Junquo Nimura (b. 1970) is a Professor at Kwansei Gakuin University, Japan. After studying art history at the University of Paris IV, she lived in Shanghai between 2004 and 2007, before obtaining her MA and PhD from the University of Tokyo. Her book “The History of Modern Vietnamese Art: The Half-Century under French Rule” came out in 2021, marking the first time a book on Vietnamese modern art history was published in Japan. Prior to this, the Japanese public had only ever encountered Vietnamese modern art through exhibitions. In this exclusive interview*, the author shares with us the process of developing the book and her plans to bring the publication to a broader audience in the future.

(The interview was originally conducted in Japanese)

Good afternoon, Prof Nimura. What aspects of the research did you particularly focus on?

First, an interesting point that had not been previously noted was that in studies of modern Asia, the boundary between “美術” (fine art) and “非美術” (non-fine art) remained rather ambiguous. This problem isn’t limited to Japan; studies on China and Vietnam also encountered the same issue. Previous scholars often used the term “美術” as if it were already well-defined. So I started by systematically unpacking and re-defining this terminology. I found the emergence of the term “美術” to be very significant, as it highlights the cultural connections between Japan and other Asian countries.

“In studies of modern Asia, the boundary between ‘美術’ (fine art) and ‘非美術’ (non-fine art) remained rather ambiguous.”

My second area of focus was Japonisme[1].

While I wasn’t particularly interested in this topic as a Japanese person, I found it fascinating how Japonisme, which had been extremely popular in late 19th-century France, was later introduced to Vietnam by the French. The word “kakemono” (Japanese hanging scrolls) actually shows up in the Governor-General of Indochina’s administrative documents. Furthermore, French artists who grew up during the peak of Japonisme in Europe later taught at the Indochina School of Fine Arts. These discoveries had not been made previously.

[1] Japonisme or Japonism refers to the influences of Japanese aesthetics, culture and visual arts on Western European society and art from the mid- the late-19th century, especially in France, England, and The Netherlands.

Additionally, there were also Japanese lacquer teachers working in Hanoi in the 1910s, namely Ishiko Suehiko and Ishikawa Kōyō, who was a casting instructor, but apparently also taught lacquer work. They’ve been largely ignored by scholars. Given the limited research available on them, I have prioritised them in my work.

In your book, you discuss at length Pham Quynh, who pioneered the systematic use of the term “my thuat” in his writings, starting with articles around 1914. You argue that nearly two decades after, it was Nam Son’s essays on “my thuat” that helped shape the concept as it is understood in Vietnam to this day. Is this the main argument of your research?

Yes, I started by investigating how “my thuat” was understood in Vietnam before 1925, primarily through Franco-Vietnamese and Sino-Vietnamese dictionaries. Tracing back to the 1880s, I discovered people were experimenting with different translations of this concept. Pham Quynh’s 1914 article marks what I consider to be the first widespread use of “my thuat” (initially spelled “mi thuat”) in Vietnamese society. Of course, as research progresses, we might find even earlier instances.

You have been very thorough in your research and analysis of the boundary between “fine art” and “non-fine art”. I’ve noticed academia is increasingly interested in studying concepts that straddle ambiguous boundaries. What would you say is driving this trend?

By examining French colonial administration documents, I discovered that they placed a significant emphasis on arts and crafts. While painting and sculpture were regarded as high art, the colonial administration actually invested more in what they considered “non-fine art” – crafts that, although not classified as fine art, held commercial value. France showcased Indochinese handicrafts alongside industrial products at international expositions. Therefore, we need a more realistic approach to studying Vietnamese art from this period. We should ask: what were the French, with their successful industrial economy, truly trying to accomplish in Vietnam?

“I found the emergence of the term ‘美術’ to be very significant, as it highlights the cultural connections between Japan and other Asian countries.”

Since its publication, how has your book been received in Japan?

I’ve been able to connect with researchers who share similar concerns. Vietnamese sociology scholars in Japan found it particularly interesting. I also received positive feedback from researchers outside the art field, including sociologists, cultural anthropologists, and comparative literature scholars whose research focuses on Africa and colonial studies. Additionally, I was awarded the UTokyo Jiritsu Award for Early Career Academics in 2020, and the Kimura Shigenobu Award from the Japanese Society for Ethno-Arts in 2021.

