Why did you decide to return to Vietnam? What was the contemporary art scene like back then?

I officially settled down in my home country in 1997. In the period of 1993–1997, I was travelling back and forth between the United States and Vietnam. At that time, there wasn’t really a “scene”, as contemporary art did not seem to be present in everyday life.

During my university days in the United States, I was always observing and doing research about Vietnam in an attempt to understand what had caused the war. The war has affected so many Vietnamese lives, including mine. That has been the driving factor behind my art. But in the United States, the war would always be discussed from the American’s point of view. So I came back to Vietnam to collect stories from my home country. That’s my way of conducting research in an unbiased, multi-dimensional manner.

How did the first contemporary artwork you produced in Vietnam come about?

In 1993, I came back to Vietnam to research war photography. During the war, most images that were circulating on international media were by foreign photo-journalists, and as a matter of fact, their viewpoints greatly differed from those of Vietnamese ones.

What struck me the most upon arriving in Vietnam was how at Ben Thanh market there were so many disabled people due to the effects of Agent Orange. A few years later, I made my first work in Vietnam on this topic. In 1998, my work titled “Damaged Gene”, including figurines, dolls, stuffed animals and newborn clothes with conjoined bodies, was launched in Ho Chi Minh City.

I initially wanted to show it at a gallery, but had no connections in the local art world. On the other hand, I wanted the work to reach the wider public. So I rented a booth in a shopping centre to display the work.

“When San Art first started, everything was brand new. The market was still mainly oriented towards paintings…”

Your work must have been quite novel to the Vietnamese general public back then. However, as I know, instead of continuing to have more contemporary art showcases in the country, you spent more time founding San Art. Why so?

In 2003, The Rockefeller Foundation came to see me, asking how they could support the development of contemporary art. I then proposed building a library in Vietnam. Although most Vietnamese artists at the time couldn’t read English, at least they could look at images to have an idea about what was/has been happening in the international art world. The Rockefeller Foundation offered me quite a large amount of money to build this library. However, the grant could not be received by an individual, only organisations were eligible. I tried asking from many parties but was refused by all. I had no choice but to let the opportunity go.

I met and discussed with some friends, sharing our common aspiration to create an art space for the community to come together, exchanging and learning from one another. There, painters/artists would start with contemporary art experiments. And not only that, such a space would also become an institution so that we would be able to officially collaborate with international investment funds. In 2007, we co-founded San Art.

During the course of over 15 years, San Art must have gone through a lot of challenges?

When San Art first started, everything was brand new. The market was still mainly oriented towards paintings, and most Singaporean and Hong Kong collectors favoured post-Indochina style paintings. No one bothered to collect young experimental artists, and galleries did not want to exhibit them because there was no market. If these artists could not sell their works, they would not be able to pay all expenses for the exhibition of such.

