Nam Son, born Nguyen Van Tho (1899–1973)1, is regarded as one of the founding figures of modern Vietnamese art. He was a co-founder and core instructor at the Indochina School of Fine Arts. Born into a Confucian family in Hanoi, Nam Son exhibited a precocious talent for painting and was mentored by Confucian scholars such as Pham Nhu Binh and Nguyen Si Duc, whose instruction in classical learning and aesthetics instilled in him a deep reverence for the national culture. In the absence of a formal art education in Vietnam at the time, Nam Son was largely self-taught, studying traditional folk painting alongside Chinese and Japanese art. This eclectic foundation contributed to the formation of a distinctively Eastern visual language. While working at the Agence Économique de l’Indochine, he continued to pursue his artistic practice and illustrated books by scholars such as Do Than and Tran Trong Kim. His chosen pseudonym, “Nam Son (Southern Mountain)”, connoted steadfastness and became synonymous with his artistic identity.

Greetings, Monsieur Khoi! After decades of research and debate, it is only recently that Master Nam Son has been rightfully acknowledged as a co-founder of the Indochina School of Fine Arts (EBAI). And you have been one of the most prominent voices. Could you share with us a brief overview of this journey?

I have dedicated over two decades to restoring the rightful place of Nam Son in Vietnamese art history. This journey has been not only an academic pursuit but also an emotionally resonant endeavour, marked by unwavering efforts to uncover and examine valuable archival materials, especially those kept in overseas archives. At the Overseas Territories Archives Department in France, I located many key documents. More significantly, at the National Institute of Art History in Paris, I gained access to the extensive “Victor Tardieu” archival fonds. This collection, numbered 125 under the “Jacques Doucet” catalogue, comprises thirteen cartons of rich materials documenting the life and career of Victor Tardieu, including personal papers, correspondences with family, friends, colleagues, and students, as well as photographs and notes on his artistic life. A substantial portion of this collection pertains to EBAI and offers vivid insights into the school’s founding and development. In addition, the press archive at the National Library of France holds a wealth of valuable articles, essays, and documents concerning the cultural and artistic life of the era. In parallel, the Nam Son family’s private archive has provided a more intimate and personal perspective, enriching my comprehension of the personal and emotional world of my “artist grandpa”.

Indeed, Nguyen Nam Son is the rightful co-founder of the Indochina School of Fine Arts. This journey is not simply a matter of fair recognition, but an assertion of Nam Son’s indispensable role in the founding of modern Vietnamese art. In a book published by the Governor-General of Indochina in 1937, which comprises writings and annual reports submitted by Tardieu to the colonial authorities, Nam Son was explicitly named as a co-founder of the school. Such official acknowledgement was based on Nam Son’s tangible contributions. If his role had been limited to that of an “assistant” as some commentators have suggested, would the colonial administration have formally honoured him in such terms? Before the establishment of EBAI, Nam Son had already been working closely alongside Tardieu. This collaboration was instrumental in helping Tardieu gain a deeper understanding of Vietnamese art and in shaping both the curriculum and the selection of the first cohorts. During the school’s formative years, Nam Son directly taught the preparatory classes, an essential foundation for cultivating Vietnam’s pioneering generation of painters. Such responsibilities cannot be regarded as only “auxiliary” since he did directly play a formative role in shaping the career trajectories of generations of masters.

“During the school’s formative years, Nam Son directly taught the preparatory classes, an essential foundation for cultivating Vietnam’s pioneering generation of painters.”

“During the school’s formative years, Nam Son directly taught the preparatory classes, an essential foundation for cultivating Vietnam’s pioneering generation of painters.”

French painters came to Vietnam to not only establish and teach at the schools of fine and applied arts, but also learn from indigenous techniques and materials. What role did Nam Son play in transmitting such knowledge and methods to the French, and subsequently, Vietnamese students?

As a pioneering artist and co-founder of EBAI, Nam Son had left an enduring mark on Vietnamese art education, guided by a strategic outlook. Before the school’s formal establishment, he authored a proposal titled “Vietnamese Fine Arts”, in which he suggested the creation of a university-level institution to train artistic talents and preserve traditional art foundations while reforming and architecting an art style that is uniquely Vietnamese. This proposal did not merely reflect reformist thinking; it served as a guiding framework for the future development of modern Vietnamese art.