Perhaps due to its nature as a comparative culture research, despite focusing on art, your book provides such a comprehensive analysis from multiple perspectives on linguistics, institutions, and society. What originally inspired you to study Vietnamese modern art history?

When I was younger, I was captivated by Western art philosophy. As I matured, however, I found myself increasingly drawn to Asian art, particularly the modern art of East Asia including Japan, China, Korea, Mongolia, and also Vietnam. In 2004, I began living in Shanghai, which deepened my interest in Chinese art, especially from the Republican era. During this time, I became fascinated with the painter Sanyu and wrote my master’s thesis on him. Since I had also studied in France, I was fortunate to be able to access French archival materials on Asian artists who had connections to France. In contrast to the Anglophone academic community, very few researchers were utilising French-language sources related to Asian art. This represented a research gap I could help address.

“French artists who grew up during the peak of Japonisme in Europe later taught at the Indochina School of Fine Arts. These discoveries had not been made previously.”

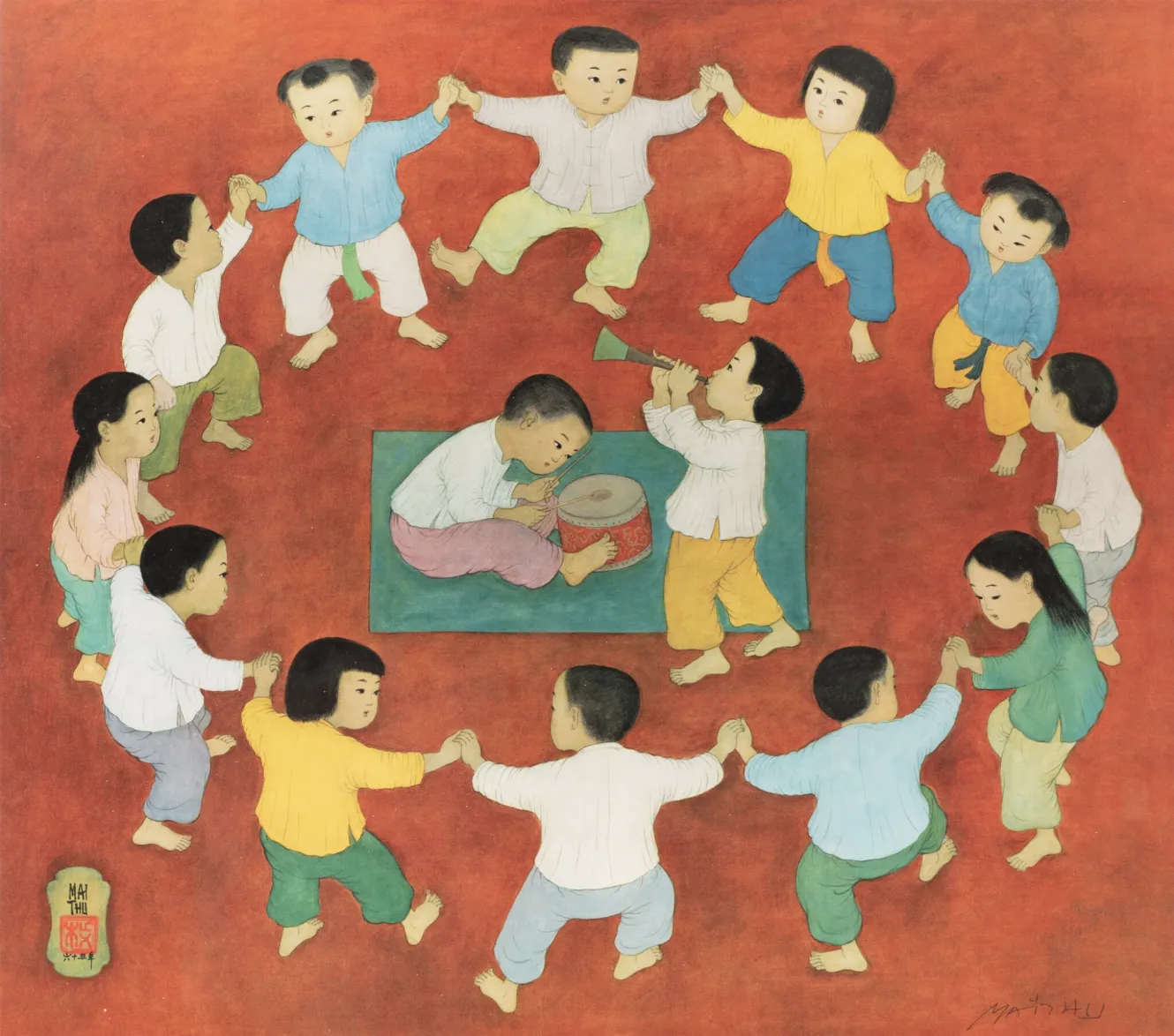

As a matter of fact, before starting my master’s program, I was working and happened to meet the families of artists like Mai Trung Thu, Le Pho, and Vu Cao Dam. This experience became a turning point that inspired me to delve deeper into Vietnamese art.

How did you come to meet these families?

They had been friends of my husband’s for decades. Another factor that led me to this research was a trip to Morocco for a writing job where I was interviewing people who lived in interesting architectures. The person I interviewed happened to be Vu Cao Dam’s son, and when I heard that his father was a painter, I looked up his work and reckoned, “This is a really special part of Vietnamese art history.”

Around the same time, art historian Nadine André-Pallois had just published a paper on the discovery of a large amount of Vietnamese archives at the Overseas Territories Archives Department in Aix-en-Provence, France. Previously, Vietnamese art had only been primarily discussed by collectors rather than academics. Her discovery really inspired me to approach Vietnamese modern art history from a more scholarly perspective.

So it wasn’t research that led you to meet these artists’ families, but rather personal connections that led you to the topic. I’d like to hear more about your PhD journey.

