Can you share with us how you transitioned from a painter at Yet Kieu School (Hanoi Fine Art University) to an experimental artist?

For about 10 years during the Doi Moi period (1986–1996), Vietnam experienced marked changes from economy to culture. The country’s opening allowed an intertwining between East and West, which breathed new life into progressive artists. They realised that art was not limited to classical forms, but founded on creative freedom. The artist was no longer dominated by a particular material; they could transform anything into a medium to convey ideas: from objects, to space, to the body and life itself.

Thanks to this epiphany, the artist began conveying ideas to the audience in a more in-depth and nuanced way. For example, when looking at a painting or statue, your approach to the work is purely visual. But when the work is a video art, you may have to resort to an audio approach; if it is installation art, you can feel it with many senses, even immerse yourself in the work. With performance art, if you understand the artist’s ideas, you can improvise, co-perform, or dialogue. It is the freedom and creativity contained in these art forms that pull me toward them.

In the interview “Right People, Wrong Timing” by Green Papaya about independent art spaces in Southeast Asia, you shared that Vietnamese contemporary art in the 90s – early 2000s remained largely ‘underground’, with next to no support. Yet, you also commented that such a period was unique and generated a lot of creative inspiration for artists. Can you explain why?

The contemporary art environment at that time was rudimentary and lacking in many aspects. Artists only had basic training from school, no art direction, much less knowledge about new art trends in the world. The art funding system was almost nonexistent or limited to academic activities. Exhibition space was also a big concern. Most contemporary exhibitions then could only be hosted in private homes or studios of artists and their friends, with a few rare venues being Salon Natasha, the Goethe-Institut, and L’Espace.

The exhibitions at that time were of a local nature and took place on a small scale. In 1999, Nha San Studio, co-founded by artists Nguyen Manh Duc and Tran Luong, brought together many domestic and foreign contemporary artists, creating a vibrant atmosphere with many far-renowned works. Perhaps that shared hardship has retained artists’ purity and openness; it made them more willing to exchange knowledge, share experiences, and support one another – resulting in a harmonious atmosphere, filled with creative energy.

In 2003, in the landmark group exhibition “Green Red Yellow” conducted by curator Tran Luong, there was one work of yours that still leaves a mark in the Hanoi art community, which is “Sleepwalk” (2003). Can you share your thoughts on this piece?

After Doi Moi, big cities began to develop in flux, creating a chasm between urban and rural. This drew a large community of working-class laborers in the countryside to the city, looking to make a living. Their lives are precarious due to the lack of a stable job, and they even become the subject of persecution or discrimination. Their bewildered and quiet faces behind hidden corners made me curious: Why did they leave their homeland to go to a place where they were looked down upon?

