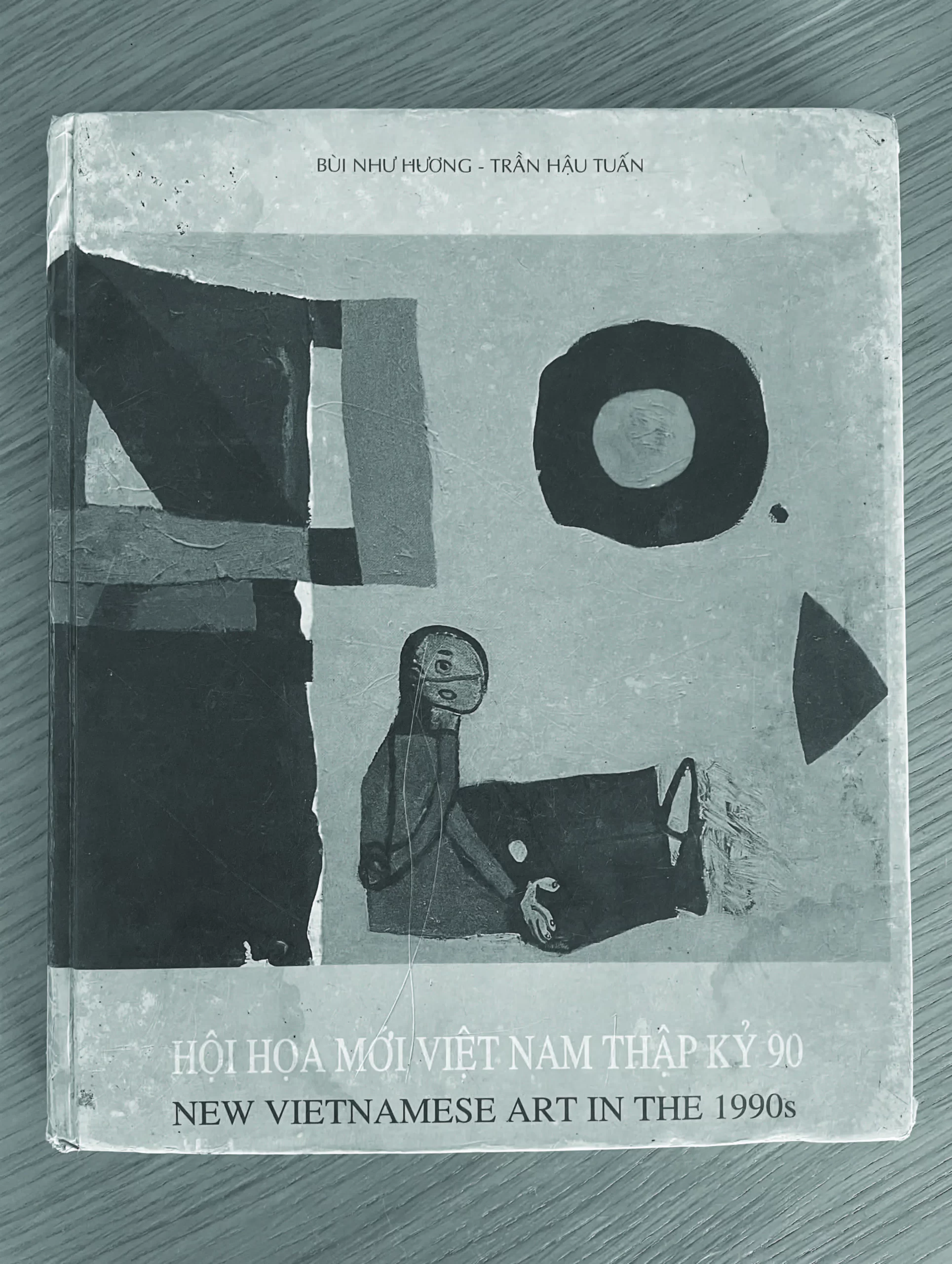

Good afternoon, and thank you for accepting our interview request. Can you recount the process of making the book “New Vietnamese Painting of the 90s” (2001) with co-author Tran Hau Tuan?

