How did you first come to Vietnam and why did you decide to stay here?

In 1983, the Ministry of Education of the USSR (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) sent me and three other colleagues to Vietnam to establish the Pushkin Institute, a Centre of Russian language and culture. Two months after the arrival, I met Vu Dan Tan and my “double life” began: officially, I was carrying out my mission as an educator and in my spare time, I secretly hung out with artists. Prior to Doi Moi, it was illegal for Vietnamese citizens to have any contacts with foreigners, other than professional ones; the Soviet specialists were highly discouraged to engage with the locals outside the office. However, how could I resist the charms of Vu Dan Tan, the wisdom of Bui Xuan Phai, the humour of Hoang Lap Ngon, and the Quan họ singing by Do Phan? These were my very first encounters with Vietnamese art and culture. After getting married to Vu Dan Tan in 1985, we returned to Russia. In 1990, we decided to come back to Vietnam, which was totally different at that time.

Could you please share the story of Salon Natasha?

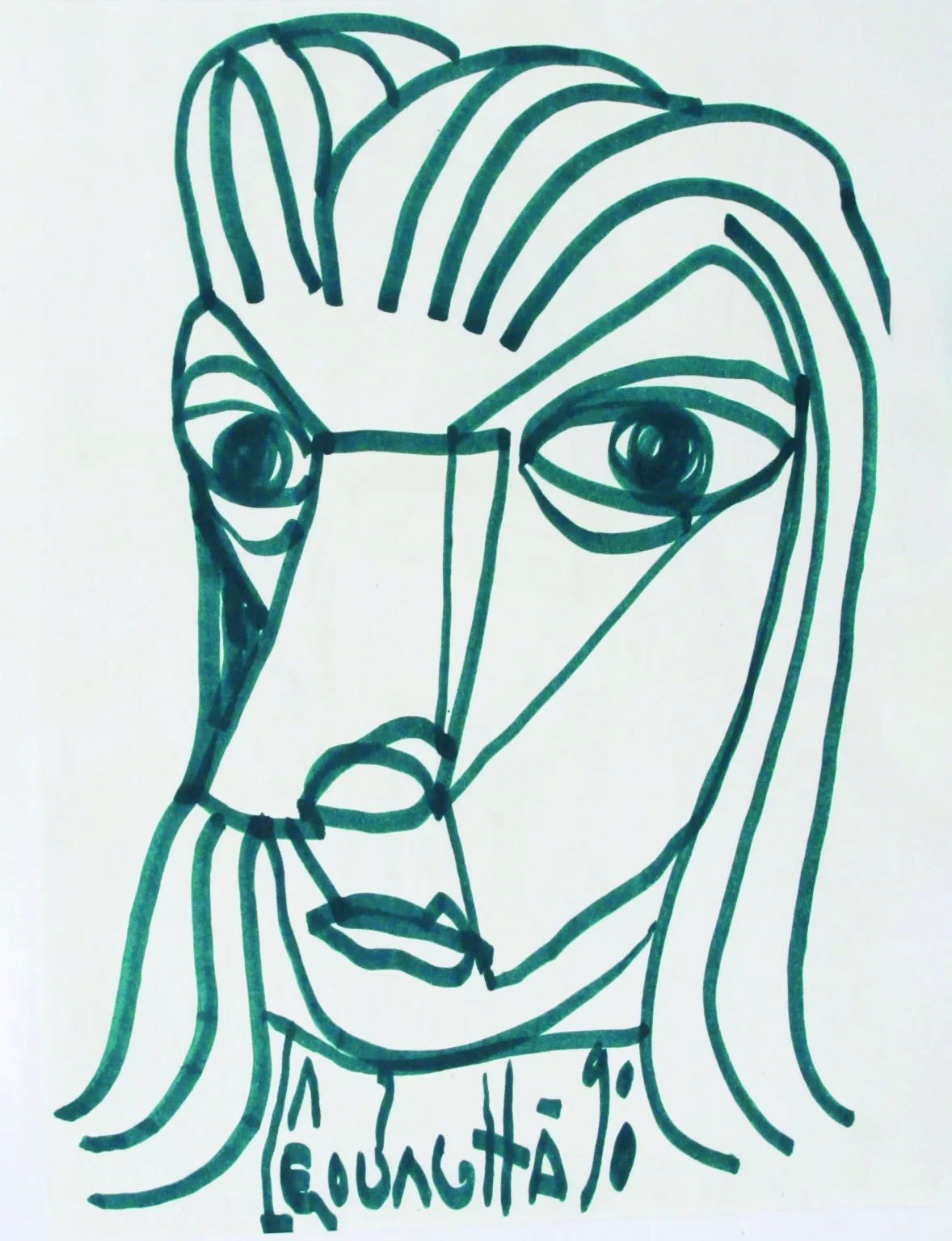

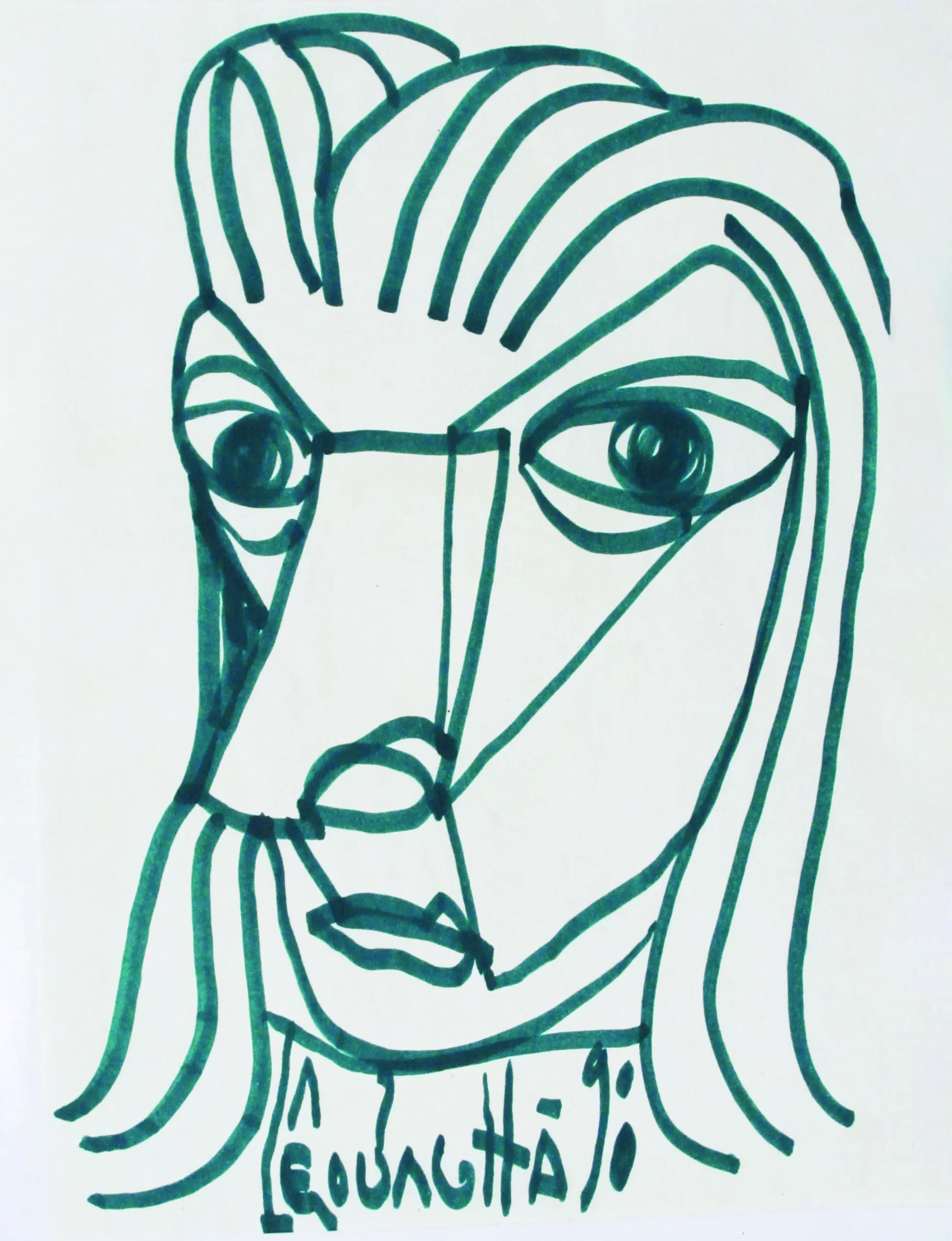

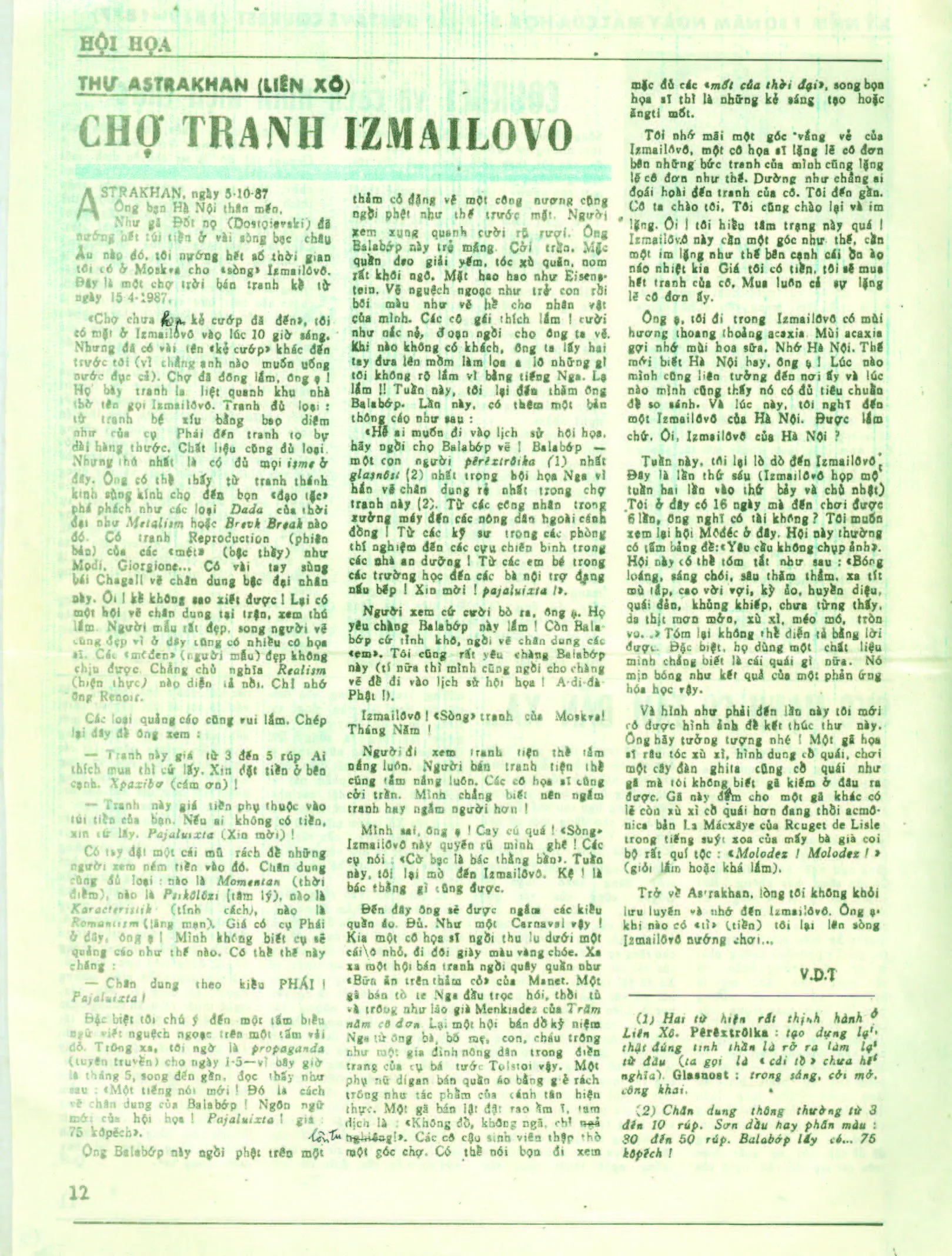

In fact, our return to Vietnam was motivated by the desire to open an art space. It was, without doubt, Tan’s idea. He spent three and a half years with me in Russia (or Soviet Union at the time), and his stay coincided with a tremendous change in all spheres, following the announcement of “perestroika”. Tan was so impressed by a sudden freedom in the sphere of arts: the artists were no longer required to obey the state’s control, to adhere to any official doctrine, or to follow the conventional artistic