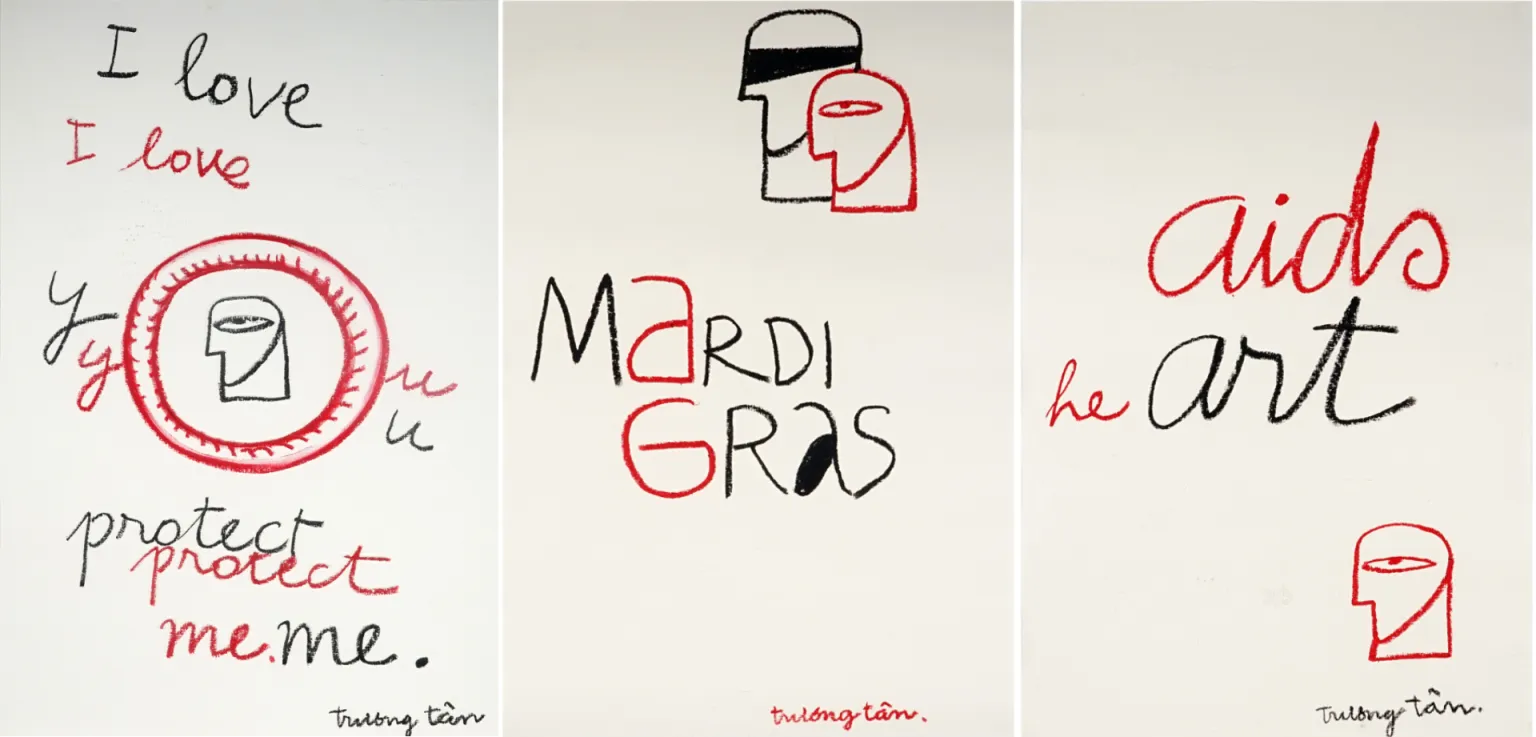

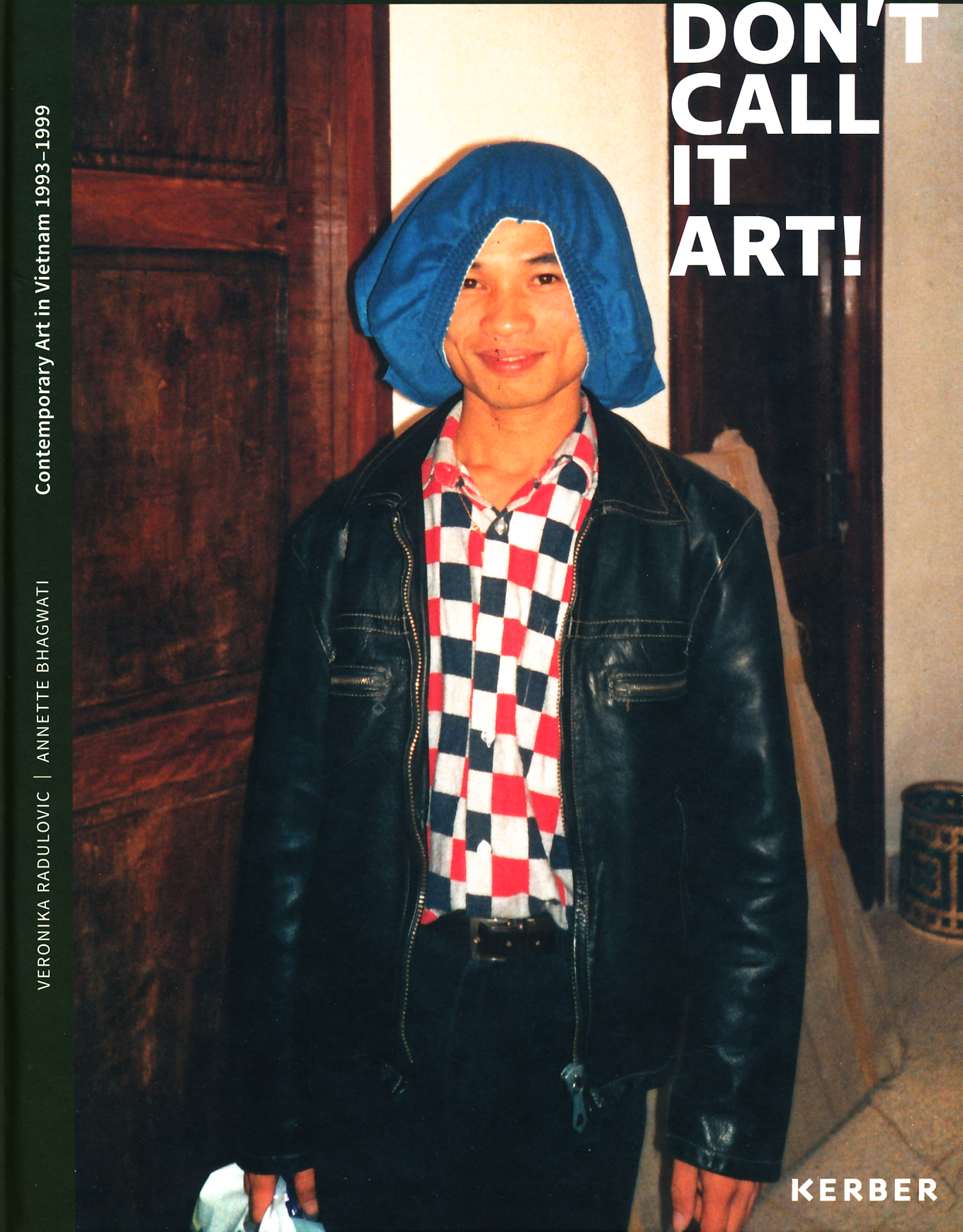

During the 90s, Truong Tan was a Vietnamese artist featured in Western media with the densest frequency. However, both the media and commercial actors seem to have deliberately tagged the name “Truong Tan” to a series of labels such as “gay”, “censorship”, “Western boyrfriend”. A specific example is Tim Larimer’s 1995 article in the Washington Post. Some researchers also mistakenly assumed that you are an artist representing and fighting for the gay community? The fact that you were Vietnam’s first openly gay artist does not equate to such induction.