The 90s was a period of creative flourishing in the Vietnamese art scene, after many years of being restrained by wars, isolation, and backwardness in artistic thinking. While before in schools, there existed mainly the style of Socialist Realism mixed with Impressionism, now, everything has changed. We can identify a few noteworthy trends such as: giving up school-taught techniques to return to an instinctive painting style; relearning folk art (mainly in villages’ communal house); exploring and improvising the language of art through materials, mediums, and schools of expression (with influences of Western art from the distance).

If the first half of the 90s only witnessed the modernization of painting in terms of the content on canvas, the second half even saw bolder and more extreme shifts in artistic concepts and forms. These changes can be seen as efforts to catch up with the global stream of contemporary art.

The artistic atmosphere and creative spirit of the 90s was so captivating that we wanted to selectively record it as a “diaristic inventory”, so it wouldn’t fall into oblivion. That’s why “New Vietnamese Painting of the 90s” was born. There was so much to do, including documentation, writing, illustration, translation, printing; all demanded accuracy and aesthetics. I was fortunate to cooperate with Tran Hau Tuan to reach the final result.

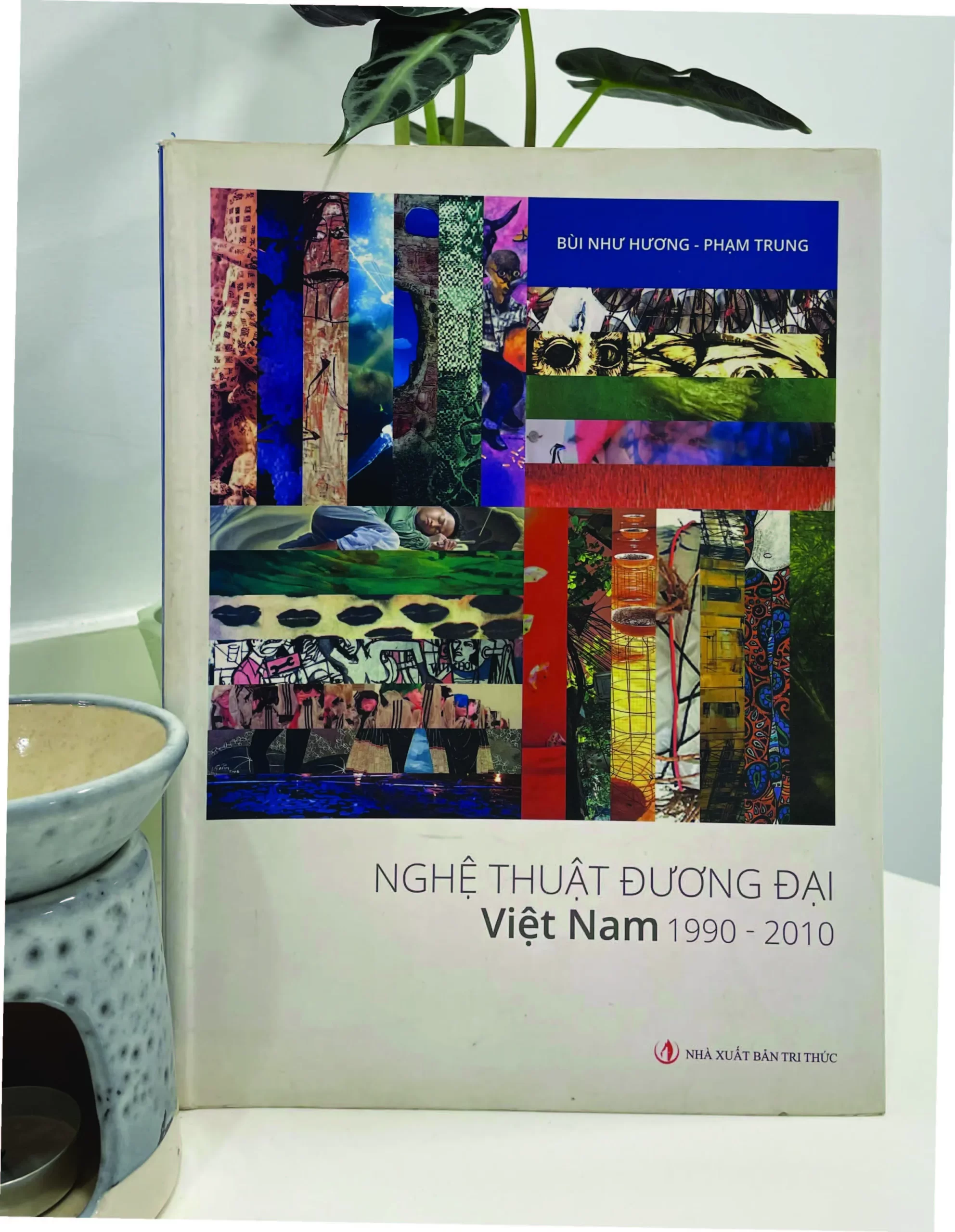

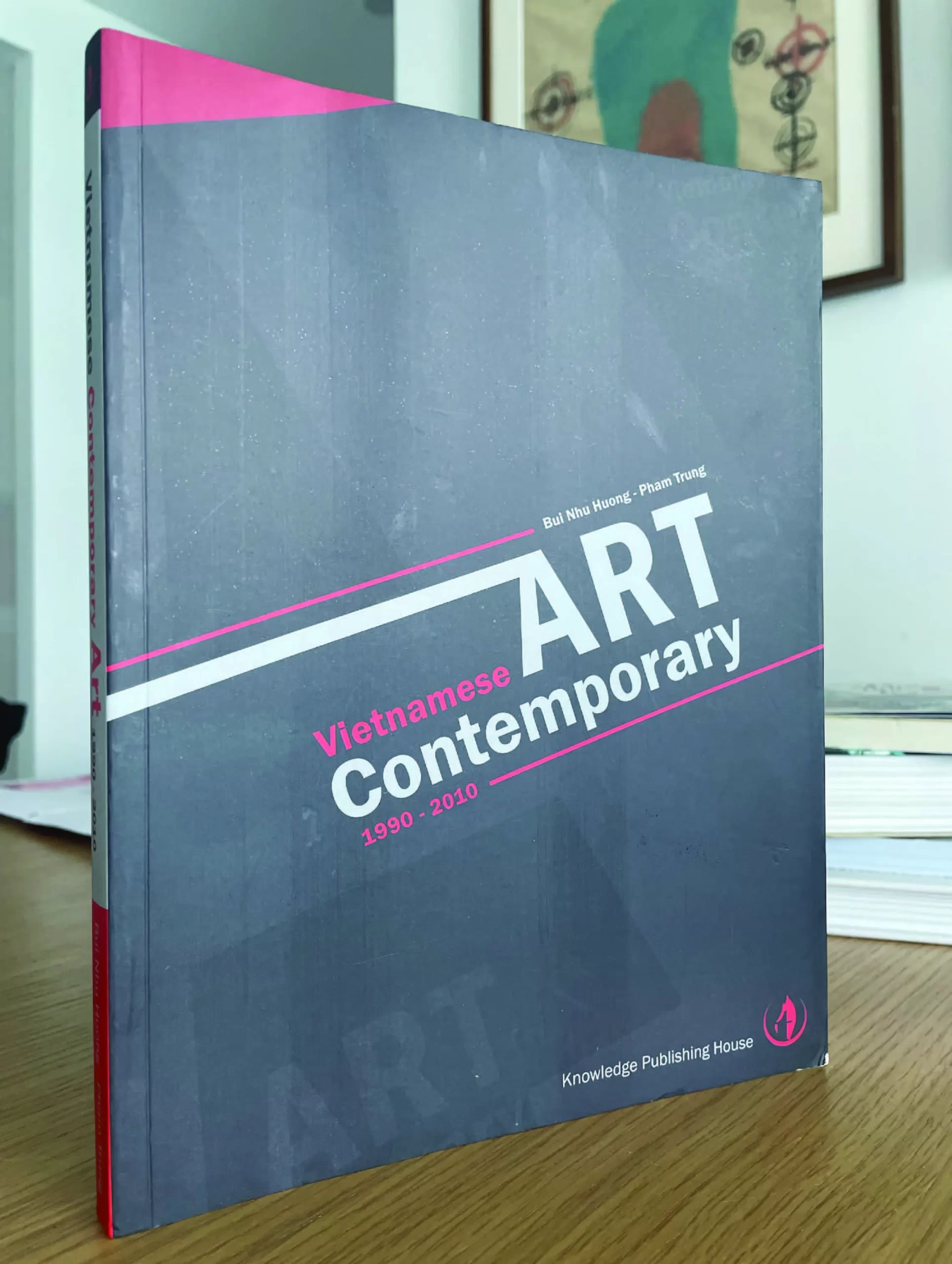

This book was also the premise for the 2012 version that you wrote with Pham Trung, renamed “Vietnamese Contemporary Art 1990-2010”. What factors motivated you to continue writing this 2012 version?

An excellent question. In the 10 years after its conception, after its initial booming period, Vietnam’s “new” painting has somewhat reduced in creativity, replaced by fatigue and boredom, along with widespread commercialization in galleries. Meanwhile, the trend towards forms such as installation, performance, pop