On an early summer morning, I had the chance to visit the timeworn yet vibrant home of Ngoc Linh. At 95, he still diligently records daily events – meals, meetings, current affairs – in his diaries. He showed me stacks of diaries he had kept over the years and proudly presented three photo books preserving 750 moments from his solo exhibition “My way”, held at the Vietnam University of Fine Arts from 25 February to 5 March 2025. He affectionately addressed me as “cháu” to his “bác”, the endearing first-person pronouns evoking a shared kinship between different generations of a big family. In this spirit, he warmly and passionately shared with me his memories of the Resistance Class – a special chapter in his youth that still burns brightly in his heart.

What led you to the Resistance Class?

In 25 years, our Resistance Class will mark its 100th anniversary. The course was a continuation of the Indochina School of Fine Arts (EBAI). It was the first official art program of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, operating in the remote mountainous area of the Viet Bac Resistance Zone. The first headmaster was To Ngoc Van. In the beginning, I worked as a nurse, having followed my brother-in-law Ton That Tung and Mr Hoang Dinh Cau to the front lines at Cu Da and Khuc Thuy in Thanh Oai, Ha Dong province. General Vo Nguyen Giap, a close friend of Tung, encouraged me to enroll in a military academy, but Tung suggested that I study medicine so I could assist him and also care for the children. Every day, I treated bomb-injured soldiers, dressing their wounds and giving injections – I became quite proficient. Seeing the patients recover made me happy, but I was also fascinated by the commanding officers. Thus, I told Tung, “I want to join the army.” So I transferred to the 5th training course for infantry officers. In 1950, I studied in Phuc Triu, Thai Nguyen, alongside Pham Tuyen and Doan Nho, until graduation. One day, while walking several kilometres to the town center on my way to Thai Nguyen, I came across a tall man sketching. I approached him out of curiosity. Seeing that I was in a soldier’s uniform, he asked, “You really love drawing, don’t you?” Turns out he was Tran Van Can. Everything was secretive during wartime, but perhaps sensing my genuine passion, Can told me about the upcoming entrance exam for an art school in Dai Tu, Thai Nguyen. Overjoyed, I asked Ton That Tung to write a letter recommending me for transfer from the military academy to the art school. So I went to Dai Tu. Looking back, had I stayed in the army, I would’ve gone to the battlefield – I had already completed all the training!

“Seeing that I was in a soldier’s uniform, he asked, “You really love drawing, don’t you?” Turns out he was Tran Van Can.”

Given the war and your military background, how did you manage to enter the art school?

The entrance exam at that time was not crowded like today. They held it in small groups – just 2 or 3 candidates per day – partly because of the war and limited mobility, and partly because applicants came from many regions. For example, Huy Hoa came from Nghe An, Ngo Manh Lan from Phu Tho. Every two or three candidates would take an exam session, each lasting two consecutive days. The exam included two parts: figure drawing and colour composition. I took the exam with Le Lam and Thuc Phi. The day before the exam, To Ngoc Van introduced the school and encouraged us, “Tomorrow you will take the exam. Professor Bui Trang Chuoc, an excellent graphic artist, will be your instructor. Try your best.” At the time, Professors Tran Van Can and Nguyen Sy Ngoc were still in Thanh Hoa; only Bui Trang Chuoc, Nguyen Khang and To Ngoc Van were present at the school. The admissions panel also included Nguyen Van Ty and Nguyen Sy Ngoc.