After completing my master’s thesis, I discussed my doctoral direction with my advisor and he was very encouraging in that, “The topic of Vietnamese art will definitely be fascinating.” Back then, I was juggling between work and study, and shortly after submitting my master’s thesis, I discovered I was pregnant. My advisor suggested I use my maternity leave to learn Vietnamese, as it would be helpful for my doctoral studies. To be honest, I questioned whether it was even possible for me to research Vietnamese art without knowing Vietnamese. In fact, I was considering switching to researching the Japanese painter Nakamura Fusetsu instead. However, other professors also motivated me, saying, “You know French, English, and Chinese, that’s your unique strength.” Their words motivated me to commit to researching Vietnamese modern art. Even then, the first three years of my doctorate were spent solely on reading existing research.

What challenges did you encounter during your research?

The first three years of my journey were incredibly challenging. I had left my job to pursue my PhD, which put a considerable strain on my finances. Just when I was reaching a point of physical and mental exhaustion, I received a grant from Sumitomo Life for female researchers. With this funding, I could afford childcare, freeing up the time I needed to focus on my research. It was an absolute lifesaver and my research truly took off from there.

At the University of Tokyo, where I studied, PhD students typically took an average of 8 years to complete their theses – the maximum time allowed, at least according to data from about six years ago. The lengthy duration was due to the university’s goal which emphasises on candidates not just obtaining a degree but producing works of award-winning quality. I also took about that long to complete my thesis.

Another issue is that Japan lacks a suitable framework for presenting new research. An unprecedented or unconventional research won’t be easily accepted. The major art history conferences in Japan tend to be quite conservative. They kept rejecting my paper, claiming that there were no specialists in the field available to assess it.

Indeed, breaking new grounds in Japan is never easy. What are your plans for future research?

I am currently researching the artistic exchanges between Japan, France, and Vietnam from 1940 to 1945. During this period, Governor-General Decoux implemented policies on crafts. In addition, Japanese Cultural Centres where both craft and fine arts projects were carried out. Charlotte Perriand emerged as a key figure in these interconnected cultural initiatives involving the three countries. I hope to share these discoveries with readers shortly.

Thank you so much for sharing your fascinating journey with us! We’re excited to see what your future research brings.

Words: Masuda Hikaru

Translation: Hà Châu Bảo Nhi