The histories of postcolonial and postwar migration is not new to Vietnam or the Caribbean. What remains unresolved are the identities shaped from its aftermath: children born into, or displaced toward, lands far from their parents’ origins.

Archive / Post–Archive at VCCA, part of Photo Hanoi ‘25 orbits around the aftermath of post-colonial trauma, and wonder whether we can fully shed its legacies. Through the lenses of migration and adaptation, the exhibition questions how diasporic identities are constructed through the works of 15 artists across the Vietnamese diaspora and Caribbean artists. The exhibition asks: how do those who inherit displacement learn to imagine or make sense of a motherland?

Held in one of the largest exhibition spaces in Vietnam, Archive / Post–Archive is ambitious in its scope. As a result, there ends up a tension between the viewing experience and the intended narration. As curators Éline Gourgues and Do Tuong Linh note, the exhibition seeks to “establish connections with Vietnamese and Caribbean artists who share similar concerns” on identity born out of displacement. But the exhibition layout opens in two directions, juxtaposing two narrative lines: the left side concentrates works by Caribbean artists (Sylvie Bonnot, Claire Zaniolo, Emeline Ametis, Nathyfa Michel, Adeline Rapon, Kosisochukwu Nnebe, Manon Ficuciello, Laila Hida), while the right side is devoted primarily to Vietnamese artists (Flora Mae Nguyen, Dinh Q Le, Prune Phi, Le Nguyen Phuong, Quang Lam, Sol Kim). Of course, the arrangement also depends on the scale and dimensions of the works, but it nonetheless means that viewers are compelled to choose one direction and encounter one side of the story first. This layout creates an intriguing visual rhythm, yet it also means the two narrative lines move on almost parallel tracks, crossing only intermittently before drifting apart again. Perhaps this reflects a universal condition: even when we appear to share a common experience, the stories each of us carries, and the ways we interpret them, can never fully align. And precisely through this spatial organisation, the exhibition unfolds into a more layered narrative – a wider panorama of how identity takes shape within the Vietnamese and Caribbean diasporic communities. Archive / Post–Archive positions itself as an act to “challenge official histories and reveal fragments of lived experience, myths, and counter-narratives that complicate our understanding of contemporary society.” More specifically, the exhibition’s curatorial flow places viewers in the position of the artists themselves, guiding them through a journey of making sense of identity from afar, traced across three stages: revisiting recorded histories, filling in the gaps through imagination, and returning to the most immediate point of connection – family.

Similar to the act of tracing history and memory, one often begins with what has been recorded. In Flora Mae Nguyen’s Love Me Tender, the opening work of the exhibition, a work stitched from multiple archives: family albums, state documents, institutional images, antique postcards – torn, cyanotyped, overpainted and redrawn. At the same time, Adeline Rapon’s Not So Bad Our Little Creole, Is It?, recreates images of Black West Indian women found on colonial postcards once held by foreign collectors.Rapon’s artistic protocol unfolds in three movements: the acquisition of colonial postcards – removing them from an exoticising commodity circuit; an embodied subversion, as she restages their poses using her own body; and a visual disruption through the introduction of contemporary elements of confinement. Together, these two works sketch out the core argument of the exhibition: photography was once a tool of documentation, and has since evolved into a counter-narrative to official histories. Their acts of deconstruction and reappropriation probe the indexical authority of the photographic image, reframing the colonial gaze while offering the possibility of repair.

Displacement also forces one to rely on the imagination of the motherland, filling gaps carved out by distance. In Emeline Ametis’s Péyi Manman (Mothers’ Country), observers are offered a seashell laid still, white bubbling waves, and a sunlit body against oceanic blue. All the elements suggest a beachscape, idyllic. Here, photography becomes a tool for constructing a reality: her mother’s native archipelago, once marked by violence, appears instead as a mere postcard landscape, a vacation destination. Meanwhile, Quang Lam’s Tales From The Dragon Land turns to Vietnam’s own myth of origins to make sense of its long histories of migration – the story of Lac Long Quan and the Au Co, whose hundred children would one day scatter between the mountains and the sea. Through the “fruits of the dragons,” their trajectories appear scattered, dispersed across locations, surfaces, and shifting contexts – a lineage continually carried elsewhere.