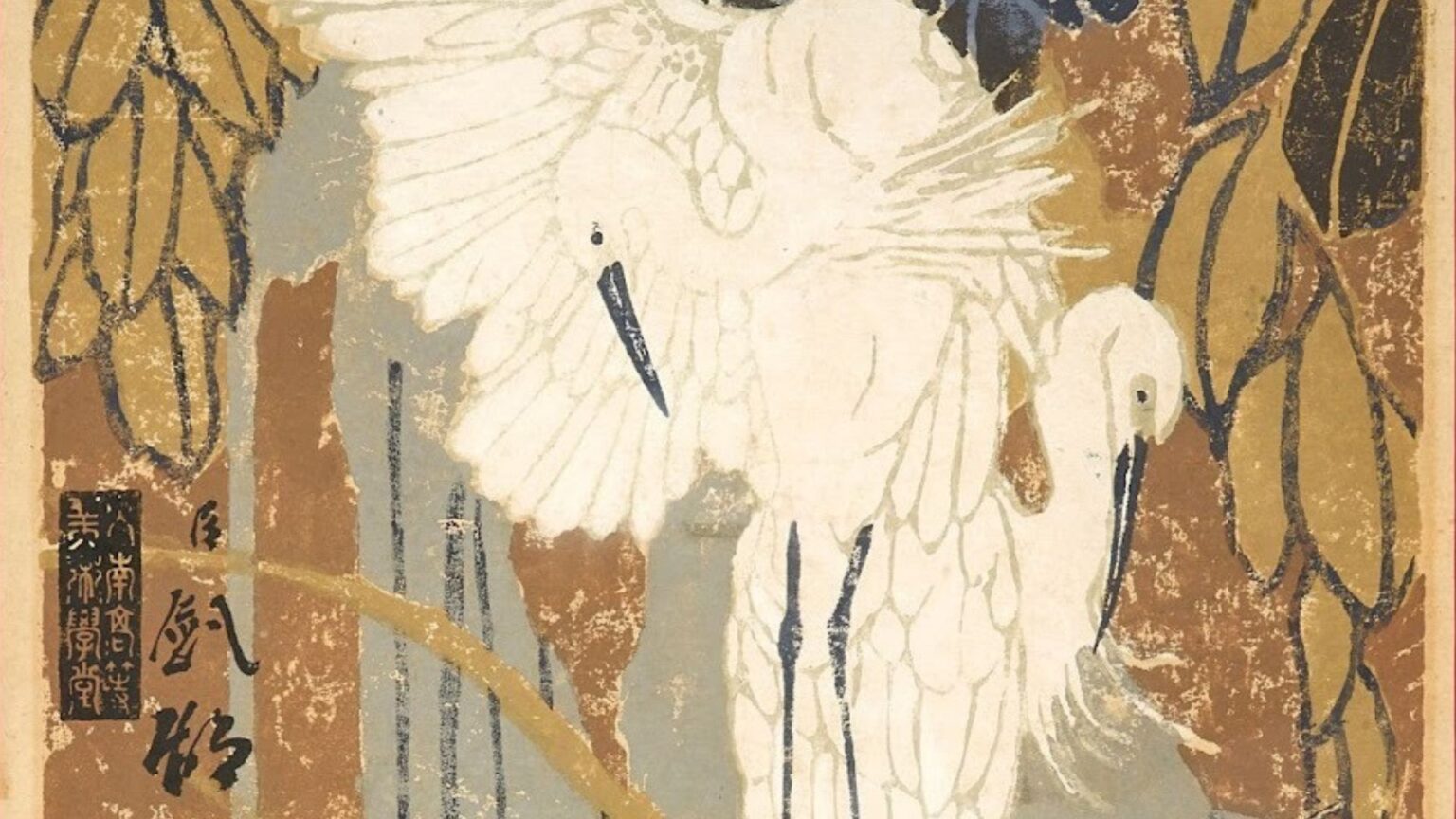

Nam Son had introduced French artists – including Tardieu – to traditional Vietnamese techniques, particularly lacquer painting, an art form with over 2,500 years of history. He shared with them traditional knowledge about the usage of resin from lacquer trees, methods of polishing, and the blending of colours to produce works of exceptional aesthetic quality. The concept for the Vietnamese Lacquer Department – the precursor to the Lacquer Painting Department at EBAI – was initiated by Nam Son himself, who had exposure and extensive familiarity with this traditional medium. In his role as an educator, Nam Son was responsible for the preparatory class, where he instructed students in drawing, painting, silk painting, lacquer design, engraving, decorative art for painting and sculpture, as well as ceramics. As a dedicated teacher, he actively encouraged students to explore local materials such as lacquer, silk, and woodblock printing. At the same time, he guided them in adopting modern painting techniques, bridging traditional Vietnamese art with modern practices. Nam Son’s teachings were not merely inspirational; they actively led students to approach art with refinement, creativity, and a deep reverence for Eastern identity. His “Vietnamese Fine Arts” proposal also underscored the importance of preserving traditional arts through the collection of works, the establishment of museums, and photographic documentations. In particular, he advocated for the use of techniques to archive and document historical relics, such as “croquis coté”, “relevé archeologique” and “moulage”2. He further proposed the creation of specialised departments to compile a dictionary of fine arts, translate books and develop a library housing both Eastern and Western resources, with a special emphasis on those from the East. Several archival documents reveal the long-term vision of Nam Son. He outlined an educational orientation for the school rooted in Eastern aesthetics, seeking to overcome the problem of disproportion often found in traditional Vietnamese art. His approach combined the Western realist tradition with the expressive brushwork of classical Eastern painting. He proposed a curriculum structured around seven departments: Painting (including calligraphy, Western realism, and Eastern-style painting), Architecture, Sculpture, Vietnamese Lacquer, Decorative Arts, Engraving, and Painting Mounting. Each division was designed to preserve and revitalise the nation’s artistic heritage.

