exhibition spaces, and the design has a stronger reference to the salon-type hangs in which many artists would have exhibited.

Gallery 3 is more intimate as this part deals with the social and daily lives of migrant artists from Asia in Paris, in a section called “Studio and Street”. It is quieter and more introspective as visitors reflect on the subjective experiences of being a migrant artist in Paris. In this Gallery, we also look at the end points of the period – the impact on artists of World War Two and subsequent decolonisation movements – in a section titled “Aftermaths”.

The exhibition is not comprehensive, but we hope this mapping offers visitors a rich and new perspective on the different aspects of Asian artists’ experiences in Paris.

“The show features over 220 artworks, including painting, sculpture, lacquerware, decorative arts, and a further 200 archives or archival images, in seven sections spread across three gallery spaces.”

The recurring theme of “shifting and changeable identities” is not just an issue of the 1920s-1940s. What makes this period stand out as a curatorial frame, and how do you make it relevant to the audience of this day and age?

The 1920s–1940s was a new peak of migration to Paris, so the city was more diverse than ever before. At the same time, it was a time in the history of French modern art when ideas of “French” vs. “exotic” or “foreign” were receiving a lot of consideration and debate. This made the period an especially interesting time to focus on, as this context had an impact on the experiences and careers of Asian artists. They had to navigate the expectations of a new public audience in Paris that already had certain ideas about what an Asian artist should produce, while forging their own creative paths.

Today, we still live in this globally interconnected world. So we also believe that these experiences and themes of identity, belonging, cultural exchange, creativity, and resilience will resonate with today’s audiences.

“So we also believe that these experiences and themes of identity, belonging, cultural exchange, creativity, and resilience will resonate with today’s audiences.”

The show features a wide selection of artists originating from all over Asia – with various art movements happening around the same time, blending East and West. What are some prominent commonalities among such?

One of the key features of this exhibition is that it includes, side-by-side, artists from different parts of Asia – including China, Japan, Vietnam and other countries from across Asia – in a single exhibition. This allows us to really see what common experiences they had, as well as where the trajectories of different groups diverged. Something that we noticed very frequently, regarding artists from different parts of Asia who came to Paris, was that this experience did not necessarily make their works look more “French”. In fact, for many artists, this was the period when the Asian aesthetics in their artwork intensified, as they began to reassess their heritage with the new perspective given by distance. This happened for a number of reasons: both the desire to create a new, distinctive form of modern art based on their own cultural references, as well as the expectations of the audience in Paris about Asian art. A great example is the experience of the Vietnamese artists Le Pho, Mai Trung Thu and Vu Cao Dam, who migrated to Paris in the 1930s. After migrating, their work focused much more intensively in painting on silk, with a very romantic, idealised depiction of Vietnam.

Another interesting feature brought out by the comparative framework was that artists from different parts of Asia were often exhibiting in the same places. One very popular venue for artists from Asia was the “Autumn Salon (Salon d’Automne)”, which was one of the many annual, large-scale public exhibitions in Paris in this period. Perhaps Asian artists were attracted to this Salon because it was open to artworks in both classical and modern styles. For this part of the exhibition, we sourced works by artists from Japan, China and Taiwan, all of which were exhibited in the “Salon d’Automne” of 1931.

National Gallery Singapore. Photo: National Heritage Board, Singapore.

As a Vietnamese art magazine, we are particularly interested in the Indochinese art narrative. I love how you presented art and craft in a blurred line to show the theoretical and practical dynamics of the time – many of which were informed by traditional Vietnamese mediums. What are some of your key observations on this theme?

This period was a very interesting time in the decorative arts, because of the rise of Art Deco, which was a popular, streamlined, modern style that affected architecture, interior design, graphic design as well as visual arts. What is particularly interesting about Art Deco was that it was also very exoticised and open to influences from Asia and Africa, which were fashionable at the time. Part of that influence was in the form of materials, such as lacquer, which became extremely popular in the Art Deco period.