art, or video art was quite vibrant, generating great resonance with the emergence of particularly impressive artists and exhibitions. The strength of these art forms lies in their ideas: their social mockery and criticism, coupled with their “not-for-profit” essence and their audience-based interactivity – all through a multimedia lens (sound, light, or visuals).

The book “Vietnamese Contemporary Art 1990-2010” was born in order to more fully depict this period’s art scene. If the first book stops at the first 10 years and leans heavily toward painting, the second book looks forward to the next 10 years with a variety of genres. The artistic criteria of the two books also differ: if book one is focused on an overview with diverse trends, book two introduces some artists’ faces and outstanding works. This is similar to the “Art now” series (Taschen). Of course, every method of making a book is not absolute; it can only address certain criteria of its time.

Did the selection of authors and works in the book under the “contemporary” lens cause certain controversies in the art community at that time?

Most certainly, and I would like to further talk about the word “contemporary” that has long been disputed over, due to a lack of coherence in its understanding. In fact, this word is very open and undefined. For the West, what happens after Modern art, works that adopt an experimental form, perhaps a challenge or an intellectual game, with its artistic validation remaining uncertain, will be grouped under the umbrella term “contemporary art”.

This temporary validation depends on the curators, the media, and the acclaim of forces outside the arts. However, “contemporary” is different from place to place, pertaining to the culture, society, and historical development of art in that place. We cannot apply the model in one place as a standard for another. Specifically, in Vietnam, the development of modern painting and experiments beyond canvas still go hand in hand. Painting and graphics, which are the forte of Vietnamese artists, still give rise to new and contemporary creations in their own way. The word “contemporary” in our second book was considered and chosen in this sense.