Nam Son’s blueprint extended beyond pedagogy to include plans for the development of a national museum of fine arts, the restoration of ancient architecture, overseas study programmes, and the publication of art books and periodicals. He stressed the need to send talented students abroad, to invite distinguished foreign instructors to Vietnam, and to establish dedicated libraries, journals, and specialised newspapers to support the dissemination of artistic knowledge. With this comprehensive vision, Nam Son expressed his conviction that in 10–30 years, Vietnamese people could cultivate a flourishing and distinctive cultural identity.

Nam Son was a humble and quiet person, yet he had vision and great depth in his research. He was also the first Vietnamese scholar to publish a monograph on painting, on Chinese art to be precise. This marked a significant milestone in both the history of Vietnamese fine arts and the development of academic publishing in the country.

His monograph “Chinese Painting: Techniques and Symbolism – The Unique Chinese Way of Interpreting Nature” was published on the 31st of the first lunar month of 1930 and could be considered the first book on painting written and published by a Vietnamese author. More than a study of Chinese aesthetics, it was a declaration of artistic vision for Indochina, an invitation for Vietnamese painters to root their creativity in Eastern identity. As Luu Cong Nhan later observed, the spirit of Eastern nationalism and cultural pride evident in the works of EBAI artists owed much to Nam Son’s intellectual leadership. By situating Chinese painting within a broader context of cultural confluence, Nam Son had laid the conceptual groundwork for the emergence of modern Vietnamese art. His publication marked a moment when Vietnamese intellectuals began to assert their voices in the realms of art criticism and publication.

Nam Son concluded that although Chinese painting possessed many aesthetic merits, it had stagnated due to a lack of dynamism and innovation. “All things must progress in life. That is the law,” he wrote. The book, whose cover and decorative borders were illustrated by Nam Son himself, was published in a limited edition. Prof Dr De Fenis, in a review published in L’Avenir du Tonkin, remarked, “The limited edition, along with the cover illustration and ornamental borders, elevate the book’s artistic value. It will undoubtedly arouse no small curiosity among lovers of fine literature.” The work also garnered attention when it was featured on page 301 of issue 32 of the “Economic Bulletin of Indochina”, affirming its scholarly and cultural resonance at the time.

You are currently completing a major publication on the life and career of Nam Son. Could you share more about this ambitious project?

I have devoted over a quarter of a century to the making of “Nam Son – The Artistic Legacy of Indochina, through Archives, Press and Personal Records” – an earnest endeavour to restore and reframe the memory of one of the founding figures of modern Vietnamese art. This is not simply a biography. It is an effort to re-position the important role of Nam Son in Vietnamese art history, especially on the occasion of the centenary of EBAI. The project began in 1999, driven by a paradox: few outside academic circles in Vietnam knew his name, while in France, Nam Son was remembered with reverence. That dissonance sparked my resolve to delve deep into archival shadows to recover what had been obscured by the tides of history. My goal is not to tell a personal story about Nam Son, but to retrieve an important part of Vietnamese art history through his lens. The book unfolds chronologically, tracing Nam Son’s life from his earliest days and youthful passion for painting, through his meeting with Tardieu, his study at Paris College of Fine Arts, to his pioneering role in shaping Indochinese art. I have long aspired to compile a catalogue raisonné of his works. Alas, many of his paintings are dispersed worldwide, and several in Hanoi remain beyond my reach. Thus, the catalogue remains an unfinished dream. Still, I have tried my best to ensure that all information presented is grounded in rigorous documentation, with clear and careful annotations, to present an objective and trustworthy viewpoint.

“My goal is not to tell a personal story about Nam Son, but to retrieve an important part of Vietnamese art history through his lens. “

Though imperfect and incomplete, this book marks the beginning of a longer journey, one I am committed to supplementing and completing. As we commemorate the centenary of the EBAI, I hope this publication will serve not only as a tribute to my maternal grandfather, but also as an invitation to readers of Art Republik to discover and cherish the legacy of Nam Son. I must express my deepest gratitude to Nam Son, who, like myself, was born in the Year of the Earth Pig – 60 years apart. In some inexplicable way, I have always felt his presence like an invisible hand guiding me towards archival treasures I once thought had been lost to time, revealing a life I had never known, and helping me bring this work to light.

In the current art scene that remains heavily Eurocentric, your efforts are valuable and essential. Thank you and wish you all the best in your project!

Words: Ace Lê

Translation: Hùng Nguyễn