styles. Furthermore, with its diversity of manifestation and a festive spirit, art began to gain public space in the cities. One can see Tan’s admiration of this liberated, publicly accessible creativity which he witnessed in Izmailovsky Park (Moscow) in his letter to Duong Tuong, published in Sports & Culture (29.11.1987). The artist asked his friend: “Is it possible to have the Izmaylovo of Hanoi?” During a visit to Hanoi in 1989, he discovered that it could not happen – there had been no significant move in the Vietnamese art scene yet. So, his ardent desire to provide a free space, though very tiny, served as an impulse to establish Salon Natasha in 1990.

After getting married to Vu Dan Tan, you continued to work in Vietnam as an art historian and curator. How did you and Tan navigate between professional and personal relationships? Do you think this unique combination is also the soul of Salon Natasha?

For me, the soul of Salon Natasha was Vu Dan Tan. His goal was to create a space for experimental and non-commercial art, free of official intervention. He did not like the concept of it just being a gallery and advocated, instead, for an integration of his studio, our private living area, and the exhibition space. To have daily gatherings of friends, artists, visitors and other creative people in the Salon was his natural way of life. The continuous exchange of ideas was important for him. After the opening of Salon Natasha, Tan was not involved in its management. He chose to remain an artist just like others who were exhibiting here. I was entrusted with this duty. I had the freedom to organise the exhibitions and to work with the artists. The only restriction was that I could not present works that promote violence. Tan’s cousin, Mai Chi Thanh, and Eric Leroux, a French artist, also helped me with the management of the Salon in the 1990s. So Tan and I had separate duties and there were essentially no confrontations regarding the activities of the Salon.