As a first-generation critic, would you like to share more about your entrance into this profession and your personal observations about the evolution of art criticism in our country over the past decades? Have you any advice for young people who wish to pursue art criticism?

I have always thought of myself purely as an art lover. Seven years of studying Cybernetics and living in Russia have allowed me to go to museums and learn about world art history. Upon my return, there were opportunities that led me to the Institute of Fine Arts, where I worked from 1983 until retirement.

The state of Vietnam’s art research, in general, is somewhat preliminary, lacking in scientific rigour. In addition to a coherent approach, like other social sciences, this field also requires an aesthetic sensitivity in order to touch and read the language of art. Moreover, they also need to cultivate other interdisciplinary knowledge such as literature, history, archeology, psychology, and languages.

Certain professions choose their followers. Such is art research and criticism, where finding critics is perhaps even more difficult than finding artists. Vietnam is in grave shortage of authentic, effective, and serious critics. The key to art criticism is the parallel of knowledge of art (of humanity in general and of Vietnam in particular) and aesthetic experiences. Furthermore, people who follow this profession also need to have an intellectual personality in its true sense – that is, love of art, love for the profession, and persistence at work. Adding a drop of heavenly luck, and it will surely lead to unexpected fruits of labour.

On behalf of a generation of young researchers, I’d like to thank you for your kind sharing!