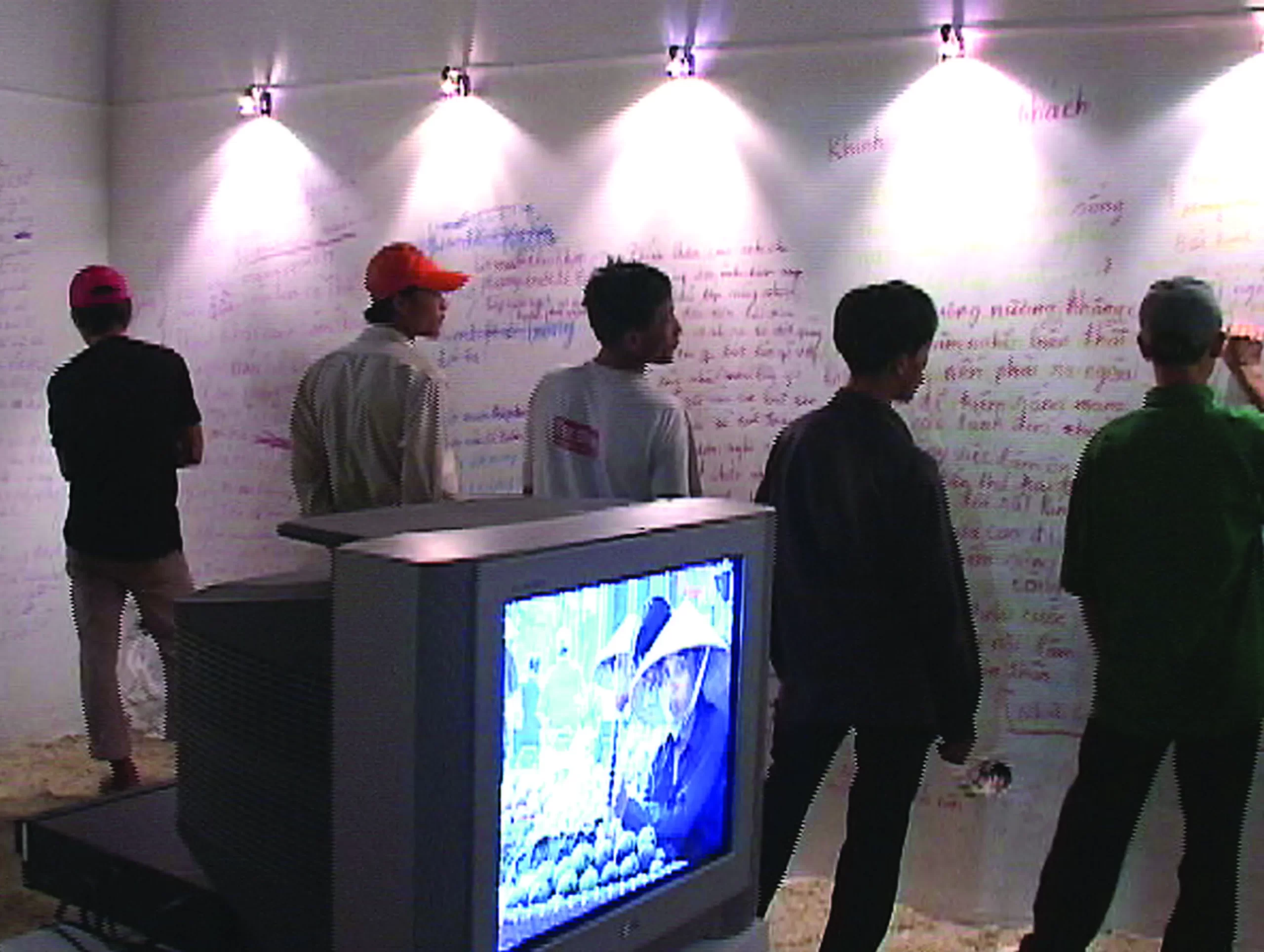

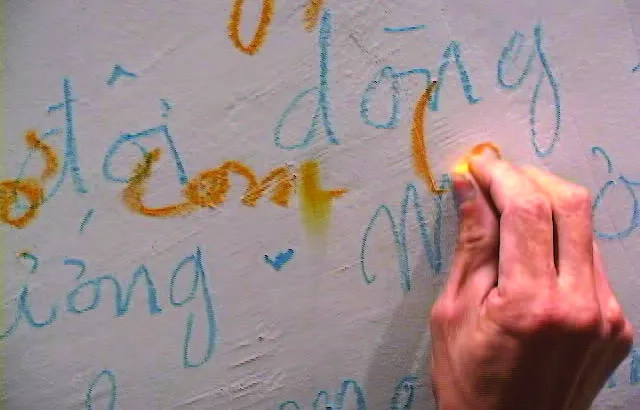

In 2002, I was making documentaries about migrants in Hanoi when I was invited by Tran Luong to participate in the “Green Red Yellow” Exhibition. I decided to accept, because this is an opportunity for migrants to say what they want to say, and at the same time erase the prejudices of city residents towards migrants. Through conversations with the audience, I hoped to use art to bring people closer together, and fortunately the work was far more successful than expected.

After founding Ryllega Gallery, you also played the role of an art organiser and curator. How do you see the relationship between artists and curators in the Vietnamese context at that time?

At that time, there was no professional curator in Vietnam. Therefore, some artists had to take on this responsibility, starting with small-scale exhibitions. When local artists stood in as curators, they possessed many advantages, including their understanding of the Vietnamese context, including human culture and society in each region. These “curators’’ also forged a close relationship with artists and the local art scene.

However, such a method of organising was not without its limitations: scarce budget, closeness in thinking, personal biases, and limited resources, which somewhat chipped away the artists’ freedom.

Why did you decide to close Ryllega and subsequently detached yourself from contemporary art after that?

Ryllega Gallery is a non-profit project to support artists practicing contemporary art. The operating expenses were mainly from me and, after one year of operation, a partial support from Dong Son Today fund. By the end of 2008, when the world economy began to sink into crisis, the two largest large art sponsors, Dong Son Today and Ford, withdrew from Vietnam. I myself could not continue to maintain Ryllega anymore.

At that time, I changed the Ryllega Gallery to a moving art space, but also could only add one more event, the Ryllega Berlin, co-organised by Veronika Radulovic. I think this is only natural, life is filled with ups and downs; Art is always influenced by many things such as circumstances, time, space, people, etc. Perhaps that is the most natural course of development. Looking at the cultural and artistic history of other countries, I can deduce a similar process.

Thank you for your kind sharing!