Greetings! Could you share with us the moment you discovered the Hue kite at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in the United States?

When visiting the laboratory of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum (NASM), I learned that the institution operates two facilities: one located in the centre of Washington DC, and the other in suburban Virginia – which houses a storage facility and primary conservation lab. I was quite curious as I work in the field of art conservation, and since such tours are quite common, including exchanges with visiting specialists, I arranged a visit. While touring the lab, I was surprised to come across a Vietnamese flag and a kite. The flag of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam was nearly fully restored. However, it was the kite that truly caught me off guard – it was enormous and took up almost the entire surface of a table. Its shape was highly distinctive and it was made of a rather peculiar kind of paper. I shared with the staff my deep interest in these artifacts, especially as there is a growing movement in Vietnam focusing on researching and reviving traditional toys. I told them this kite was truly special and that I had never come across such a collection in Vietnam. I proposed a plan to study it further, with the hope to share my findings with both the Vietnamese public and the academic communities. I also expressed a desire to trace the kite’s journey from Vietnam to the United States.

Initially, I was drawn not only to its structure but also to the story behind it. With the help of archivist David Schwartz and curator Caroline, I discovered two letters between Colonel Robert C. “Bob” Mikesh, a US Air Force officer stationed in Hue, and Paul E. Garber, former curator of the Smithsonian. One day, during a flight, Mikesh spotted what appeared to be birds flying through the sky. But as he flew closer, he realised they were kites. Captivated by the sight, he wrote to Garber about bringing one back to the US for the museum’s collection. He later commissioned a local kite artisan in Hue and built a wooden crate by himself for transport. Unfortunately, the crate was left out overnight in the rain at Da Nang Airport and the kite’s tail absorbed water, becoming misshapen. I came across archival photographs showing the tears. In his letter, Garber pondered how to restore them. During the restoration process, we chose to leave the old tape in place as part of the object’s story, a quiet part of history. The kite must have been hung in Garber’s office for a while before falling into obscurity for almost 60 years, until my chance re-discovery.

A kite is never meant to last. It is crafted, takes flight and usually meets the end through some inevitable mishaps – especially with traditional ones made from dó paper, bamboo, and wood rather than the industrial materials used today. What kind of journey has this kite been through to survive to this day?

As the question suggests, traditional kites are typically made from dDo paper, bamboo, and wood. In fact, when I was a child, I remember seeing kites made from newspapers. But this kite wasn’t crafted from traditional materials but modern ones. As a painter and an art practitioner, I believe artisans and artists alike are always searching for better materials. The use of industrial materials doesn’t necessarily mean falling into a rut; in fact, it can be seen as an upgrade for contemporary kites.