Not only then, but even now still. However, I’ve always thought that if my works are not quite like that, then I am not afraid. In 1994, Jeffrey Hantover messaged me to ask if his writing about me was okay. I clarified to him that it was his business, even if he used all the wrong phrases. I am an artist and should only be responsible for my work, and he should be responsible for his. Back in 1995 when my artworks at Red River Gallery were censored, a police officer asked me why I let them write such disturbing articles about me. I did tell him that it was their responsibility, not mine. All of my artworks could easily be seen here, totally different from the way they wrote about them. I think readers should also be responsible for the information they consume. My works refer to humans in general, not any specific individual. Humans, regardless of sexual orientation, are human, and were born this way. If we keep fighting, it means we still see ourselves as the underdog. I don’t have the energy for that. If we still distinguish and label ourselves as homosexuals, we will be discriminated against forever. Let’s just treat each other as human beings, that’s that.

From the very beginning, you have been searching for ways to free yourself of classical conventions.

Back then, most artists made the same art, with the same old subjects: birds, flowers, fish, ladies. There was only our group who painted on dó paper in a completely different style, without any formality. I have always wondered why artists limited themselves to such cliche concepts and still constantly clinged onto rigid theoretical techniques like lighting and shading – just like a novice? In 1992, in an exhibition at Vietnam University of Fine Arts, I displayed two artworks named “Mirror” and “Circus” with mixed materials: oil, canvas, and also needles, hair, vaseline, empty bottles, and mirror shards, etc. It was the first time such unusual works appeared at a university exhibition, so everyone was talking about them. Even before graduation, I had made art differently. As early as 1987, I tried to sketch the concepts popping in my head, like the series with legs on the wall. I was later told that my style was similar to Louise Bourgeois’, but honestly, I didn’t know who she was. I still keep those sketches. Then people compared my works with Keith Haring and many others, but it was my own language, one I invented before hearing of them.

You were the valedictorian at graduation, and were retained as a lecturer until 1997 when you moved to France. Your classroom had a thoroughly different vibe from traditional ones. Thus, your students like Nguyen Minh Thanh, Nguyen Van Cuong, Nguyen Quang Huy… could gather enough confidence to produce work with you as fellow colleagues.

I think I am lucky to possess no jealousy – isn’t that good! I always told my students that I was not here to lecture, but to help them improve and enhance what they already had and see it more clearly. And should they get better, they would need to pay it forward. To me, classroom lecturers are not necessarily our teachers. Our teachers should be the masters found in art books. That’s why when in college, I was told that my works embodied Western vibes, not Vietnamese. And when I made Vietnamese style works, they were graded 9/10, but my Western style ones only got 8/10.

Minh Thanh and you were the first ones to collectively translate the terms “performance art” and “installation art” into Vietnamese.

That’s true. Some said that “installation art” was already translated prior to that in Saigon, but what good is a translated term without context and practical examples to illustrate it? Others proclaimed, ah, then those displayed in templates and pagodas are also installation art. Such interpretations were completely wrong, thanks to the disregard for vigorous research and the lazy habit of assuming similar things to be the same. It was neither thorough nor complete.

On “performance art”, we agreed to translate it to “nghệ thuật trình diễn”, not “trình diễn” (performance) or “trình diễn nghệ thuật” (art performance). “Art performance” actually has been in existence for a while, like drama performances on the theater stage. However, “performance art” is a conceptual art that uses one’s body to interpret and cannot be shown in any other way than performing. Even many practitioners are still confused about this: a work that is just like a play can’t be called performance art. And at that time, many people who didn’t understand it started to dance randomly – like in spirit conjuring sessions – and called it “contemporary dance”, but it’s not any close to performance art!

You were the first Vietnamese artist to produce a performance artwork.

My earliest premise for performance art that I could recall was one in January 1994, when I wrapped cloth around myself and then broke free. It was not a complete work but did carry the vibes of performance art. It was so easy for me to get into this discipline because I loved dancing when I was a kid. At 12, I suddenly noticed that my body was nice looking, then subsequently applied to a dance school. But I got rejected because I was too petite. For the graduation exam, I picked a topic about dancing, but it was extremely challenging to get a permit from the Ministry of Culture to enter a dance school, besides other documents. Later on, I found myself enchanted by performance art, often performed at my friends’ exhibitions. Instead of doing it on the opening day, I preferred the closing day so that people could have a chance to gather again in a cozy and joyful ambiance. I was keen on performance art so I did quite a lot of it. I think I was born to do performance art.

It’s always a pleasure talking to you, and see you in Hanoi after the pandemic!

Words: Ace Le

(This article was first published in Art Republik #4.)