Thinking more about modernity in the decorative arts also allows us to connect what was happening in Paris with the modern art of Hanoi. The modern lacquer painting movement was developing at the Indochina School of Fine Arts in the 1930s and early 1940s, and some early examples of Vietnamese lacquer painting were shown in Paris in 1931. But even before that, since the period immediately following WWI, Vietnamese lacquer artisans had worked in Paris in large numbers. It is certainly because of their expertise that the production of decorative lacquer in Paris could be so extensive in this period. These artisans also moved between Paris and Vietnam. So we can see that both the techniques and aesthetics were circulating between the two sites, blurring the boundaries between the fine arts and the decorative arts.

Besides the more popular names like Le Pho, Mai Trung Thu and Vu Cao Dam, it is refreshing to see that the exhibition includes other lesser-known yet important artists. What are some of your personal favourites?

Personally, my favourite part of the research for the exhibition was looking into Asian artists and artisans connected to the atelier of Swiss-born Jean Dunand, who was the leading producer of lacquer in Paris in the interwar period. He had originally been taught lacquer techniques by the Japanese artist Seizo Sougawara in 1912, but his output in lacquer hugely increased in the 1920s. I believe that this is thanks to the expansion of his workforce of Vietnamese lacquer specialists, many of whom he had started working with during WWI. Through research in the archives, I was able to show in the exhibition a list of names of the Vietnamese lacquerers who were working at the Dunand atelier in 1930. As their work often goes uncredited, it was a special moment to be able to list their names on the wall of the exhibition. Several of the workers came from known lacquer villages or lacquer-producing regions of Vietnam. Interestingly, the Javanese dancer Raden Mas Jodjana, whose work as a dancer in Paris we are also featuring in the exhibition, initially came to Paris at the invitation of Jean Dunand. Jodjana was a designer and artist in Dunand’s atelier, but we were unable to find remaining records of what specifically he made. So Dunand’s lacquer works had a lot of interesting Asian connections – Japanese, Vietnamese and Javanese! There is a lot more interesting research that can be pursued in this area.

The curatorial team has made incredible efforts in assembling a repertoire of artworks from a large number of institutions and private collections worldwide. How did the preparation go, and what were some of the biggest logistical challenges?

The exhibition includes artworks from the National Collection (Singapore) and loans from over 50 major institutions and private collections in France, Japan, Hong Kong, Korea, China and beyond. It is one of the largest groups of lenders that we have ever worked with at National Gallery Singapore. We are hugely grateful to both the institutions and private collectors who have entrusted us with these important works. For the visitor, it is a very special opportunity to see works by Asian artists from so many different places gathered together in an exhibition.

Coordinating loans from over 50 different sources is a huge logistical challenge, and we hope that the public can appreciate the diversity and the quality of the works that we were able to include. A number of public and private archives also supported us and helped to facilitate our research, and as a result we can show historical images and even moving-image footage, which is a huge contribution to the exhibition.

How has the exhibition been received by different groups of Asian audiences?

In general, I also notice that our audience is very receptive to the comparative framework of the exhibition, and interested in how artworks from their home country might resonate with those from other parts of Asia. It can be a moment for new discoveries! For me, it was very interesting to see the works of the Korean modern artist Pai Un-soung alongside Le Pho and Mai Trung Thu. There are some interesting parallels in the aesthetics.

Different sectors of our Asian audience have also naturally responded to the works by artists from their own countries. From Singapore, many visitors have been drawn to a set of works by the artist Georgette Chen, who spent much of her later life in Singapore. We are showing a group of works from her Paris period which have not been exhibited since the 1930s!

Our Vietnamese audience has been particularly delighted by the exceptional quality of the artworks on display, and the fact that this is a rare opportunity to see these works. Several come from private collections, others from museum collections in France, so it is not always easy for the Vietnamese public to see them! I hope many visitors from Vietnam will take advantage of this opportunity.

Many thanks, and once again, congratulations to the working team!

Words: Ace Lê