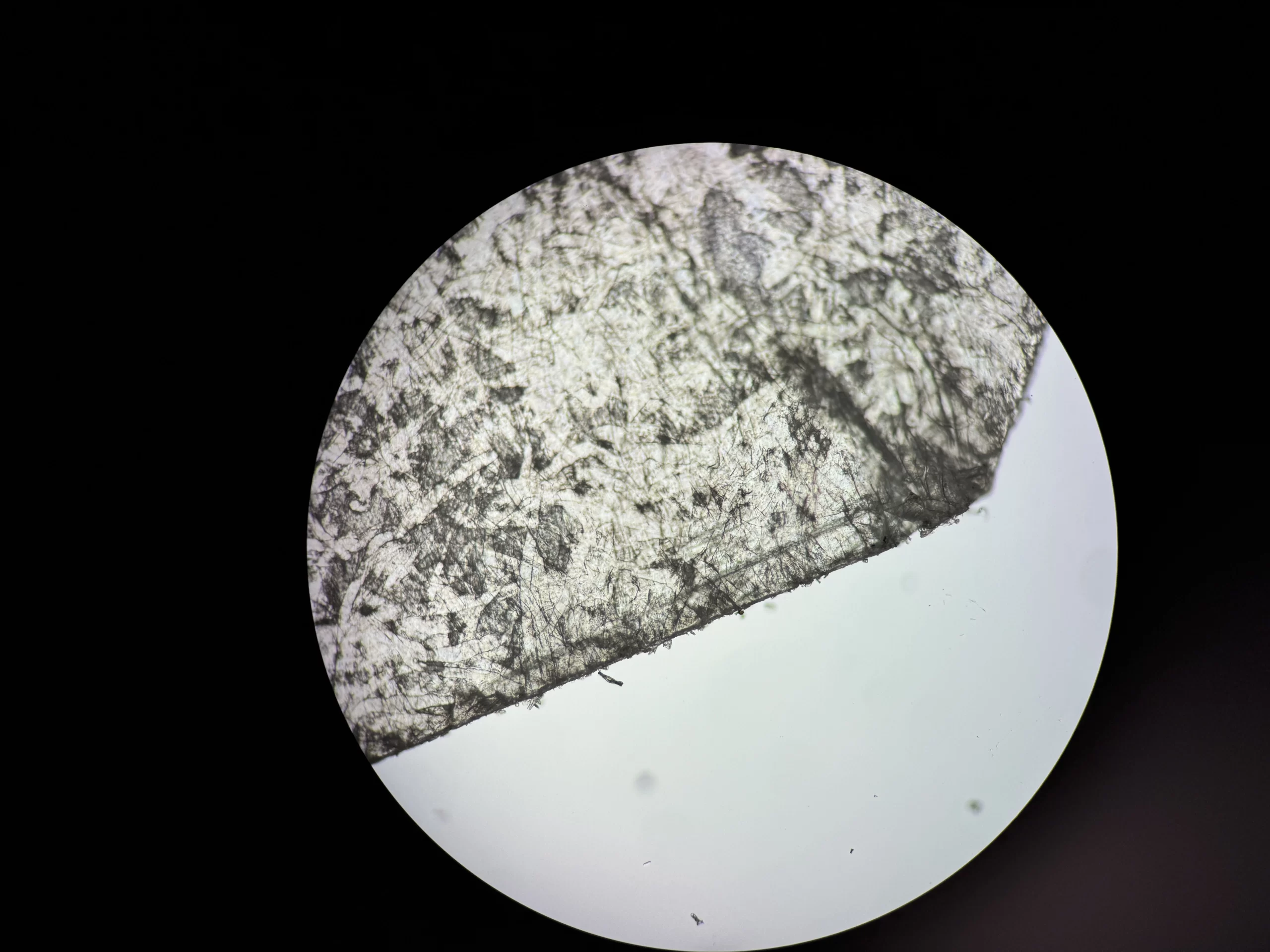

What makes this kite truly stand out is that it was made from glassine paper – a modern material with a specific gloss and remarkable durability. It is partially water-resistant and more durable than regular paper. Its surface resembles that of wax paper or candy wrappers – a meaningful technical refinement on the part of the artisan. He understood that the customer was a foreign pilot, someone about to embark on a long journey back to the United States, and thus he poured great care and intention into making the kite. He even added nylon strings and wrapped foil around the tail to create a shimmering effect as it danced through the air. I believe that through deeper discussions with kite experts, we can explore the aerodynamic aspects of this design even further.

What level of technical expertise and facilities were required for the restoration work carried out by you and the team, compared to international standards and those currently available in Vietnam?

First of all, the Smithsonian’s Museum Conservation Institute is among the best in the world in terms of infrastructure. It is a vast space, large enough to house several Boeing aircrafts, yet it maintains 50% humidity and 21°C continuously round the clock – an extremely costly standard that only major museums can afford to uphold. In addition, they have storage facilities designed specifically for different types of artefacts. The majority of items are preserved at 16.6°C and 40% humidity. This level of investment in preventive conservation significantly reduces conservators’ while maximising artefacts’ lifespan. At NASM’s conservation unit, art conservators aren’t alone – it’s a collaborative effort involving aerospace engineers and NASA specialists. Therefore, it’s not surprising to find that many retired instruments and technologies from NASA would find a second home here.