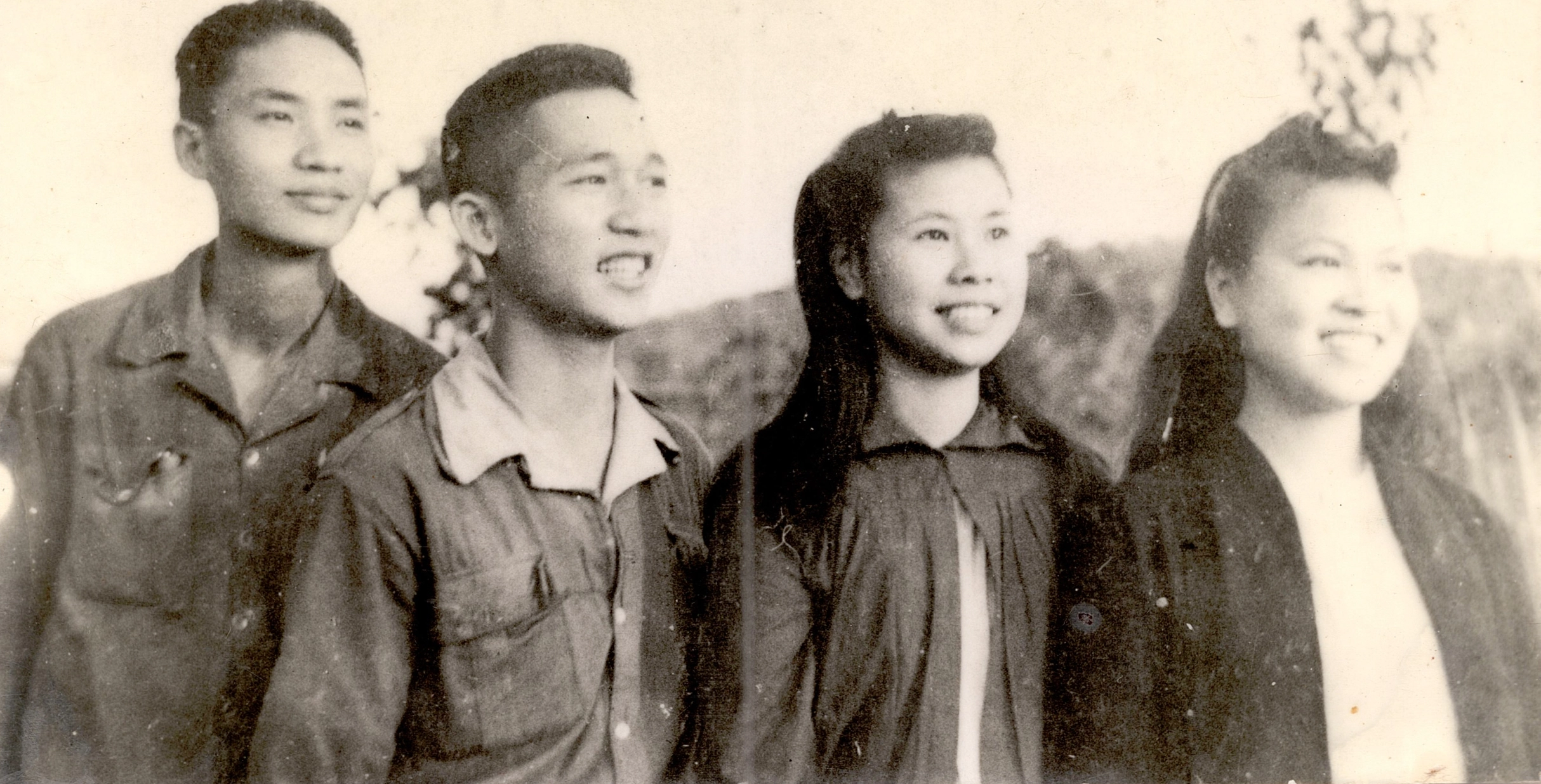

Initially, there were about 24 students; eventually, only 22 stayed. The government provided each student with 20 kilos of rice per month, and covered our food, tuition and art supplies. After a few months, the funding stopped, but I was so devoted to painting that I found ways to get by. I spent mornings in class and afternoons gathering firewood in the forest to trade with members of the Architecture Association – there were leading figures at that time like Nguyen Cao Luyen and Hoang Nhu Tiep – in exchange for rice, which I brought back to school for others as well. Some students dropped out due to financial hardship. Among the 22 students, only Thuc Phi and I had never received formal art training. Before the Revolution, I was with my brother-in-law Tung, and before that, I lived with my grandfather, Viceroy Vi Van Dinh, in Hanoi. In my childhood, I used to walk from Nguyen Du Street near Halais Lake to watch films at the August Cinema. After each film, I would ask for a program leaflet, trace the pictures, project them on the wall at night and practice drawing. Everyone in my family went into medicine or science, except me – I was the only one who took the art path. Only later did others in my family follow in my footsteps.