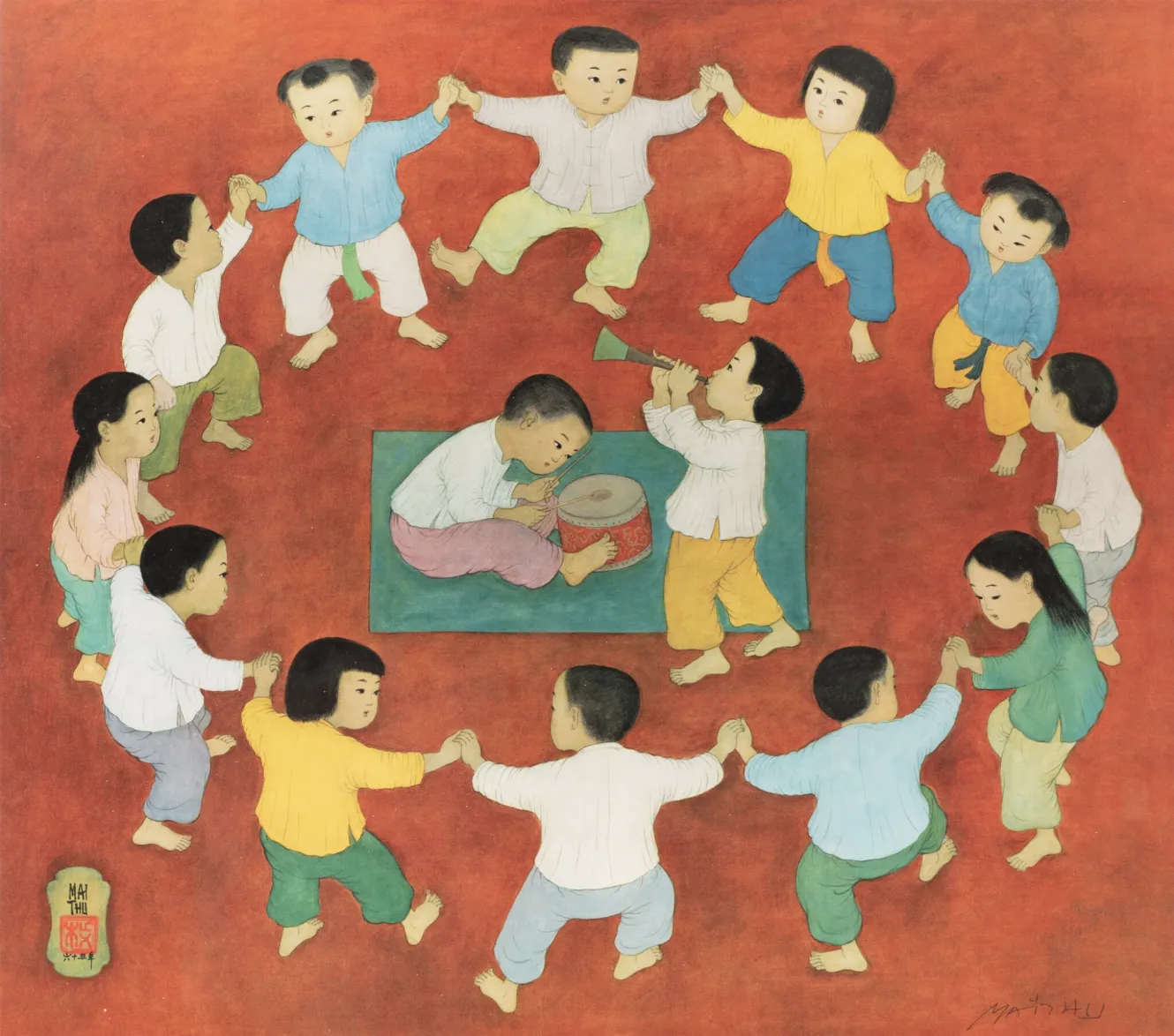

Even until today, the common association with Vietnamese art is still Indochinese paintings. But on a positive note, the surge in prices of paintings by Le Pho and Mai Trung Thu has also helped direct the world’s attention to Vietnam, and then people begin to have a broader view of the Vietnamese art scene. The proof is the increasing number of Vietnamese and international galleries and organisations that have been present in the country, which means the domestic market is emerging. However, despite the difficulties, in the beginning, San Art’s focus was not the public.

What was San Art’s focus then?

San Art focused on people, that is, to train artists. I encouraged artists to conduct research and have well-rounded knowledge of different fields, instead of creating based on techniques or copying reality. Only then would the artist expand the scope of their creation. Once they were able to gain certain achievements, they would return to train and impart knowledge on the next generations.

But commercial activities are still needed for sustainable development, right?

Exactly! Community contribution is a prerequisite, but clearly artists still need to be able to raise a family. San Art also supports artists in introducing their works to collectors. As the artists became more established and San Art’s reputation grew, foreign clients and museums started contacting us to purchase artworks. There have been a few Vietnamese customers but not many. The domestic scene is still not fully open to contemporary art.

What are your thoughts on the market of Vietnamese contemporary art today?

Personally, I see that connections in the market are starting to form, especially the trio of artist-gallery-collector. However, there is an issue that needs to be clarified: there are many artists who sell their works by themselves or collectors who want to cut costs by buying directly from the artists. This will break the operational structure of the art market. As galleries are in charge of promoting artists, they have to invest a lot in their programmes.

For example, San Art does not make its own money. Without collectors who buy works of artists we have introduced, we cannot have the budget for training new artists. Through San Art, artists have a working environment, their works will have a better reach to the world and their commercial value will also increase. Artists would still be able to succeed without us but perhaps it would take longer. Therefore, my wish is that the market will gradually settle down and become stable and transparent in the future.

“As San Art is constantly changing, in the next stage, we want to train the upcoming generation of art managers.“

Can you share the changes that took place through different generations of management at San Art?

Initially, our co-founders included four people. We explored different ways to operate the institution, based on relationships with many organisations and individuals in the visual art field outside of Vietnam and invited them to come and “stir up” the art scene in Ho Chi Minh city. Afterward, when curator Zoe Butt took over the role of the artistic director, the organisation was run a lot more professionally, which led to the emergence of many curators and artists who are solid in their professional expertise.

Things were very difficult when Zoe Butt left. We had to scale back and borrow a space at Ca phe thu Bay (Saturday Coffee Space). To look on the bright side, it was easier to manage and operate a small-scale organisation. But as the next generations enjoy taking on the challenge, we have been able to overcome everything. San Art now is in much better shape.

Currently, San Art managers are young people who have studied abroad or even at San Art. They are continuing what the previous generations have built.

As San Art is constantly changing, in the next stage, we want to train the upcoming generation of art managers. Besides, it is necessary to have diverse programmes to sustain a firm foundation for San Art. Luckily, in every generation, there are people who love art and are willing to contribute with little thought of personal gain. Perhaps they understand our community spirit.

What is your opinion on the new generations of artists?

The new generation of artists at San Art have very different visions to those of established artists when they were at their first steps. Young artists today are unapologetic in their art. From very early on, they already determined that the work did not need a beautiful form, it just needed a strong concept. Perhaps this is thanks to easy access to the world through technology. That means San Art is adapting to the changing social context, focusing on the needs of the upcoming generation. In early 2024, San Art participated in S.E.A. Focus, an art fair in Singapore, focusing on introducing a number of young artists internationally.

Words: Nam Thi

Translation: Hà Đào

Photos: Sàn Art