In terms of analytical equipment for conservation, there are X-ray imaging machines to analyse structural layers, various types of polarising microscopes, and FTIR instruments. The imaging setup includes not only standard lighting but also ultraviolet light. The Smithsonian also collaborates with the Museum Conservation Institute, which brings together experienced scientists and conservation experts. There, even more advanced equipment is available for complex tests ranging from DNA analysis, CT scans, Py-GCMS, hyperspectral cameras, to XRF scanning and mapping.

In terms of human resources, one must go through a long training process to become a professional conservator in the US: it typically takes 10–15 years of formal training from undergraduate studies, internships, to master’s and doctoral programmes. In the US, there are only four universities offering master’s programmes in art conservation and fewer than 30 students graduate each year, making the field extremely competitive. In Vietnam, this field has yet to be formally established. That’s why I’ve always hoped to bring back what I’ve learned in the US and contribute to the development of conservation training at home. To me, conservation is like a “three-legged stool” balancing sciences, arts, and skilled craftsmanship. It serves as a key to connect the past and future, preserving not only historical objects but also cultural links, as well as stories of techniques and materials that are in decline.

The complete restoration of the Hue kite allows it to continue its life halfway across the world from its birthplace, more than half a century later, right at the 30th anniversary of diplomatic relations between Vietnam and the United States. What did this journey mean to you?

While working with the artefact and reading through archival letters, I felt deeply the care and sincerity from both the kite maker and the recipient. Mr Garber wrote several times to the artisan and his family, especially after the 1968 Tet Offensive. However, he never received a reply, which made him even more concerned about their safety during and after the war. As I followed the archival trail, I discovered a number of gaps – particularly the absence of any address or contact information of the kite maker’s family in the records. With the help of archivist David Schwartz, after combing through several large cartons of documents from 1967–1968, we were fortunate to find some answers to the lingering questions surrounding this kite.

At the time, I knew the search wouldn’t be easy – after the 1968 Tet Offensive, the city of Hue suffered heavy damage, and after the reunification, many street names had changed. I reached out to Mr Ace Le from the Lan Tinh Foundation, who had just organised an exhibition of Emperor Ham Nghi’s paintings in Hue, to ask for help. He connected me with Nguyen Duc Niem, a young artist, and to my surprise, Niem managed to track down the exact old address. He didn’t just search in the city but even turned to YouTube and discovered that the street once called Vo Tanh is now Nguyen Chi Thanh Street. Eventually, he managed to locate the kite maker’s family home, which has since become an ancestral house, and met the artisan’s granddaughter.

I feel fortunate and deeply moved by this story, one that I’m eager to share with people in both Vietnam and the US, especially on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of diplomatic relations between two countries. In one of his letters, Mr Garber recalled a kite lecture where he said that if, instead of war, soldiers from both sides had flown kites together, then “our boys could go home.” He added that the entire room broke into applause, and reading that made me feel as though I was right there with them. We can see this story as one not only about art conservation, but also a historical testament between two nations, a symbol of peace, like kites soaring freely in the sky.

My final question is whether you feel confident that this “little bird” will be able to spread its wings and fly high in both American and Vietnamese skies?

Many people have asked me whether the kite could still fly after being restored. But it’s a bit like asking if a royal throne, once damaged and repaired, can still be sat on. From a conservation standpoint, a museum artefact no longer serves its original function. That’s why no one dares to fly this kite, because it’s far too fragile now. Still, Mr Garber once expressed his wish to witness the kite in flight. He even suggested sending a roll of film for Colonel Mikesh to record the moment it would soar, showing how the tail would flutter, the silver paper shimmering, and the kite’s body trembling in the wind.

I hope that with the materials and documentation we now have, we can collaborate to recreate a replica of the kite in Vietnam. We could then film it flying and send the footage back to the museum as a meaningful extension of the artefact. That would be a beautiful continuation, watching the kite take flight once more in Vietnam, and perhaps even in the US, as a symbolic journey of peace, freedom, and remembrance.

Thank you for your sharing!

Words: ChuKim

Translation: Thu Huong