The title of your show, Thin Space, raises the spectre of ambiguity. You use recurring forms that are ambiguous in their meaning. Could you share with us about how ambiguity operates in your work?

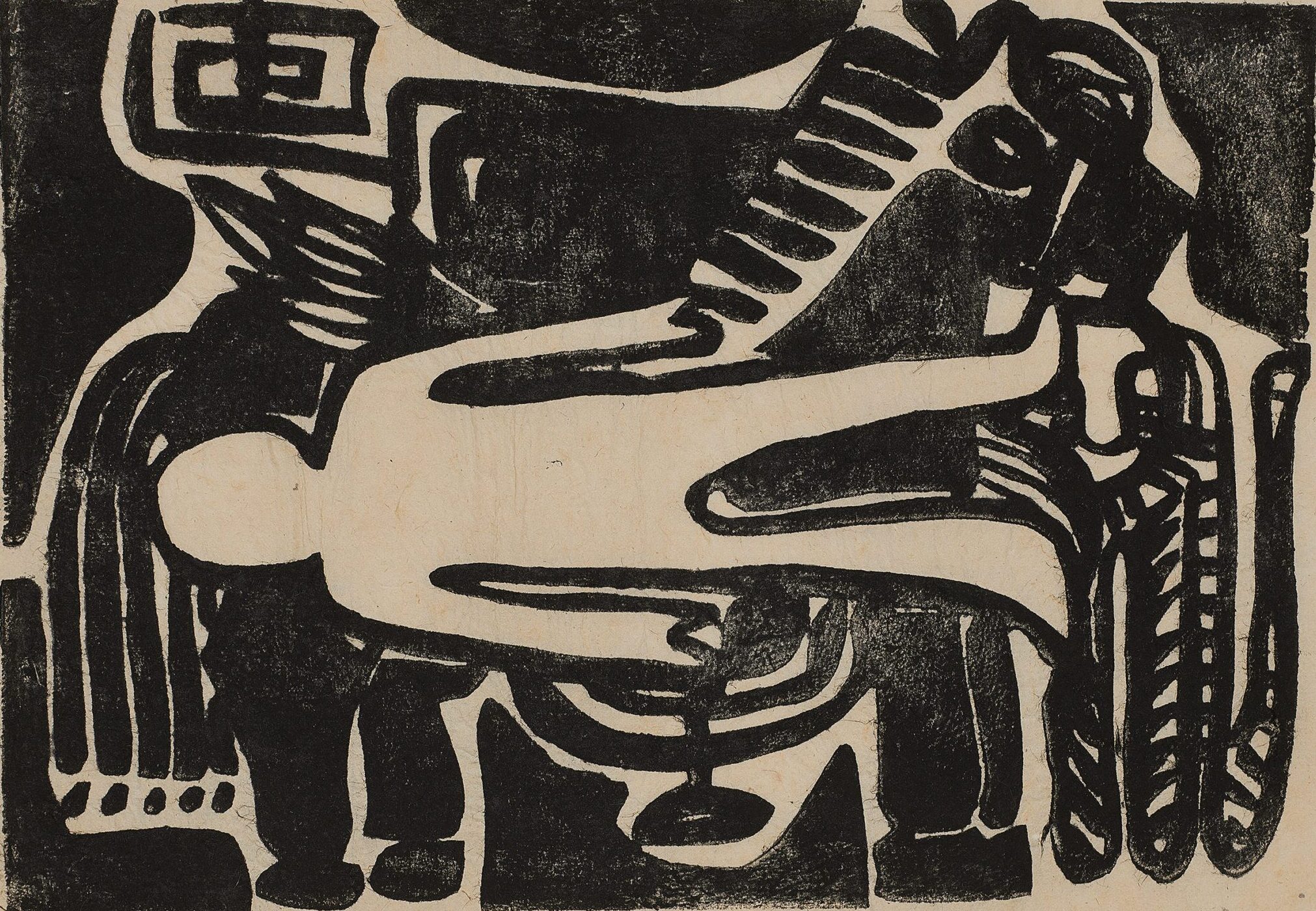

I don’t know if ambiguity is something I set out to elicit intentionally. I think of the forms more as hybrids – things that contain a multitude. Maybe that’s where the ambiguity comes from. From the beginning, I was interested in multiplicity, in ideas of time, how we experience reality, and the overlap between fiction and perception. Science fiction, folklore, mythology – all of that feeds into my work. I was trying to see if it was possible to make a form that both existed and didn’t exist, everywhere and nowhere at the same time.