What was it like to study under wartime conditions? How did the teachers guide students?

Because of the war, the school had to relocate constantly – from Tuyen Quang to Yen Binh to Phu Tho. The professors included Tran Van Can, To Ngoc Van, Nguyen Khang, Bui Trang Chuoc, Nguyen Sy Ngoc, Nguyen Van Ty, Nguyen Tu Nghiem. We all lived among the villagers and studied under stilt houses. We did not use formal titles – teachers and students treated each other like family members. Every week, there would be assignments in decoration, figure drawing and landscape. Bui Trang Chuoc mainly taught decorative drawing. All teachers were involved in figure drawing. Unlike EBAI, we did not draw nudes due to wartime conditions. Our model was Ms Hue, who had been To Ngoc Van’s regular model since before the war. She continued to model for us, alongside our supply officer Vung and even village elders like Mr Dao. Often, students took turns modeling for each other – Dao Duc drew Le Lam and vice versa. It was wartime, so we improvised. For field sketches, we would go out in groups after the morning flag raising ceremony, wandering into villages. The teachers would follow behind, sketching landscapes, reviewing our work and offering guidance. It was a lot of fun in our course. Aside from drawing, we also helped the locals with farming and milling. They loved us, and they would even save eggs just for us. The teachers were incredibly dedicated. Nguyen Tu Nghiem brought several books on European masters like Gauguin, Matisse all the way to the Resistance Zone to share with us. Dao Duc and Trong Kiem loved Gauguin, while Luu Cong Nhan preferred Monet.

And how were assignments graded?

Each week, students would hang their drawings on strings with bamboo clips under the stilt house for review. One student would be assigned to rank all the other 21 (and themselves) and explain their reasoning based on composition, colour, form, or interesting discoveries. The teachers would listen. It was a great way for us to develop critical observation. Everyone took turns.

Could you tell us more about your course’s exhibitions during the Resistance period?

Our class was skilled at both sketching and making propaganda posters. During the war, we would travel to markets in Lao Cai and Yen Bai to exhibit our works for the local communities. The posters encouraged farming, joining movements, paying taxes and donating rice to the government – all to explain the government’s policy of temporarily loaning the spring harvest.[1] Villagers came in large numbers to see our works. In late 1951, our entire class traveled to Lao Cai and Yen Bai to paint and prepare for a fine arts exhibition. Artists like Quang Phong, Duong Bich Lien and Nguyen Sang also joined – they hadn’t finished their studies when the Revolution broke out, so they came to meet To Ngoc Van to take their graduation exams. The exhibition featured works by Phan Thong, Nguyen Quoc An and many others. The response was overwhelming; the atmosphere was solemn. I submitted a painting depicting people carrying rice for tax contributions. It was a special day – Deputy Prime Minister Pham Van Dong, Education Minister Nguyen Van Huyen and Acting Interior Minister Phan Ke Toai also attended. President Ho Chi Minh even sent a congratulatory letter encouraging the artists and congratulating the exhibition. After the war, the Resistance Class held four exhibitions. I helped organise every single one. The 1954 show was at the Exhibition House on Trang Tien Street. The next two were at No. 16 Ngo Quyen Street. For the last one in 1993, I secured funding from the Sweden–Vietnam Cultural Development Fund on Tran Hung Dao Street to print a catalog at Tien Bo Printing House.

“During the war, we would travel to markets in Lao Cai and Yen Bai to exhibit our works for the local communities. […] The response was overwhelming; the atmosphere was solemn.”

Looking back at your lifelong journey in the arts, what is the guiding principle that you have always held on to?

I remember what To Ngoc Van said at our graduation: wherever you are assigned to, use art to serve the people. The people give you food and clothing; you must give back through painting. Create works they can understand and appreciate. Love art, love your craft and devote yourself to your calling. His heartfelt message has stayed with me all my life.

Words: Tâm Phạm

Translation: Lưu Bích Ngọc