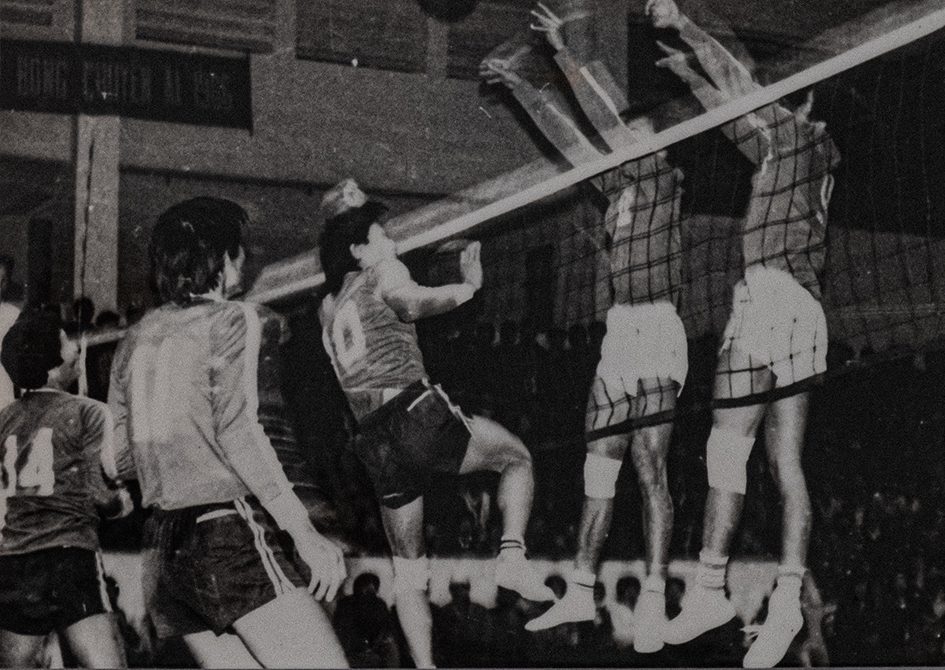

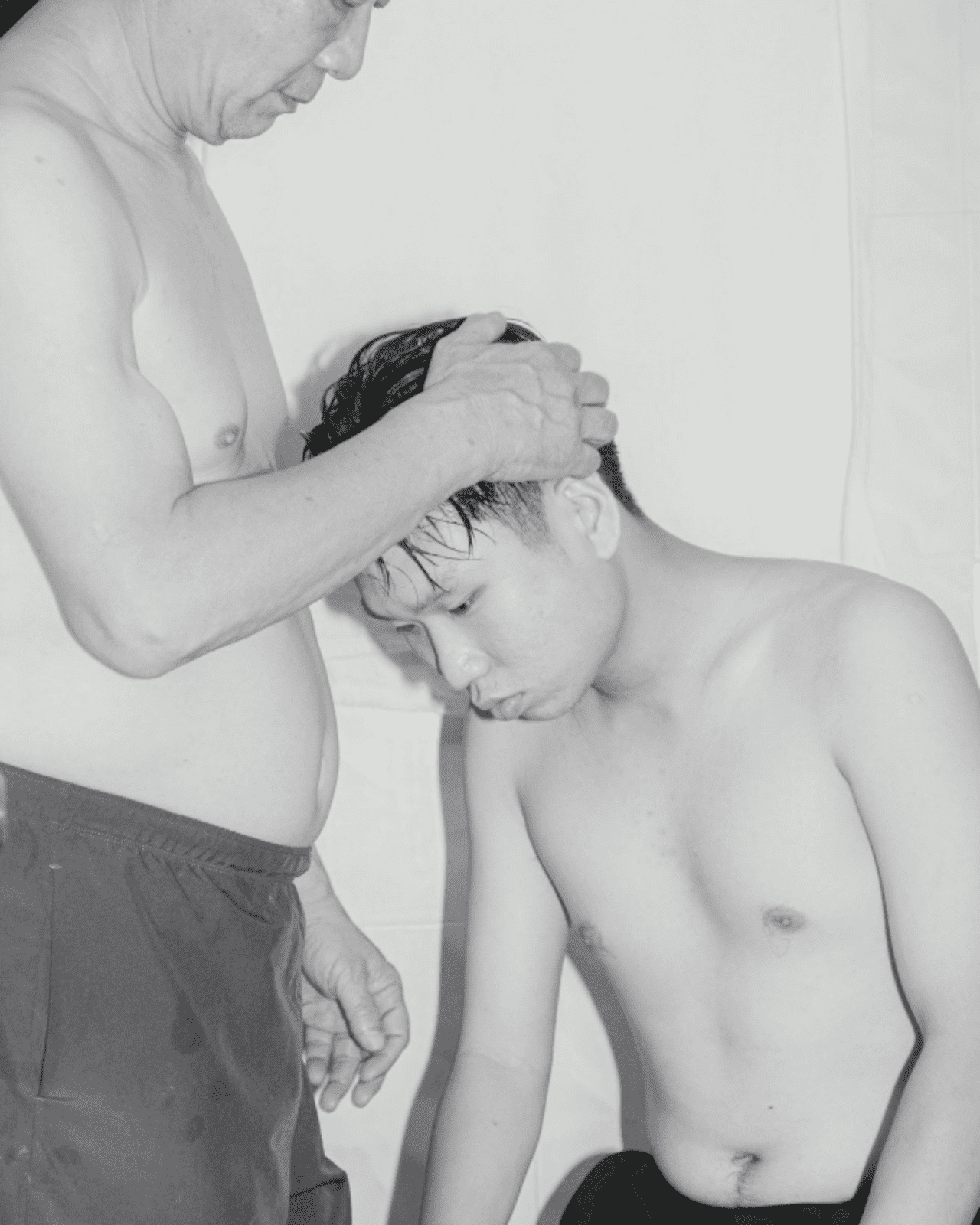

Most of the works in the exhibition deal with the past, yet its most tender piece suggests that even in moments of oblivion, we find ways to reconnect. Le Nguyen Phuong’s The Meeting Place unfolds as a two-sided photographic installation. One side comprises archival images from his family albums: his father, then a professional volleyball player under the Hanoi Military command and a member of Vietnam’s national team, captured during a training trip to Siem Reap. The other presents photographs taken in 2024, when Le invited his father to return to Siem Reap nearly thirty years after his first visit. The gesture becomes a quiet act of retrieval, allowing his father to revisit personal memories and reflect on a formative chapter in their family history. Within the broader concerns of the exhibition, the series reveals the often unseen layers of history that reside within familial and personal relationships.

The issues surrounding immigrants are intensely gazed upon across developing nations today, including within Vietnamese and Caribbean communities, as millions now live far from their motherlands. But while Archive / Post–Archive lingers on difficult truths: post-colonial trauma, displacement, and the oblivion of disconnection; it is also defiant, warm and unexpectedly soothing. It looks at colonialism and its aftermath, while acknowledging our yearning for connection and sense of belonging. Perhaps the question is not how much we continue to suffer from inherited traumas, but how we learn to be at ease with where we are, to reconcile, and to understand that history is not only inherited, but continually rewritten.

Words: Kieu-Nga Trang