The form itself came quite naturally. I was drawing, and they started to feel organic but also artificial, like something from deep time, yet simultaneously from the distant future. They don’t belong to a specific place, and I wanted to keep it that way. If a form appears in one landscape and then disappears, it can reconfigure somewhere else, in another material. It’s the same thing, just existing simultaneously in different ways. So the ambiguity comes from that sense of being unfixed and untied to a particular time, environment, or life form.

The flip side of ambiguity might be specificity, but the settings you place these forms into feel deliberately unspecific. You’re pulling images from a wide range of times and locales.

At the beginning, I was working from stock photography, almost like a databank. I started the series [of works on plexiglass] during COVID, which was already a very liminal moment globally. I was collecting these 3D-rendered rooms and generic interior spaces. Those early works were quite liminal. Over time, I started combining many images together, building new landscapes from multiple sources. The more recent works are all composites – collaged constructions made from stock imagery.

There is irony in the title Thin Space since the works feel expansive. It also suggests an in-between condition. Is that accurate?

Yes. It comes from the idea of a “thin place” in Celtic folklore. A thin place is a geographical or temporal point where the distance between our world and the other world is at its smallest. In Wicklow, the town in Ireland where I’m from, there are places people have sought out since the 6th century because they’re believed to be points where the human and non-human worlds intersect. A temporal version of this would be Samhain, which is where Halloween comes from. Outside of these moments or locations, the worlds are said to be three feet apart.

That technical specificity is incredible. It almost sounds like a scientific approach to the supernatural, which makes me think of your father’s work as a ghost hunter.

He never called himself a ghost hunter. He used terms like space clearing or cleansing. It wasn’t religious but related more to folklore. In some ways it’s similar to how ancestral presence is understood in Vietnam, which is widely accepted, without being tied to religious doctrine. He believed that energy or spirits could get trapped in places, and his role was to help clear that. He was also a lifelong folklore collector, recording stories, cures, and local histories.

A lot of the time, his work involved researching the history of a place. Once, when he was helping clear a building, he smelled tar. Later they found out that someone had been tarred there in the 19th century. For him, sensory experience and local history were always connected.

This raises the topic of place and specificity. How has working in Vietnam influenced your practice?

I think it’s made it easier to access a more accepted attitude towards the otherworldly. There’s also a practical side. I really connect with how artists work here – the collaborative nature of the scene, and the impromptu way the spaces operate. Nothing feels fixed. Buildings come and go. Some institutions are designed to exist only temporarily. What lasts are the ideas and the work that happened there.

That sense of flux has definitely shaped how I think about my practice. The idea remains, but it keeps reconfiguring through new spaces, people, and materials. That constant change is something I find exciting.

You’ve shifted towards working with thick acrylic plates, which feel more permanent than the wall-painting works.

I don’t really see them as permanent. Acrylic allows me to “layer time,” quite literally. I take documentation of older, ephemeral works that no longer exist, edit them into new landscapes, and then repaint over them. It’s a way of condensing different timescales.

The material itself is also very reactive. Acrylic changes with light – it absorbs, reflects, and shifts depending on its environment. So even if the work is more conserved, it’s never static. Light, shadow, and surroundings all become part of it. Time and light are active materials.

So the work keeps changing depending on where it’s installed. But at the same time, many of the forms in this exhibition are recycled from earlier works.

Everything contains previous works. Some pieces include years of accumulated material. Recently, I’ve also been making shadows of works that don’t exist yet – creating the shadow first, then later making the form. It reverses the usual process, showing how old work always informs the present.

One notable exception in your practice is the installation Other Mother, which I believe to be the only artwork you’ve ever made that doesn’t include your signature forms per se.

That was my only sculptural installation. I was painting in a landscape surrounded by rubble – broken concrete from demolished buildings. Instead of painting onto the landscape, I took material from it and transformed it. I repainted the concrete with high-gloss enamel so light would remain active. The work existed both inside and outside. Recently, I’ve been thinking about photographing those pieces and reintroducing them into newer works.

There’s a strong sense of recursion in everything you do.

Nothing is ever finished. Everything can become something else. Recently, I discovered that the fabricators I use can chemically strip the prints off the acrylic and the blocks can be reused. What looks permanent usually isn’t.

You also made a wall work in the stairwell at Galerie Quynh, and a facade piece for their anniversary show last year, which is still there at the moment – “permanent” works, until the building gets sold.

Then they will reappear somewhere else, in another form.

Thin Space is on display through 28 February, 2026 at Galerie Quynh, 118 Nguyen Van Thu, Tan Dinh Ward, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Words: David Willis