Your book “From Nostalgia towards Explorations: Essays on Contemporary Art in Vietnam” was translated to Vietnamese and published in 2005. At that time, it was almost the first and only publication on Vietnamese modern and contemporary art written by a foreign art historian. How was the reception when it first came out? And how do you situate yourself differently from the local researchers, as well as other foreign researchers on Vietnamese art?

This book is a collection of different essays that were previously published; some of which were published in Vietnam and the others abroad. For me, it was important that Vietnamese people would read it. There were a variety of reactions when the book came out. On the one hand, some people found my judgments too critical. On the other hand, I uploaded some sections of the book on academia.edu, a platform for academic researchers, together with my most critical articles, even those written 20 years ago, and they are all still popular. My perspectives and analysis might differ from those of other art writers, because my background was not art history but linguistics and literary history. I occasionally use methodologies borrowed from these domains, such as semiotics and comparative analysis from linguistics, or sociological examination and psychological inquiry typical for literary criticism. Living in Vietnam, I have the privilege of understanding the local currents better. However, I could never compete with the Vietnamese professionals, who have immersed themselves in the culture’s history of Vietnam.

In 2002, the roundtable “Contemporary Vietnamese art in the international context” took place on Talawas with the participation of Vietnamese and non-Vietnamese from different backgrounds. If we have another roundtable on Vietnamese art now, do you think there would be any difference? How has the art scene shifted over the years?

Each period raises its specific issues, but some questions still remain significant for decades and attract critical thinkers. Sure, it would be beneficial to continue the discussions. However, I would prefer that we have these debates on platforms such as Talawas rather than Facebook. And of course, I think there will be new crucial players: a new generation of young, educated, and dynamic Vietnamese art historians, critics, and curators. My only concern is: would they have the same courageous stand as the previous participants?

Could you share your future plans for Salon Natasha Archive and Vu Dan Tan Art Collection? Do you intend to open a space to continue showcasing these legacies publicly?

Salon Natasha Archive was completed in 2015. It can be accessed online on the website of Asia Art Archive. However, since the collection primarily covers the Salon’s activities, it automatically excludes all works that were created or displayed outside of this context. Vu Dan Tan is introduced in the archive like all other artists collaborating with Salon, so many of his main works – especially the installations he created abroad and his early works – are not included. I am working on the systematising and archiving of his works, but it is a long process. Though I cannot say beforehand when that is going to happen, I hope to open a venue to publicly display these legacies.

Thank you very much!